User:WezSchultz/西藏 (1912–1951)

བོད་ Bod 西藏 | |

|---|---|

.mw-parser-output .infobox-subbox{padding:0;border:none;margin:-3px;width:auto;min-width:100%;font-size:100%;clear:none;float:none;background-color:transparent}.mw-parser-output .infobox-3cols-child{margin:auto}.mw-parser-output .infobox .navbar{font-size:100%}body.skin-minerva .mw-parser-output .infobox-header,body.skin-minerva .mw-parser-output .infobox-subheader,body.skin-minerva .mw-parser-output .infobox-above,body.skin-minerva .mw-parser-output .infobox-title,body.skin-minerva .mw-parser-output .infobox-image,body.skin-minerva .mw-parser-output .infobox-full-data,body.skin-minerva .mw-parser-output .infobox-below{text-align:center}西藏

从 1912年清朝垮台至1951年中华人民共和国吞并西藏之间,西藏是一个事实上的独立国家[1]

西藏甘丹颇章政权是清朝的保护国[2] [3] [4] [5]直到1912年。 [6] [7]中华民国临时政府接替清朝为中华政府时,与清政府签订条约,将皇权的全部领土继承为新的共和国。 然而,它无法在西藏维护任何权威。达赖喇嘛宣布西藏与中国的关系随着清朝的垮台而结束并宣布独立。西藏和蒙古还签署了一项条约,宣布相互承认从中国独立。 [8]西藏在这一时期宣布独立并处理自己的内政和对外事务,尽管其独立性并未得到任何西方大国的正式承认[1],根据国际法,西藏被视为“事实上的独立国家”。[9]

1931年和1946年,西藏政府再次派使者到中国国民议会讨论西藏的地位,但他们两手空空地回来了。 [10][需要引文]

1933 年十三世达赖喇嘛逝世后,国民政府派往拉萨展开西藏地位谈判的慰问团获准开设办事处并留在那里,尽管没有达成任何协议。 [11]

国民党领导的中华民国政府在反共内战中战败,1950年中国人民解放军进入西藏,次年与中国签订十七条协议,重申中国对西藏的主权。

历史

[编辑]清朝灭亡(1911-1912)

[编辑]

清朝驱逐准噶尔汗国后,西藏于1720年归中国清朝统治。但到了 19 世纪末,中国在西藏的权威不过是象征性的。 [12] 1911年至1912年辛亥革命后,西藏民兵在辛亥拉萨动乱后对驻扎在西藏的清军发动突然袭击。 1912年清朝灭亡后,在拉萨的清官被迫签订“三点协议”,清军在西藏中部投降和驱逐。 1912年初,中华民国北洋政府取代清朝成为中国政府,新的共和国宣布对前朝的所有领土拥有主权,其中包括中国22个省、西藏和外蒙古。 [13]这一主张在太后隆宇代六岁宣统帝签署的《清帝退位诏书》中有规定:“…… 满、汉、蒙、回、藏五族的领土继续保持领土完整,成为一个伟大的中华民国”(. . . 仍合滿、漢、蒙、回、藏五族完全領土,為一大中華民國)。 [14] [15] [16] 1912年通过的中华民国临时宪法明确规定,包括西藏在内的新共和国边疆地区为国家的组成部分。 [17]

新共和国成立后,中国临时大总统袁世凯致电十三世达赖喇嘛,恢复他先前的头衔。达赖喇嘛拒绝接受这些头衔,回答说他“打算在西藏实行世俗统治和教会统治”。 [18] 1913年,清朝在1910年派遣军事远征建立中国对西藏的直接统治时逃往印度的达赖喇嘛[19]返回拉萨并发表宣言,声明中国与西藏的关系皇帝和西藏“一直是守护神和神父的关系,没有建立在从属于另一个的基础上”。公告称:“我们是一个宗教信仰独立的小国。” [20] [21]

在1913年1月,阿旺·洛桑·德爾智和其他三名藏族代表[22]在库伦签署了西藏和蒙古条约,宣布相互承认主权和双方独立自中国。英国外交官查尔斯·贝尔写道,十三世达赖喇嘛告诉他,他没有授权阿旺·洛桑·德爾智代表西藏缔结任何条约。 [23] [24]因为文本没有刊登,一些人起初怀疑条约的存在, [25]但蒙古文本是1982年由蒙古科学院刊登[22] [26][需要引文]

西姆拉公约 (1914)

[编辑]1913-1914年,英国、西藏和中华民国在西姆拉举行会议。英国建议将藏区划分为外藏区和内藏区(仿照早先中俄就蒙古问题达成的协议)。外藏,与现代西藏自治区大致相同的区域,将在中国宗主权下自治。在这方面,中国会避免“干涉行政”。在由东部康区和安多组成的内藏,拉萨将只保留对宗教事务的控制权。 [27]从1908年到1918年,康区有中国驻军,地方诸侯隶属于其指挥官。

当关于西藏内外具体边界的谈判破裂时,英国首席谈判代表亨利·麥克馬洪划出了众所周知的麦克马洪线划定了西藏-印度边界,相当于英国吞并了9000平方公里的西藏传统领土在西藏南部,即达旺区,对应现代印度阿鲁纳恰尔邦的西北端,同时承认中国对西藏的宗主权[28]并确认后者作为中国领土的一部分的地位,中国政府并承诺西藏不会成为中国的一个省份。 [29] [10]

后来中国政府声称这条麦克马洪线非法转让了大量领土给印度。有争议的领土被印度称为阿鲁纳恰尔邦,中国称为藏南。 1912 年,当时英国已经与当地部落首领签订了协议,并设立了东北边疆区来管理该地区。

《西姆拉公约》由三个代表团共同草签,但由于对外藏和内藏之间的边界划分方式不满,北京立即拒绝了。亨利·麥克馬洪和西藏人随后签署了作为双边协议的文件,并附有一份说明,否认中国享有其中规定的任何权利,除非签署。英国管理的印度政府最初拒绝了麦克马洪的双边协议,因为它与1907年的英俄公约不符。 [10] [30]

麦克马洪线被英国和后来的独立印度政府视为边界。然而,此后中国的观点一直认为,由于声称对西藏拥有主权的中国没有签署该条约,该条约毫无意义,印度对阿鲁纳恰尔邦部分地区的吞并和控制是非法的。 (这为 1962 年的中印战争以及今天持续存在的中印边界争端铺平了道路。 )

1938 年,英国最终公布了作为双边协议的西姆拉公约,并要求位于麦克马洪线以南的达旺寺停止向拉萨纳税。林孝庭声称从图书馆召回了一卷 CU Aitchison 的《条约集》 ,最初出版时附有说明未在西姆拉达成具有约束力的协议的说明, [31] 并替换为新卷,该卷的出版日期为 1929 年,其中包括 Simla 和编辑说明,其中指出西藏和英国,而不是中国,接受该协议具有约束力。

1907 年的英俄条约早先引起英国人质疑西姆拉的有效性,但 1917 年被俄罗斯人放弃,1921 年被俄罗斯人和英国人联合放弃。 [32]然而,西藏在 1940 年代改变了它在麦克马洪线上的位置。 1947 年底,西藏政府写了一份照会提交给新独立的印度外交部,声称对麦克马洪线以南的藏区拥有主权。 [33]此外,由于拒绝签署西姆拉文件,中国政府逃脱了对麦克马洪线有效性的任何承认。 [33]

1933年十三世达赖喇嘛逝世后

[编辑]

由于驱逐驻藏大臣从西藏于1912年,西藏和中国之间的通信发生了仅与英国调解人。 [21] 1933年12月十三世达赖喇嘛逝世后,直接通讯恢复, [21]中国向拉萨派出了以黄木松将军为首的“慰问团”。 [34]

据一些记载,十三世达赖喇嘛去世后不久,噶厦重申了其 1914 年的立场,即西藏名义上仍是中国的一部分,前提是西藏可以管理自己的政治事务。 [35] [36] SL Kuzmin在达兰萨拉西藏文献档案馆发表的文章《隐藏的西藏:独立和占领的历史》中引用了几个消息来源,表明西藏政府没有宣布西藏成为中国的一部分,尽管西藏政府暗示中国拥有主权。国民党政府。 [37]自1912年以来,西藏实际上不受中国控制,但在其他场合,它表示愿意接受名义上的从属地位作为中国的一部分,前提是西藏内部制度不受影响,并让中国放弃对一些重要地区的控制。康区和安多的藏族地区。 [10]为了支持中国对西藏的统治没有中断的说法,中国辩称,官方文件显示中国国民大会和议会两院都有藏族成员,他们的名字一直被保留下来。 [38]

中国随后获准在拉萨设立办事处,由蒙藏委员会负责人,并由蒙藏委員會事务主任吴忠信(吴忠信)领导, [21]来自中国的消息称其为行政机关,[38] ——但藏人声称他们拒绝了关于西藏应该成为中国一部分的中方提议,并反过来要求归还德里楚(长江)领土。 [21]针对中国在拉萨设立办事处,英国人也获得了类似的允许,并在那里设立了自己的办事处。 [21]

1934年,由潘达斯坦托格比和潘达仓拉嘎领导的康巴叛乱爆发,反对西藏政府,潘达仓家族率领康巴部落反对西藏军队。

1930年至1949 年

[编辑]

1935年,拉姆顿珠出生于西藏东部的安多,被世人公认为十三世达赖喇嘛的转世。 1940 年 1 月 26 日,摄政熱振活佛请求中央政府免除拉姆顿珠使用金瓮抽签成为第十四世达赖喇嘛的程序。 [39] [40]该请求得到了中央政府的批准。 [41] 1939年,拉萨违背中国政府的意愿,向从西宁统治青海的回族军阀马步芳支付了40万龙洋赎金后,马步芳释放他前往拉萨。藏历新年之际,甘丹颇章政府在布达拉宫为他加冕。 [42] [43]

中华人民共和国声称国民党政府“批准”了现任十四世达赖喇嘛,由国民党代表吴忠信将军主持了仪式; 1940年2月的批准令和仪式的纪录片都完好无损。 [38]据茨仁夏加说,吴中信(连同其他外国代表)出席了仪式,但没有证据表明是他主持的。 [21]出席仪式的英国代表巴兹尔·古尔德爵士见证了中国声称主持仪式的虚假性。他对中国账户的批评如下:

The report was issued in the Chinese Press that Mr Wu had escorted the Dalai Lama to his throne and announced his installation, that the Dalai Lama had returned thanks, and prostrated himself in token of his gratitude. Every one of these Chinese claims was false. Mr Wu was merely a passive spectator. He did no more than present a ceremonial scarf, as was done by the others, including the British Representative. But the Chinese have the ear of the world, and can later refer to their press records and present an account of historical events that is wholly untrue. Tibet has no newspapers, either in English or Tibetan, and has therefore no means of exposing these falsehoods.[44]

藏族作家尼玛坚赞写道,根据藏族传统,没有主持活动这样的事情,并写道在通讯文件中很多地方都使用了“主持”这个词。这个词的意思与我们今天所理解的不同。他补充说,吴忠信在此次活动上花费了大量的时间和精力,他主持或组织活动的效果非常明显。 [45]

1942年,美国政府告诉蒋介石政府,它从未对中国对西藏的主张提出异议。 [46] 1944 年,美国战争部制作了一系列关于我们为什么而战的七部纪录片;在第六个系列“中国之战”中,西藏被错误地称为中国的一个省。 (正式名称是西藏地区,它不是一个省。 ) [47] 1944年,二战期间,两位奥地利登山者海因里希·哈勒和彼得·奥夫施奈特来到拉萨,在那里,哈勒成为年轻达赖喇嘛的导师和朋友,让他对西方文化和现代社会有了深入的了解,直到 1949 年哈勒选择离开。

西藏于1942年设立外交部,并于1946年分别向中国和印度(与二战结束有关)派出祝贺团。访华使团收到一封致中国国家主席蒋介石的信,信中说:“我们将继续维护西藏作为一个由历届达赖喇嘛通过真正的宗教政治统治统治的国家的独立性。”代表团同意以观察员身份出席在南京举行的中国制宪会议。 [48]

在蒋介石国民党政府的命令下,马步芳于 1942 年修复了玉树机场,以阻止西藏独立。 蒋还命令马步芳在 1942 年让他的穆斯林士兵对入侵西藏保持警惕。 [49] [50]马步芳应允,将数千名大军调往西藏边境。 [51]蒋还威胁西藏人,如果他们不遵守,就用轰炸。

1947年西藏派代表团参加在印度新德里召开的亚洲关系会议,在会上表示自己是一个独立国家,印度在1947年至1954年承认其为独立国家。 [52]这可能是西藏国旗首次出现在公共集会上。 [53]

1947年在西藏旅行数月的法国医生安德烈·米戈(André Migot) 描述了西藏和中国之间复杂的边界安排,以及它们是如何发展的: [54]

To offset the damage done to their interests by the [1906] treaty between England and Tibet, the Chinese set about extending westwards the sphere of their direct control and began to colonize the country round Batang. The Tibetans reacted vigorously. The Chinese governor was killed on his way to Chamdo and his army put to flight after an action near Batang; several missionaries were also murdered, and Chinese fortunes were at a low ebb when a special commissioner called Chao Yu-fong appeared on the scene.

Acting with a savagery which earned him the sobriquet of "The Butcher of Monks," he swept down on Batang, sacked the lamasery, pushed on to Chamdo, and in a series of victorious campaigns which brought his army to the gates of Lhasa, re-established order and reasserted Chinese domination over Tibet. In 1909 he recommended that Sikang should be constituted a separate province comprising thirty-six subprefectures with Batang as the capital. This project was not carried out until later, and then in modified form, for the Chinese Revolution of 1911 brought Chao's career to an end and he was shortly afterwards assassinated by his compatriots.

The troubled early years of the Chinese Republic saw the rebellion of most of the tributary chieftains, a number of pitched battles between Chinese and Tibetans, and many strange happenings in which tragedy, comedy, and (of course) religion all had a part to play. In 1914 Great Britain, China, and Tibet met at the conference table to try to restore peace, but this conclave broke up after failing to reach agreement on the fundamental question of the Sino-Tibetan frontier. This, since about 1918, has been recognized for practical purposes as following the course of the Upper Yangtze. In these years the Chinese had too many other preoccupations to bother about reconquering Tibet. However, things gradually quieted down, and in 1927 the province of Sikang was brought into being, but it consisted of only twenty-seven subprefectures instead of the thirty-six visualized by the man who conceived the idea. China had lost, in the course of a decade, all the territory which the Butcher had overrun.

Since then Sikang has been relatively peaceful, but this short synopsis of the province's history makes it easy to understand how precarious this state of affairs is bound to be. Chinese control was little more than nominal; I was often to have first-hand experience of its ineffectiveness. To govern a territory of this kind it is not enough to station, in isolated villages separated from each other by many days' journey, a few unimpressive officials and a handful of ragged soldiers. The Tibetans completely disregarded the Chinese administration and obeyed only their own chiefs. One very simple fact illustrates the true status of Sikang's Chinese rulers: nobody in the province would accept Chinese currency, and the officials, unable to buy anything with their money, were forced to subsist by a process of barter.

Once you are outside the North Gate [of Dardo or Kangting], you say good-by to Chinese civilization and its amenities and you begin to lead a different kind of life altogether. Although on paper the wide territories to the north of the city form part of the Chinese provinces of Sikang and Tsinghai, the real frontier between China and Tibet runs through Kangting, or perhaps just outside it. The empirical line which Chinese cartographers, more concerned with prestige than with accuracy, draw on their maps bears no relation to accuracy.

——安德烈·米戈(André Migot),Tibetan Marches[55]

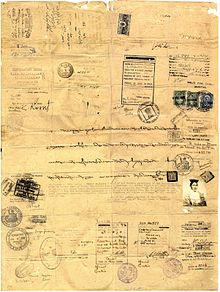

1947-49 年,拉萨派出了一个由财政部长夏格巴·旺秋德丹率领的贸易代表团前往印度、中国、香港、美国和英国。被访问的国家小心翼翼地不表达支持西藏独立于中国的说法,也没有与代表团讨论政治问题。 [10]这些贸易使团官员持新签发的西藏护照经香港进入中国,并在中国驻印度领事馆申请并在中国逗留了三个月。然而,其他国家确实允许代表团使用西藏政府签发的护照旅行。美国非正式地接待了贸易代表团。 1948 年,代表团在伦敦会见了英国首相克莱门特·艾德礼[56]

中华人民共和国吞并

[编辑]1949年,当时共产党控制中国,噶厦政府不顾中国国民党和中国共产党的抗议,将所有的中国官员驱逐出西藏。 [21] 1949年10月1日,十世班禅给北京写了一封电报,表达了对中国西北解放和中华人民共和国成立的祝贺,并对西藏不可避免的解放感到兴奋。 [57]由毛泽东领导的中国共产党政府于10月上台,很快就在西藏宣布新的中国存在。 1950年6月,英国政府在下议院表示,英国政府“一直准备承认中国对西藏的宗主权,但前提是西藏被视为自治的”。 [58] 1950年10月,中国人民解放军进入昌都藏区,击败了西藏军队的零星抵抗。 1951年,以阿沛·阿旺晋美为首的西藏当局代表在达赖喇嘛的授权下[59]在北京与中国政府进行谈判。它导致了十七点协议,确认了中国对西藏的主权。几个月后,该协议在拉萨获得批准。 [10]中国将整个过程描述为“西藏和平解放”。 [60]

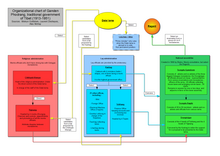

政治

[编辑]政府

[编辑]

军事

[编辑]

1910年代十三世达赖喇嘛完全控制西藏后,他开始在英国的支持下建立西藏军队,提供顾问和武器。这支军队应该足够庞大和现代化,不仅可以保卫西藏,而且还可以征服周边地区,如藏族人民居住的康区。西藏军队在十三世达赖喇嘛在位期间不断扩大, [61]到 1936 年约有 10,000 名士兵。在当时,这些是装备精良、训练有素的步兵,尽管军队几乎完全缺乏机枪、大炮、飞机和坦克。 [61]除了正规军外,西藏还动用了大量装备简陋的乡村民兵。 [61] 1920年代和1930年代,考虑到藏军的火力通常被对手击败,西藏军队在对抗中国各军阀方面表现相对较好。 [61]总体而言,藏军在军阀时代被证明是“无畏强悍的战士”。 [61]

尽管如此,在 1950 年中国入侵期间,西藏军队完全不足以抵抗中国人民解放军。它因此瓦解和在没有太多抵抗的情况下投降。 [62]

邮政服务

[编辑]

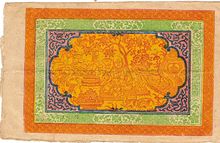

-

1912年发行的雪狮邮票

-

1912年发行的雪狮邮票

-

1912年发行的雪狮邮票

-

1912年发行的雪狮邮票

-

1912年发行的雪狮邮票

-

1912年发行的雪狮邮票

-

1920年发行的雪狮邮票

-

1933年发行的雪狮邮票

西藏于1912年设立了自己的邮政服务。西藏在拉萨印刷了第一张邮票,并于1912年发行。西藏于1950年发行了电报邮票。

外交关系

[编辑]民国军阀使中国分裂,十三世达赖喇嘛统治,但他的统治标志着与汉族和穆斯林军阀的边界冲突,西藏人失去了大部分时间。当时,西藏政府控制了所有的衛藏(Dbus-gtsang)和西部康区(Khams),大致与今天西藏自治区的边界重合。与长江相隔的东康区,在中国军阀刘文辉的控制之下。安多局势(青海)更复杂,与西宁经1928年后控制区回族军阀马步芳家族被称为穆斯林军阀的马家军,谁一直力图在安多休息施加控制(青海) . 1915年至1927年间,康南连同云南其他地区属于滇系軍閥,然后是总督兼军阀龙云,直到中国内战快结束时,杜玉明在蒋中正的命令下将他撤职。在中国控制的领土内,在国民党平定青海期间,正在对青海的西藏叛乱分子发动战争。

1918年,拉萨重新控制昌都和康区西部。停战协议将边界设在长江。此时的西藏政府控制了长江以西的所有乌藏和康区,与今日西藏自治区的边界大致相同。东康区由不同效忠的当地西藏王子统治。青海由回族和亲国民党军阀马步芳控制。 1932年西藏在青海玉树争夺一座寺院后,于1932年入侵青海,企图夺取青海省南部地区。马步芳率领青海军大败藏军。

在20世纪的20年代和30年代,中国被内战分裂,并陷入抗日战争,但从未放弃拥有西藏的主权,并偶尔尝试断言它。

1932年,十三世达赖喇嘛企图夺取青海和西康领土,在汉藏战争中,马步芳、刘文辉率领的国民革命军四川汉族联军和青海回族军大败藏军。他们警告藏人不要再过金沙江。 [63]双方签署了休战协议,结束了战斗。 [64] [65]达赖喇嘛在他的军队被击败后,曾向印度的英国人发出电报寻求帮助,并开始贬低他投降的将军们。 [66]

1936年,盛世才将3万名哈萨克人从新疆驱逐到青海后,马步芳将军率领的回族屠杀了他们的穆斯林哈萨克同胞,直到剩下135人。 [67] [68] [69] ]

7000多名哈萨克人从北疆经甘肃逃往藏青高原地区,大肆破坏,马步芳将哈萨克人归入青海指定牧场解决了问题,但该地区的回族、藏族和哈萨克族继续发生冲突互相反对。 [70]

哈萨克人经甘肃、青海进入西藏时,藏人与哈萨克人进行了进攻和战斗。

在西藏北部,哈萨克人与西藏士兵发生冲突,然后哈萨克人被送往拉达克。 [70]

当哈萨克人进入西藏时,西藏军队在拉萨以东400英里的昌都抢劫并杀害了哈萨克人。 [71] [72]

1934年、1935年、1936年至1938年从库米尔·埃利克桑率领克雷哈萨克人迁移到甘肃,估计有1.8万人,先后进入甘肃和青海。 [73]

1951年,维吾尔族Yulbars可汗在逃离新疆前往加尔各答时遭到西藏军队的袭击。

1950 年 4 月 29 日,反共产主义的美国中央情报局特工道格拉斯·麦基尔南 (Douglas Mackiernan)被西藏军队杀害。

经济

[编辑]货币

[编辑]

西藏政府发行纸币和硬币。

社会与文化

[编辑]佛教和西藏研究教授唐纳德·S·洛佩兹(Donald S. Lopez) 当时表示:

这些机构团体一直保持着强大的权力直到 1959 年。 [74]

十三世达赖喇嘛在 20 世纪的第一个十年改革了原有的农奴制度,到 1950 年,奴隶制本身在西藏中部可能已经不复存在,尽管可能在某些边境地区仍然存在。 [75]例如,奴隶制确实存在于像春比谷这样的地方,尽管像查尔斯·贝尔这样的英国观察家称其为“温和的”, [76]和乞丐 ( ragyabas ) 是地方性的。然而,前中国的社会制度相当复杂。

庄园( shiga ),与英国的庄园制度大致相似,由国家授予,是世袭的,但可以撤销。作为农业财产,它们由两种类型组成:贵族或修道院机构拥有的土地(直辖土地)和中央政府拥有的村庄土地(土地或村地),尽管由地区行政人员管理。直辖领土地平均占庄园的二分之一到四分之三。 Villein 土地属于庄园,但租户通常行使世袭用益权以换取履行他们的徭役义务。贵族和寺院系统以外的藏人被归类为农奴,但存在两种类型,功能上可与佃农相媲美。农奴,或“小烟”( düchung ),必须在庄园工作,作为一种徭役义务( ula ),但他们拥有自己的土地所有权,拥有私人物品,可以在他们进贡所需的时间之外自由行动。劳动,并且免于纳税义务。他们可以积累财富,有时自己也成为庄园的贷方,并可以起诉庄园主:乡村农奴 ( tralpa ) 受约束于他们的村庄,但仅用于税收和徭役目的,例如公路运输税 ( ula ),并且只需要缴税。一半的村农奴是租借农奴( mi-bog ),意味着他们已经购买了自由。庄园主对附属农奴行使广泛的权利,逃亡或修道生活是唯一的救济场所。然而,不存在将逃跑的农奴恢复到他们的庄园的机制,也不存在强制执行奴役的手段,尽管庄园主有权追捕并强行将他们送回土地。

农奴若连续三年不在自己的庄园内,将自动获得平民( chimi )身份或重新归类为中央政府的农奴。地主可以将他们的臣民交给其他地主或富农劳动,尽管这种做法在西藏并不常见。尽管结构上很僵硬,但该制度在基层表现出相当大的灵活性,农民一旦履行了他们的徭役义务,就不受庄园主的约束。根据沃伦·W·史密斯的说法,从历史上看,对该系统的不满或滥用似乎很少见。 [77] [59]西藏远非贤能,但达赖喇嘛是从农民家庭的儿子中招募的,游牧民族的儿子可以崛起,掌握寺院制度,成为学者和方丈。 [78]

参见

[编辑]笔记

[编辑]

参考

[编辑]引文

[编辑]- ^ 1.0 1.1 Lin (2011); Anand (2013)

- ^ Perkins, Dorothy. Encyclopedia of China: History and Culture. Routledge. 2013 [5 December 2020]. ISBN 978-1-135-93562-7. (原始内容存档于15 July 2021) (英语).

- ^ Fravel, M. Taylor. Strong Borders, Secure Nation: Cooperation and Conflict in China's Territorial Disputes. Princeton University Press. 2008 [5 December 2020]. ISBN 978-1-4008-2887-6. (原始内容存档于15 July 2021) (英语).

- ^ 今日郵政. 今日郵政月刊社. 1997 [8 September 2020]. (原始内容存档于15 July 2021) (中文).

- ^ Ling, Chunsheng. Bian jiang wen hua lun ji. Zhonghua wen hua chu ban shi ye wei yuan hui, Min guo 42. 1953 [8 September 2020]. (原始内容存档于15 July 2021) (中文).

- ^ Ram Rahul, Central Asia: an outline history 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期13 October 2017., New Delhi, Concept Publishing Company, 1997, p. 42 : "From then [1720] until the fall of the Manchu dynasty in 1912, the Manchu Ch'ing government stationed an Amban, a Manchu mandarin, and a military escort in Tibet."

- ^ Barry Sautman, Tibet's Putative Statehood and International Law, in Chinese Journal of International Law, Vol. 9, Issue 1, 2010, p. 127-142: "Through its Lifan Yuan (Office of Border Affairs ...), the Chinese government handled Tibet's foreign and many of its domestic affairs.

- ^ Zhu (2020): "Taking advantage of the chaos in China, Mongolia and Tibet both declared their independence towards the end of 1911, expelled the Chinese ambans (residents) and garrisons, and established independent governments.

- ^ Melvyn C. Goldstein (with Cynthia M. Beall), Nomads of Western Tibet — The Survival of a Way of Life 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期7 November 2017., University of California Press, 1990, 191 p., p. 50 (Historical background).

- ^ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 10.5 Goldstein (1989).

- ^ Goldstein (1997),"Tibetan Attempts to Modernize", p. 37: "Chinese fortunes in Tibet improved slightly after the death of the thirteenth Dalai Lama when Tibet allowed a "condolence mission" sent by Guomindang government of Chiang Kaishek to visit Lhasa, and then permitted it to open an office to facilitate negotiations aimed at resolving the Tibet Question.

- ^ Lin (2011): "From [1792] on, the Qing dynasty became increasingly preoccupied with problems in the interior, and court officials in Peking found it less and less easy to intervene in Tibetan affairs.... by the second half of the nineteenth century, the Qing ambans, who represented the Qing emperor and Qing authority, could do little more than exercise ritualistic and symbolic influence."

- ^ Tanner, Harold. China: A History. 2009: 419 [5 December 2020]. ISBN 978-0872209152. (原始内容存档于11 June 2021).

- ^ Esherick, Joseph; Kayali, Hasan; Van Young, Eric. Empire to Nation: Historical Perspectives on the Making of the Modern World. 2006: 245 [5 December 2020]. ISBN 9780742578159. (原始内容存档于23 June 2021).

- ^ Zhai, Zhiyong. 憲法何以中國. 2017: 190 [21 July 2021]. ISBN 9789629373214. (原始内容存档于23 June 2021).

- ^ Gao, Quanxi. 政治憲法與未來憲制. 2016: 273 [21 July 2021]. ISBN 9789629372910. (原始内容存档于23 June 2021).

- ^ Zhao, Suisheng. A Nation-state by Construction: Dynamics of Modern Chinese Nationalism. 2004: 68 [5 December 2020]. ISBN 9780804750011. (原始内容存档于11 June 2021).

- ^ Goldstein (1997).

- ^ Goldstein (1997)

- ^ Tibet Justice Center – Legal Materials on Tibet – Tibet – Proclamation Issued by His Holiness the Dalai Lama XIII (1913) [106]. [16 March 2009]. (原始内容存档于4 February 2019).

- ^ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 21.4 21.5 21.6 21.7 Shakya (1999).

- ^ 22.0 22.1 Udo B. Barkmann, Geschichte der Mongolei, Bonn 1999, p380ff

- ^ Grunfeld 1996,第65頁.

- ^ Bell (1924)

- ^ Quoted by Sir Charles Bell, "Tibet and Her Neighbours", Pacific Affairs(Dec 1937), pp. 435–6, a high Tibetan official pointed our years later that there was "no need for a treaty; we would always help each other if we could."

- ^ Dogovor 1913 g. mezhdu Mongoliyey i Tibetom: novyye dannyye Договор 1913 г. между Монголией и Тибетом: новые данные [1913 Treaty between Mongolia and Tibet: New Data]. [13 January 2013]. (原始内容存档于11 September 2020).

- ^ Tibet Justice Center – Legal Materials on Tibet – Treaties and Conventions Relating to Tibet – Convention Between Great Britain, China, and Tibet, Simla (1914) [400]. [16 March 2009]. (原始内容存档于9 September 2020).

- ^ Article 2 of the Simla Convention 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期15 February 2011.

- ^ Appendix of the Simla Convention 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期15 February 2011.

- ^ Tibet Justice Center – Legal Materials on Tibet – Treaties and Conventions Relating to Tibet – Convention Between Great Britain and Russia (1907)[391]. [16 March 2009]. (原始内容存档于5 February 2019).

- ^ Lin (2004).

- ^ Free Tibet Campaign, "Tibet Facts No.17: British Relations with Tibet" 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期11 April 2008..

- ^ 33.0 33.1 Lamb (1966b).

- ^ Republic of China (1912–1949). China's Tibet: Facts & Figures 2002. [17 April 2006]. (原始内容存档于3 March 2016).

- ^ Chambers's Encyclopaedia, Volume XIII, Pergamaon Press, 1967, p. 638

- ^ Reports by F.W. Williamson, British political officer in Sikkim, India Office Record, L/PS/12/4175, dated 20 January 1935

- ^ Kuzmin, S.L. Hidden Tibet: History of Independence and Occupation.

- ^ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Tibet during the Republic of China (1912–1949) 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期22 November 2009.

- ^ Goldstein 1991,第328–頁.

- ^ Report to Wu Zhongxin from the Regent Reting Rinpoche Regarding the Process of Searching and Recognizing the Thirteenth Dalai lama's Reincarnated Soul Boy as well as the Request for an Exemption to Drawing Lots. The Reincarnation of Living Buddhas. Museum of Tibetan Culture of China Tibetology Research Center. 1940.

- ^ Executive Yuan's Report to the National Government Regarding the Request to Approve Lhamo Thondup to Succeed the Fourteenth Dalai lama and to Appropriate Expenditure for His Enthronement. The Reincarnation of Living Buddhas. Museum of Tibetan Culture of China Tibetology Research Center. 1940.

- ^ Bell (1946).

- ^ Richardson (1984).

- ^ Bell (1946),第400頁.

- ^ 王家伟; 尼玛坚赞. 中国西藏的历史地位 [Wang Jiawei; Nima Gyaltsen (1997). The historical position of Tibet in China. China Communication Publishing House]. 五洲传播出版社. 1997: 133–. ISBN 978-7-80113-303-8.

- ^ Testimony by Kent M. Wiedemann, Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs before Subcommittee on East Asian and Pacific Affairs, Senate Foreign Relations Committee (online version 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期13 January 2012.), 1995

- ^ Frank Capra, Why We Fight: The Battle of China, Eric Spiegelman, [7 July 2020]

- ^ Smith, Daniel, "Self-Determination in Tibet: The Politics of Remedies" 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期28 May 2011..

- ^ Lin, Hsiao-ting. War or Stratagem? Reassessing China's Military Advance towards Tibet, 1942–1943. [28 June 2010]. (原始内容存档于3 March 2016).

- ^ chiang ma bufang qinghai troops sino tibetan border site:journals.cambridge.org – Google Search. [18 March 2020]. (原始内容存档于13 March 2021). 外部链接存在于

|title=(帮助) - ^ Barrett, David P.; Shyu, Lawrence N. China in the anti-Japanese War, 1937–1945: politics, culture and society. Peter Lang. 2001: 98 [28 June 2010]. ISBN 0-8204-4556-8. (原始内容存档于24 June 2021).

- ^ India Should Revisit its Tibet Policy. Institute for Defense Studies and Analysis. [5 January 2009]. (原始内容存档于21 April 2008).

- ^ CTA's Response to Chinese Government Allegations: Part Four. Website of Central Tibetan Administration. [5 January 2009]. (原始内容存档于16 November 2008).

- ^ Migot, André (1955).

- ^ Tibetan Marches 互联网档案馆的存檔,存档日期16 May 2021.. André Migot. Translated from the French by Peter Fleming, p. 101. (1955). E. P. Dutton & Co. Inc. New York.

- ^ Farrington, Anthony. Britain, China, and Tibet, 1904–1950. International Institute for Asian Studies. (原始内容存档于29 November 2018).

- ^ 西藏现代史 [History of Tibet]. 香港大學出版社 [Hong Kong University Publisher]. July 2014. ISBN 9789888139699.

"北京中央人民政府毛主席、中国人民解放军朱德司令钧鉴:钧座以大智大勇之略,成救国救民之业,义师所至,全国欢腾,班禅世受国恩,备荷优崇。二十余年来,为了西藏领土主权之完整,呼吁奔走,未尝稍懈。第以未获结果,良用疚心。刻下羁留青海,待命返藏。兹幸在钧座领导之下,西北已获解放,中央人民政府成立,凡有血气,同声鼓舞。今后人民之康乐可期,国家之复兴有望。西藏解放,指日可待。班禅谨代表全藏人民,向钧座致崇高无上之敬意,并矢拥护爱戴之忱。”—十世班禅致中华人民共和国中央人民政府电报 [To President Mao of the Central People's Government of Beijing and Commander Zhu De of the Chinese People's Liberation Army: The scorpion is based on the wisdom of the great wisdom and the courage to save the country and the people. The whole country is full of joy, and the Panchen Lama is blessed by the country. For more than 20 years, I have been dealing with integrity of Tibet territorial sovereignty, without rest. Since result has not been obtained, I felt guilty. I will stay in Qinghai and wait for possible return. Fortunately, under your leadership, the northwest has been liberated, and the Central People’s Government has been established, we're all excited. In the future, the people’s well-being can be expected, and the country’s revival is expected. The liberation of Tibet is just around the corner. On behalf of the entire Tibetan people, please accept my supreme respect and support. " ---- The 10th Panchen Lama to the Central People's Government of the People's Republic of China]

- ^ TIBET (AUTONOMY) (Hansard, 21 June 1950). [21 April 2009]. (原始内容存档于27 October 2020).

- ^ 59.0 59.1 Goldstein (2007).

- ^ Peaceful Liberation of Tibet. china.org.cn. [12 April 2015]. (原始内容存档于16 June 2017).

- ^ 61.0 61.1 61.2 61.3 61.4 Jowett (2017).

- ^ van Schaik (2013).

- ^ Liu, Xiaoyuan. Frontier passages: ethnopolitics and the rise of Chinese communism, 1921–1945. Stanford University Press. 2004: 89 [28 June 2010]. ISBN 0-8047-4960-4. (原始内容存档于15 July 2021).

- ^ Oriental Society of Australia. The Journal of the Oriental Society of Australia, Volumes 31–34. Oriental Society of Australia. 2000: 35, 37 [28 June 2010]. (原始内容存档于15 July 2021).

- ^ Michael Gervers, Wayne Schlepp, Joint Centre for Asia Pacific Studies. Historical themes and current change in Central and Inner Asia: papers presented at the Central and Inner Asian Seminar, University of Toronto, April 25–26, 1997, Volume 1997. Joint Centre for Asia Pacific Studies. 1998: 73, 74, 76 [5 December 2020]. ISBN 1-895296-34-X. (原始内容存档于15 July 2021).

- ^ K. Dhondup. The water-bird and other years: a history of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama and after. Rangwang Publishers. 1986: 60 [5 December 2020]. (原始内容存档于15 July 2021).

- ^ American Academy of Political and Social Science. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Volume 277. American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1951: 152 [28 June 2010]. (原始内容存档于15 July 2021).

- ^ American Academy of Political and Social Science. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Volumes 276–278. American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1951: 152 [28 June 2010]. (原始内容存档于15 July 2021).

- ^ American Academy of Political and Social Science. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, Volume 277. American Academy of Political and Social Science. 1951: 152 [29 September 2012]. (原始内容存档于8 May 2021).

A group of Kazakhs, originally numbering over 20000 people when expelled from Sinkiang by Sheng Shih-ts'ai in 1936, was reduced, after repeated massacres by their Chinese coreligionists under Ma Pu-fang, to a scattered 135 people.

- ^ 70.0 70.1 Lin (2011).

- ^ Blackwood's Magazine. William Blackwood. 1948: 407 [6 October 2015]. (原始内容存档于15 July 2021).

- ^ Devlet, Nadir. STUDIES IN THE POLITICS, HISTORY AND CULTURE OF TURKIC PEOPLES. [3 December 2017]. (原始内容存档于21 July 2021) (英语).

- ^ Benson, Linda. The Kazaks of China: Essays on an Ethnic Minority. Ubsaliensis S. Academiae. 1988: 195 [6 October 2015]. ISBN 978-91-554-2255-4. (原始内容存档于15 July 2021).

- ^ Pradyumna P. Karan, The Changing Face of Tibet: The Impact of Chinese Communist Ideology on the Landscape, University Press of Kentucky, 1976, p.64.

- ^ Warren W. Smith, Jr.China's Tibet?: Autonomy Or Assimilation, Rowman & Littlefield, 2009 p.14

- ^ Alex McKay, (ed.

- ^ Warren W. Smith, Jr. China's Tibet?: Autonomy Or Assimilation, pp.14–15.

- ^ Donald S Lopez Jr., Prisoners of Shangri-La, p. 9.

[[Category:1951年中國廢除]] [[Category:1912年亞洲建立]] [[Category:已不存在的亞洲君主國]] [[Category:已不存在的君主國]] [[Category:未被普遍承认的历史国家]] [[Category:冷战时期的历史政权]] [[Category:中國古代民族與國家]] [[Category:亞洲爭議地區]] [[Category:前神权政体]] [[Category:已不存在的亞洲國家]] [[Category:西藏歷史]] [[Category:含有哈佛参考文献格式系列模板链接指向错误的页面]] [[Category:Webarchive模板wayback链接]]