用户:Allthingsgo/List of Christians in science and technology

外观

这是一份基督徒在科学和技术方面的清单。 名单上的人应该具有与其著名活动或公共生活相关的基督教信仰,并公开自称为基督徒或基督教派系。

在18世纪之前

[编辑]

- 宾根的希尔德加德(1098-1179) : 也被称为圣希尔德加德和莱茵河的西比尔,是德国的本笃会修女。 她被认为是德国科学自然史的奠基人[2]

- 罗伯特·格罗斯泰斯特: 林肯主教,他是13世纪上半叶英国知识分子运动的中心人物,并被认为是牛津大学科学思想的奠基人。 他对自然界非常感兴趣,并撰写了关于光学、天文学和几何学的数学科学的文章。 他重申,应当利用实验来验证一个理论,检验其后果,并大大增加科学方法的发展。[3]

- Albertus Magnus (c. 1193-1280) : 天主教科学家的守护神,他可能是第一个将砷分离出来的人。 他写道:"自然科学不在于批准别人的言论,而在于寻找现象的原因。" 然而,他拒绝了与天主教相冲突的亚里士多德主义元素,并利用他的信仰以及新柏拉图理念来"平衡""麻烦的"亚里士多德主义元素。[note 1][4]

- Jean Buridan (1300-58) : 法国哲学家和牧师。 他对科学最重要的贡献之一是冲力说的发展,解释了射弹和物体自由落体的运动。 这一理论让位于伽利略的动力学和艾萨克 · 牛顿著名的惯性原理。

- Nicole Oresme (c.1323-1382) : 神学家和利雪的主教,他是现代科学的早期创始人和普及者之一。 他的许多科学贡献之一就是发现了光线穿过大气折射的曲率。[5]

- 尼古拉(1401-1464) : 天主教红衣主教和神学家,通过发展无穷小和相对运动的概念,为数学领域做出了贡献。 他的哲学思考也预测了哥白尼的地狱世界观。[6]

- 奥托 · 布伦芬尔斯(1488-1534) : 来自美因茨的神学家和植物学家。 他的《 virorum 》被认为是第一本关于从天主教会分离出来的福音派教派历史的第一本书。 在植物学领域,他的赫巴拉姆(Herbarum vivae icones)作为"植物学之父"而赢得了赞誉。[7]

- 威廉 · 特纳(c. 1508-1568) : 有时被称为"英国植物学之父",也是一位鸟类学家。 他因宣扬支持宗教改革而被捕。 后来他成为了威尔斯大教堂的院长,但因不符合规定而被开除。[8]

- Ignazio Danti (1536-1586) : 作为阿拉特里的主教,他召集了一个主教教区来处理虐待事件。 他还是一位数学家,他写过关于欧几里得的文章,他是一位天文学家,也是一位机械设备设计师。[9]

- 弗朗西斯 · 培根(1561-1626) : 在经验主义之父中被认为建立了实验科学的归纳方法,今天被称为科学方法。[10][11]

- 伽利略(1564-1642) : 意大利天文学家、物理学家、工程师、哲学家和数学家,他在文艺复兴时期在科学革命中扮演了重要角色。[12][13]

- Laurentius Gothus (1565-1646) : 天文学和乌普萨拉大主教学教授。 他写的是关于天文学和神学的。[14]

- 皮埃尔 · 加森迪(Pierre Gassendi)(1592-1655) : 试图调和原子论与基督教的天主教牧师。 他还出版了第一本关于水星凌日的著作,并修正了地中海的经纬度。[15]

- 莱塔的安东 · 玛利亚(1597-1660) : 卡普钦天文学家。 他把他的一本天文学书献给了耶稣基督,一个"theo-astronomy"的作品是献给马利亚的,他想知道其他星球上的生命是否像人类一样被原罪所诅咒[16]

- 布莱斯 · 帕斯卡(1623-1662) : 詹森主义思想家; 以帕斯卡定律(物理学)、帕斯卡定理(数学)和帕斯卡的赌注(神学)而闻名。[note 2][17]

- 尼古拉斯 · 斯坦诺(1638-1686) : 路德教徒皈依天主教,他在这一信仰中的美化发生在1987年。 作为一名科学家,他被认为是解剖学和地质学的先驱,但在他的改宗者之后,他在很大程度上放弃了科学。[18][19]

- 艾萨克 · 巴罗(1630-1677) : 英国神学家、科学家和数学家。 他写了《信条》、《主祷文》、《十诫》、《圣礼》和《几何主义论》。[20]

- 胡安 · 洛布科维茨(1606-1682) : Cistercian 和尚,10岁时曾研究过 Combinatorics 和发表的天文学图表。 他也做神学和布道的工作。[21]

- 赛斯 · 沃德(1617-1689) : 1649-1661年英国圣公会索尔兹伯里主教和萨维利安天文学教授。 他写了 Ismaelis Bullialdi astro-nomiae philolaicae fundamenta inquisitio brevis 和 Astronomia geometryica。 他还与托马斯 · 霍布斯有过神学 / 哲学上的争论,作为一个主教,他对非循规蹈矩者非常严厉。[22]

- 罗伯特 · 博伊尔(1627-1691) : 杰出的科学家和神学家,他认为科学研究可以改善对上帝的赞颂。[23][24] 作为一个坚强的基督教的辩护者,他被认为是化学史上最重要的人物之一。

- 牛顿(1643-1727) : 科学革命时期的杰出科学家。 物理学家,地心引力的发现者,一位炼金术士和一位痴迷于基督教的辩护者,痴迷于试图从《圣经》中分辨出被提升的日期。

- 约翰内斯 · 开普勒(1571-1630) : 科学革命的杰出天文学家发现了开普勒的行星运动定律。

公元1701-1800年(18世纪)

[编辑]- 约翰 · 雷(1627-1705) : 英国植物学家,他在《造物的作品》中写下了上帝的智慧。 (1691)约翰雷环境与基督教倡议也是以他命名的。[25][26]

- 戈特弗里德 · 莱布尼茨(1646-1716) : 他是一位哲学家,他发展了预先确立的和谐的哲学理论; 他也以乐观而著称,例如,他得出结论,认为我们的宇宙在某种程度上是上帝可能创造的最好的宇宙。 他还对数学、物理和技术做出了重大贡献。 他创造了步进计算器,他的《原形》涉及地质学和自然历史。 他是一位路德教徒,曾与天主教徒约翰 · 弗雷德里克(约翰 · 弗雷德里克)合作,希望天主教与路德教统一。[27]

- 斯蒂芬 · 哈雷斯(1677-1761) : 科普利奖章获得者对植物生理学研究具有重要意义。 作为一个发明者设计了一种通风系统,一种提取海水的方法,保存肉类的方法等等。 在宗教方面,他是英国圣公会的牧师,曾与基督教知识促进协会合作,并且是一个致力于在西印度群岛改造黑人奴隶的团体。[28]

- 弗明 · 阿鲍兹特(1679-1767) : 物理学家和神学家。 他将《新约》翻译成法文,并纠正了牛顿《原理》中的一个错误。[29]

- 伊曼纽·斯威登堡(1688-1772) : 他与瑞典皇家科学院进行了大量的科学研究,并委托他进行研究。[30] 他的宗教作品是斯威登伯格主义的基础,他的一些神学著作包含了一些科学假设,最引人注目的是太阳系起源的星云假说。[31]

- 阿尔布雷希特 · 冯 · 哈勒(1708-1777) : 瑞士解剖学家,被称为"现代生理学之父"的生理学家 作为一名新教徒,他参与了在格丁根建立改革宗教会的工作,作为一个对宗教问题感兴趣的人,他写了一封道歉信,这些信是他女儿用这个名字编写的。[32]

- Leonhard Euler (1707-1783) : 重要的数学家和物理学家,参见列昂哈德 · 尤勒名下的主题列表。 作为牧师的儿子,他在5月24日路德教会的圣人历上写了《抵抗神圣启示录》 ,反对自由思想家的反对意见,并在5月24日路德教会的圣人历上举行了纪念活动。[33]

- 米哈伊尔·瓦西里耶维奇·罗蒙诺索夫(1711-1765)俄罗斯东正教基督徒发现了金星的大气层,并制定了化学反应中的质量守恒定律。

- 安托万-洛朗·德·拉瓦锡(1743-1794) : 被认为是现代化学之父。 他以发现氧气在燃烧中的作用而闻名,发展化学命名,开发元素的初步周期表,以及质量守恒定律。 他是天主教徒,是圣经的守护者。[34]

- 赫尔曼·布尔哈夫(1668-1789) : 卓越的荷兰医生和植物学家,被称为临床教学的奠基人。 他对医学的宗教思想的集合,从拉丁语翻译成英语,被编译成 boerhaave s Orations。[35]

- 约翰 · 米歇尔(1724-1793) : 英国牧师,他在天文学、地质学、光学和万有引力等广泛的科学领域提供了开拓性的见解。[36][37]

- 玛利亚·阿涅西(1718-1799) : 数学家被任命为一个职位的本笃十四世。 她父亲去世后,她把一生都献给了宗教研究、慈善事业,最终成为了一名修女。[38]

- 卡尔 · 林奈(1707-1778) : 瑞典植物学家、医生和动物学家,"现代分类学之父"。

公元1801-1900年(19世纪)

[编辑]- 约瑟夫·普利斯特里(1733-1804) : 非 trinitarian clergyman,他创作了有争议的《基督教腐败史》。 他因发现氧气而受到赞誉。[note 3]

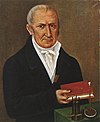

- 亚历山德罗·伏特(1745-1827) : 意大利物理学家发明了第一个电池。 伏特是以他的名字命名的。[39]

- 塞缪尔 · 文斯(1749-1821) : 剑桥天文学家和牧师。 为了回应休谟先生的反对意见,他写了关于流体运动和阻力理论以及基督教信誉的观察。 他在1780年获得了科普利奖章,那时这个时期还没有结束。[40]

- 艾萨克•米尔纳(Isaac Milner)(1750-1820) : 以制造亚硝酸的重要工序而闻名。 他同时也是一位福音派圣公会教徒,与他的兄弟共同撰写了基督教会的教会历史,并在威廉·威尔伯福斯的宗教觉醒中发挥了作用。 他还导致威廉 · 弗兰德被剑桥大学开除,原因是他声称是法国人对宗教的攻击。[41]

- 威廉 · 柯比(1759-1850) : 帕森自然主义者,他写了《论权力的智慧和上帝的善良》。 正如《创造动物》和《他们的历史、习惯和本能》中所体现的那样,是英国昆虫学的奠基人物。 是英国化学家、物理学家和气象学家。[42][43] 他以将原子理论引入化学而闻名。 他是奎克基督教徒。[44]

- 约翰 · 道尔顿(1766-1844) :

- 乔治 · 居维尔(1769-1832) : 法国自然学家和动物学家,有时被称为"古生物学之父"。

- 安德烈•玛丽•安培(Andre Marie Ampere)(1775-1836) : 经典电磁学的创始人之一。 电流单位,安培,是以他的名字命名的。[45]

- 奥林斯 · 格雷戈里(1774-1841) : 他在1793年写了《天文学和哲学课》 ,并于1802年成为皇家军事学院的数学硕士。 他1815年写的《基督教证据书》是由宗教道学会完成的。[46]

- 约翰·阿伯克龙比(众议员)(1780-1844) : 苏格兰医生和基督教哲学家创建了一本关于神经病理学的教科书。[47]

- 威廉·巴克兰(1784-1856) : 写《 Vindiciae Geologiae 》的英国圣公会牧师 / 地质学家; 或者地质学与宗教的联系解释。 他出生于1784年,但他的科学生活并没有在这里讨论的时期之前开始。[48]

- 玛丽安宁(1799-1847) : 古生物学家因在多塞特莱姆里吉斯发现某些化石而闻名。 安宁是虔诚的宗教信徒,参加了一个教会,然后是英国圣公会教堂。[49]

- 马歇尔大厅(1790-1857) : 著名的英国生理学家,他对解剖学的理解作出了贡献,并提出了医学科学中的一些技术。 作为一名虔诚的基督徒,他的宗教思想被他的遗孀(1861年)收录在传记《马歇尔庄园回忆录》中。[50] 他也是一个反对基于宗教理由的奴隶制的废奴主义者。 他认为奴隶制是对上帝的罪恶,是对基督教信仰的否定。[51]

- 拉斯 · 莱维 · l · 斯塔迪乌斯(1800-1861) : 植物学家在路德教中开始了一场名为 Laestadianism 的复兴运动。 这个运动是路德教最严格的形式之一。 作为一个植物学家,他引用了作者拉斯特,发现了四个物种。[52]

- 爱德华·希区柯克(1793-1864) : 地质学家、古生物学家和公理会牧师。 他在自然神学上工作,并在石化的轨道上写字。[53]

- 本杰明·西利曼(1779-1864) : 耶鲁大学的化学家和科学教育家; 第一个提炼石油的人,是美国最古老的科学杂志《美国科学杂志》的创始人。 作为一个直言不讳的基督徒,他是一个古老的创世主义者,公开反对物质主义。[54]

- 波恩哈德·黎曼: 牧师的儿子,他在19岁时进入哥廷根大学,最初是为了学习语言学和神学,以便成为一名牧师,帮助他的家庭理财。[note 4] 根据高斯的建议改成了数学。[55] 他对数学分析、数论和微分几何做出了持久的贡献,其中一些为后来的广义相对论发展提供了条件。

- 威廉 · 惠威尔(1794-1866) : 矿物学和道德哲学教授。 他在1819年写了一篇关于力学的基础论文,1833年,天文学和普通物理学考虑了自然神学。[56][57] 他创造了"科学家"、"物理学家"、"阳极"、"阴极"和许多其他常用科学词汇的词汇创造者。

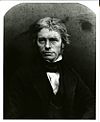

- 迈克尔 · 法拉第(1791-1867) : 格拉斯哥教会的长者,他在一次反对唯心论的演讲中讨论了科学与宗教的关系。[58][59] 他以在建立电磁理论方面的贡献而闻名,他在化学方面的工作,例如建立电解。

- 詹姆斯·大卫·福布斯(1809-1868) : 在热传导和地震学方面广泛工作的物理学家和冰川学家。 他是一位虔诚的基督徒,在《詹姆斯·大卫·福布斯》(1873)的作品中可见一斑。

- 查尔斯 · 巴贝奇(1791-1871) : 数学家和分析哲学家,被称为第一个计算机科学家谁起源了一个可编程计算机的想法。 他写了《第九部布里奇沃特论》 ,以及《哲学家生平》(1864)中的段落,在那里他提出了理性地捍卫对奇迹的信仰的论点。[60][61][62]

- 亚当 · 塞奇威克(1785-1873) : 英国圣公会的牧师和地质学家,他的《关于大学研究的论述》讨论了上帝与人的关系。 在科学领域,他赢得了科普利奖章和沃拉斯顿奖章。[63]

- 约翰 · 巴赫曼(1790-1874) : 写了许多科学文章,并命名了几种动物。 他还是路德教南方神学院的创始人,并写了关于路德教的著作。[64]

- 天坛(1794-1873) : 神父和天文学家在天文学研究中证明了神的力量和智慧。 他还成立了杜伦大学天文台,因此达勒姆盾牌被拍摄下来。[65]

- 罗伯特 · 梅因(1808-1878) : 1858年赢得英国皇家天文学会金质奖章的英国圣公会牧师。 罗伯特 · 梅因也在英国布里斯托尔协会布道。[66]

- 詹姆斯·克拉克·麦克斯韦(1831-1879) : 虽然小时候的 Clerk 被他的父亲带到了长老会医院,他的姑妈也把他送到了圣公会医院,而剑桥大学的一个年轻学生,他接受了福音教派的皈依,他形容这种转变使他对上帝之爱有了新的认识。[note 5] 麦克斯韦的福音主义"使他致力于反实证主义的立场。"[67][68] 他以在建立电磁理论(麦克斯韦方程式)和研究化学分子运动论方面的贡献而闻名。

- 詹姆斯 · 博维尔(1817-1880) : 加拿大内科医生和显微镜工作者,他是皇家医师学院的成员。 他是威廉•奥斯勒(William Osler)的导师,也是英国圣公会大臣和宗教作家的导师。[69]

- 安德鲁 · 普利查德(1804-1882) : 英国博物学家和自然历史交易者对显微镜作了重大改进,并撰写了关于水生微生物的标准工作。 他把大量精力投入到他所参加的教堂 Newington Green Unitarian 教堂。

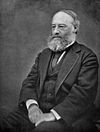

- 孟德尔(1822-1884) : 奥古斯丁 · 阿博是"现代遗传学之父",因为他对豌豆植物性状遗传的研究。[70] 他在教堂布道,其中一篇讲述复活节如何代表基督对死亡的胜利。[71]

- 刘易斯 · 卡罗尔(1832-1898) : 英国作家、数学家和英国圣公会执事。 罗宾斯和拉姆西对道奇森方法的研究,一种评估决定因素的方法,引导他们进入交替符号矩阵猜想,现在是一个定理。

- 海因里希 · 赫兹(1857-1894) : 德国物理学家第一次确凿地证明了电磁波的存在。

- 菲利普 · 亨利 · 戈斯(1810-1888) : 1854年写《水族馆》的海洋生物学家,和海洋动物学手册(1855-56)。 作为一个基督教原教旨主义者,他创造了 Omphalos (神学)的概念,因此他更加出名,或者声名狼藉。[72]

- 格雷(1810-1888) : 他的《灰色手册》仍然是植物学中的一项重要工作。 他的达尔文纳纳书中有题为"自然选择与自然神学不矛盾"、"进化论与神学"和"进化心灵学" 序言表明他在这些宗教问题上遵守了尼西亚信条。[73]

- 朱利安 · 特尼森 · 伍兹(1832-1889) : 圣心圣约瑟姐妹会的共同创始人,在死前不久获得了克拉克奖章。 一张他被埋葬的 Waverley Cemetery 的照片。[74]

- 路易斯 · 巴斯德(1822-1895) : 法国生物学家、微生物学家和化学家,他发现了疫苗接种、微生物发酵和巴氏灭菌的原理。

- 詹姆斯·德怀特·丹纳(1813-1895) : 地质学家、矿物学家和动物学家。 他获得了科普利奖章,沃拉斯顿奖章和克拉克奖章。 他还写了一本名为《科学与圣经》的书,他的信仰被描述为"既正统又强烈"[75]

- 詹姆斯·普雷斯科特·焦耳(1818-1889) : Joule 研究了热的性质,发现了它与机械工作的关系。 这导致了能量守恒定律的产生,从而导致了能量守恒定律的发展。 来自 SI 的能量单位 Joule,是以 James Joule 命名的。[76]

- 约翰·威廉·道森(1820-1899) : 加拿大地质学家,加拿大皇家学会第一任主席,同时担任英国和美国科学进步协会的总统。 一个长老会教徒,他反对达尔文的理论,来写《世界的起源》 ,根据《启示录》和《科学》(1877) ,他把他的神学和科学观点放在一起。[77]

- 阿曼德 · 大卫(1826-1900) : 中国天主教传教士和拉扎尔主义者的成员,他认为他的宗教义务是他的主要关切。 他还是一位植物学家,他的缩写是大卫,作为一个动物学家,他描述了几个新西方物种。[78]

- 约瑟夫 · 利斯特(1827-1912)是英国外科医生,也是消毒手术的先驱。 后来,他离开了贵格会,加入了苏格兰圣公会。[79]

- Mdmitri Mendeleev (1834-1907)是一位俄罗斯化学家和东正教基督徒,他制定了《周期法》 ,创造了元素的元素周期表,并用它来纠正一些已经发现的元素的性质,并预测尚待发现的八种元素的性质。

公元1901-2000年(20世纪)

[编辑]根据100年诺贝尔奖,1901年至2000年间对诺贝尔奖的评论显示,(65.4%)的诺贝尔奖获得者认为基督教的各种形式是他们的宗教偏好。[80] 总的来说,基督徒获得了72.5% 的诺贝尔化学奖,65.3% 的物理学,62% 的医学奖,54% 的经济学奖。[81]

- 约翰 · 霍尔 · 格拉德斯通(1827-1902) : 在1874年至1876年期间担任物理学会主席,1877-1879年担任化学学会主席。 他也属于基督教证据协会。[82][83]

- 乔治 · 斯托克斯(1819-1903) : 部长的儿子,他写了一本关于自然神学的书。 他也是英国皇家学会的主席之一,并为 Fluid dynamics 做出了贡献。[84][85]

- 亨利·贝克·特里斯特拉姆(1822-1906) : 英国鸟类学家联合会创始成员。 他的出版物包括《圣经的自然史》(1867)和《巴勒斯坦的动植物》(1884)。[86]

- 伊诺克 · 费奇 · 伯尔(1818-1907) : 天文学家和公理会牧师,对科学和宗教之间的关系进行了广泛的演讲。 他还在1867年写了 Ecce Coelum: 或 Parish Astronomy。 他曾经说过,"一个不虔诚的天文学家是疯狂的",并且坚信外星生命。[87][88]

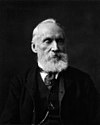

- 开尔文勋爵(1824-1907) : 在格拉斯哥大学期间,他在电力的数学分析和第一和第二热力学定律的制定方面做了重要的工作。 他向基督教证据协会发表了一个著名的演说。 在科学领域,他获得了科普利奖章和皇家勋章。[89]

- 威廉 · 达林格(1839-1909) : 英国卫斯理卫理公会教堂部长,一位杰出的科学家,在显微镜下研究了单细胞生物的完整生命周期。[90]

- 埃米尔·特奥多尔·科赫尔(1941-1917) : 曾任瑞士内科医生及医学研究员,曾因其在甲状腺的生理学、病理学和外科方面的工作而获得了1909年的诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。 科彻是一个笃信宗教的人,同时也是摩拉维亚教会的一部分,Kocher 把他所有的成功和失败归功于上帝。[91]

- J. j. Thomson (1856-1940) : 英国物理学家和诺贝尔物理学奖获得者,被认为是电子的发现和识别; 随着第一个次原子粒子的发现。 他是一个保守但虔诚的英国国教徒。[92][93][94]

- Wilhelm r ntgen (1845-1923)是一位德国工程师和物理学家,他于1895年11月8日发明并探测到了一种波长范围内的电磁辐射,这种波长范围被称为 x 射线或 r ntgen 射线,这一成就为他赢得了1901年的第一个诺贝尔物理学奖[95]

- 朱塞佩·麦加利(1850-1914)是意大利的火山学家和天主教神父。 他以测量地震的麦加利地震烈度而被人们铭记。

- Pierre Duhem (1861-1916) : 研究热力学的潜力,并撰写历史,主张罗马天主教会帮助推进科学。[96][97][98][99][100]

- 詹姆斯 · 布里顿(1846-1924) : 深入参与天主教真理学会的植物学家。[101][102]

- 查尔斯 · 杜利特尔 · 沃尔科特(1850-1927) : 沃尔科特是一位古生物学家,最引人注目的是他发现了 Burgess Shale of British Columbia。 已故的史蒂芬·古尔德说,"Burgess Shale 化石的发现者"沃尔科特是一个被说服的达尔文主义者和一个同样坚定的基督徒,他相信上帝已经按照自己的计划和目的选择自然选择来构建生命的历史。"[103]

- Johannes Reinke (1849-1931) : 德国植物学家和博物学家创立了德国植物学会。 作为达尔文主义和科学世俗化的反对者,他写了 Kritik der abstammunslehre (对进化论的批判) ,(1920年)和自然科学,Weltanschauung,宗教,(科学,哲学,宗教) ,(1923)。 他是一位虔诚的路德教徒。[104]

- 古列尔莫·马可尼(1874-1937) : 意大利发明家和电气工程师,以其在远距离无线电传输和马可尼定律的发展和无线电报系统而闻名。 他分享了1909年的诺贝尔物理学奖。[105][106]

- 德日进: 法国耶稣会古生物学家,北京人的共同发现者,以进化论和基督教著称。 他把欧米茄点假设为进化论的最终目标,他被广泛认为是20世纪最重要的天主教神学家之一。

- 威廉 · 威廉姆斯 · 基恩(1837-1932) : 美国第一位脑外科医生,以及曾担任美国医学会主席的著名外科病理学家。 他还写道: 我相信上帝,相信进化论。[107]

- 弗朗西斯·加文(1875-1937) : 普里斯特里 · 梅德尔(Priestley Medalist)获得了维拉诺瓦大学的"孟德尔奖章",被天主教行动称为"杰出的天主教门外汉",并参与了美国天主教大学。[108][109]

- 帕维尔•弗洛伦斯基(Pavel Florensky,1882-1937) : 俄罗斯东正教牧师写了一本关于恋父情结的书,并写下了与上帝的国度有关的虚数。[110]

- Eberhard Dennert (1861-1942) : 德国博物学家和植物学家创立了开普勒联合会,一群德国知识分子强烈反对哈克尔的单一主义联盟和达尔文的理论。[111] 作为一名路德派教徒,他写道: 达尔文哲学博士是 Vom Sterbelager des Darwinismus,他的名字叫做达尔文主义的临终之处(1904年)。

- 乔治·华盛顿·卡弗: 美国科学家、植物学家、教育家和发明家。 卡佛相信他可以信仰上帝和科学,并将他们融入他的生活。 他在许多场合作证说,他对耶稣的信仰是他能够有效地追求和执行科学艺术的唯一机制。[112]

- 亚瑟·爱丁顿(1882-1944) : 英国20世纪早期的天体物理学家。 他也是一位科学哲学家和科学的普及者。 埃丁顿极限——恒星光度的自然界限,或者由于吸附到一个紧凑的物体上所产生的辐射,都是以他的名字命名的。 他因在相对论方面的工作而出名。 爱丁顿是一个终身贵格会教徒,1927年他成为了教友吉福德的讲述教学法。[113]

- 亚历克西斯 · 卡雷尔(1873-1944) : 法国外科医生和生物学家,因为开创性的血管缝合技术于1912年获得诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。[114]

- 查尔斯·格洛弗·巴克拉(1877-1944) : 英国物理学家,1917年诺贝尔物理学奖得主,因为他在 x 射线研究中的 X射线光谱仪和相关领域的研究成果。[115] 巴克拉先生是一位卫理公会派教徒,他认为自己的工作是对上帝、造物主的追求的一部分。[116][117][118]

- 约翰·安布鲁斯·弗莱明(1849-1945) : 在科学领域,他以右手法则和真空管工作著称。 他还获得了休斯奖章。 在宗教活动中,他是维多利亚学院的主席,并在圣马田教堂布道。[119][120][121]

- 菲利普 · 雷纳德(1862-1947) : 德国物理学家,1905年诺贝尔物理学奖获得者,因为他对阴极射线的研究和他们的许多性质的发现。 他也是纳粹意识形态的积极支持者。[122][123]

- 罗伯特 · 米利肯(1868-1953) : Reverend Silas Franklin Millikan 的次子,他在《科学与宗教的进化》一书中写到了科学与宗教的和解。 他赢得了1923年诺贝尔物理学奖。[124][125][126][127][128]

- 卡尔·兰德施泰纳(1868-1943) : 曾任奥地利生物学家、医生和免疫学家。[129] 1930年,他收到了诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。 1890年,兰德斯坦从犹太教转变为罗马天主教。[130]

- 查尔斯 · 斯坦(1882-1954) : 杜邦公司副总裁的儿子。 在宗教方面,他写了一本《化学家与他的圣经》 ,作为一名化学家,他赢得了 Perkin 奖章。[131]

- 马克斯 · 波恩(1882-1970) : 是一位德国物理学家和数学家,他在量子力学的发展中起到了重要作用。 出生于1954年诺贝尔物理学奖,因为他"对量子力学的基础研究,尤其是对波函数的统计解释"而获得诺贝尔物理学奖[132][133][134]

- E.t. 惠特克(1873-1956) : 1930年皈依天主教,成为宗座科学科学院会员。 他1946年的唐奈伦演讲题为《空间与精神》。 宇宙理论与上帝存在论。 他还获得了科普利奖章,并在转化前写过数学物理。[135]

- 亚瑟 · 康普顿(1892-1962) : 获得诺贝尔物理学奖。 他还是浸礼会教堂的执事,在《基督教采取立场》中写了一篇文章,支持美国通过一支拥有核武器的空军维持和平的有争议的想法。[136][137]

- 维克托·赫斯(1883-1964) : 练习罗马天主教,他获得了诺贝尔物理学奖,并发现了宇宙射线。[138] 1946年,他在《我的信仰》一文中就科学与宗教之间的关系这一主题写了一篇文章,其中他解释了为什么他相信上帝。[139]

- 罗纳德 · 费舍尔(1890-1962) : 英国统计学家、进化生物学家和遗传学家。 他在教会杂志上布道和发表文章。[140]

- 乔治·勒梅特(1894-1966) : 罗马天主教牧师,他第一次提出了宇宙大爆炸理论。[141]

- 凯瑟琳·朗斯代尔(1903-1971) : 著名的爱尔兰晶体学家,伦敦大学学院第一位女性终身教授,国际晶体学联合会的第一位女性主席,以及第一位女性英国科学协会主席。 她皈依了 Quakerism,是一个积极的基督教和平主义者。 她是教会治疗委员会的第一个秘书,并且发表了一份斯沃斯莫尔讲座。

- 尼尔·肯辛顿·阿当(1891-1973) : 撰写这篇文章的英国化学家基督教科学家研究自然科学的方法。[142][143]

- 大卫 · 拉克(1910-1973) : 爱德华 · 格雷野外鸟类学研究所所长,部分以研究优生属而闻名。 他在38岁时皈依了英国国教,并在1957年写下了进化论和基督教信仰。[144][145]

- 休 · 斯托特 · 泰勒(1910-1974) : 化学家获得了维拉诺瓦大学的"孟德尔奖章",并被任命为教皇圣格雷戈瑞勋章骑士指挥官。[146][147]

- 查尔斯 · 库尔森(1910-1974) : 1955年写科学与基督教信仰的卫理公会派教徒。 1970年,他获得了戴维奖章。[148]

- 乔治 · r · 普莱斯(1922-1975) : 美国人口遗传学家,一个强大的无神论者皈依了基督教。 他继续写关于《新约》的评论,并致力于帮助穷人。[149]

- 费奥多西·多布然斯基(1900-1975) : 俄罗斯东正教遗传学家在一篇文章中批评年轻地球创造论,"除了进化论之外,生物学中没有什么是有意义的",并且认为科学和信仰并不冲突。[150][151]

- 维尔纳·海森堡(1901-1976) : 德国理论物理学家,量子力学的开拓者之一。 1932年,海森堡因"创造量子力学"而获得诺贝尔物理学奖。[152]

- 迈克尔 · 波兰尼(1891-1976): 出生于犹太人,后来成为基督徒。 1926年,他被任命为柏林的化学主席,但在1933年希特勒上台时,他接受了一把化学椅(1948年,他在曼彻斯特大学担任社会科学主席)。 1946年,他写了《科学,信仰和社会》 ,ISBN 0-226-67290-5。[153]

- 沃纳·冯·布劳恩(1912-1977) :"20世纪30年代至70年代期间,最重要的火箭开发者和太空探索的冠军之一。"[154] 他是一个路德教徒,他年轻时对宗教不感兴趣。 但是作为一个成年人,他对上帝和来世有着坚定的信仰。 他很高兴有机会与同龄人(以及任何愿意倾听的人)谈论他的信仰和圣经信仰。[155]

- 帕斯夸尔 · 乔丹(1902-1980) : 德国理论和数学物理学家,他对量子力学和量子场论做出了重大贡献。 他对矩阵力学的数学形式做出了很大贡献,并且发展了费米子的规范减刑关系。[156][157]

- 彼得 · 斯通纳(1888-1980) : 美国科学联盟的共同创始人,他写了《科学讲话》。[158][159]

- 1896-1957年: 捷克裔美国生物化学家,成为第三位女性,也是第一位获得诺贝尔科学奖的美国女性,也是第一位获得诺贝尔科学奖的美国女性,也是第一位获得诺贝尔科学奖的女性。 戈蒂皈依了天主教。[160][161]

- 亨利 · 艾林(1901-1981) : 美国化学家,以开发艾林方程而闻名。 也是后一天的圣人,他与身份证总裁约瑟夫 · 菲尔丁 · 史密斯在科学和信仰方面的互动是 LDS 历史的一部分。[162][163]

- 玛丽 · 肯尼思 · 凯勒(1914-1985) : 美国修女,她是美国第一位获得计算机科学博士学位的女性。[164]

- 威廉 · g · 波拉德(1911-1989) : 《物理学家与基督徒》的作者,英国圣公会牧师。 此外,他在曼哈顿项目工作,多年来担任橡树岭核研究所执行主任。[165]

- 弗雷德里克·罗西尼(1899-1990) : 美国人以其在化学热力学方面的工作而闻名。 在科学领域,他获得了 Priestley 奖章和美国国家科学奖章。 第二枚奖牌的一个例子。 作为一名天主教徒,他获得了拉蒂尔圣母大学勋章。 他是巴黎圣母院的科学院院长,从1960年到1971年,他可能已经采取了部分由于他的信仰。[166][167]

- Aldert van der Ziel (1910-1991) : 研究闪烁噪声,并让电气和电子工程师协会为他颁发了一个奖项。 他也是一个保守的路德教派,他写了《自然科学》和《基督教信息》。[168]

- J r me Lejeune (1926-1994) : 法国儿科医生和遗传学家,以研究染色体异常,特别是唐氏综合症而闻名。 他是宗座生命学院的第一任总统,并被任命为"上帝的仆人"[169][170]

- 阿隆索 · 丘奇(1903-1995) : 美国数学家和逻辑学家,他对数学逻辑和理论计算机科学的基础做出了重大贡献。 他是长老会教会的终身成员。[171]

- 欧内斯特 · 沃尔顿(1903-1995) : 爱尔兰物理学家,1951年因为与约翰 · 考克罗夫特的合作获得了诺贝尔物理学奖,并于1930年代初在剑桥大学进行了"原子破碎"实验,并因此成为历史上第一个人为地分裂原子,从而开创了核时代。 他讲科学和信仰的话题。[172]

- 内维尔·莫特(1905-1996) : 英国圣公会是一位获得诺贝尔奖的物理学家,以解释光线对感光乳剂的影响而闻名。[173] 他在80岁时接受了洗礼,并编辑了《科学家能相信吗?.[174]

- Mary Celine Fasenmyer (1906-1996) : 慈善修女会成员,以席琳修女的多项式而著称。 她的工作对 WZ 理论也很重要。[175]

- 约翰 · 埃克尔斯(1903-1997) : 诺贝尔奖获得者和神经生理学家,他是一位虔诚的神学家和一位虔诚的天主教徒。[176]

- 阿瑟·肖洛(1921-1999) : 阿瑟 · 肖洛是一位美国物理学家,他最为人们所记得的是他在激光方面的工作,他曾获得1981年诺贝尔物理学奖。 肖洛是一个"正统的精灵新教徒"[177] 在一次采访中,他评论了上帝:"我发现在宇宙和我自己的生命中需要上帝。"[178]

- 卡洛斯 · 查加斯 · 费罗(1910-2000) : 16年来领导宗座科学科学院的神经科学家。 他研究了都灵的裹尸布和他的"宇宙起源","生命的起源",和"人的起源"涉及天主教与科学之间的一种理解。 他来自里约热内卢。[179]

二零零一年至今(二十一世纪)

[编辑]- 罗伯特 · 博伊德爵士(1922-2004) : 英国空间科学先驱,英国皇家天文学会副总裁。 他讲信仰是"研究科学家基督徒团契"的创始人,也是其前身科学基督徒的重要成员。[180]

- Richard h. Bube (1927-2018) : 斯坦福大学材料科学名誉教授。 他是美国科学联盟的成员。[181]

- 罗德 · 戴维斯(1930-2015) : 曼彻斯特大学射电天文学教授。 他于一九八七至一九八九年担任英国皇家天文学会总裁,一九八八至九七年担任卓瑞尔河岸天文台总监。 他最出名的是他对宇宙微波背景和21厘米线的研究。

- 阿尔贝托 · 窦 · 马斯 · 德 · 赛克斯(1915-2009) : 西班牙 / 加泰罗尼亚耶稣会牧师,他的国家最重要的数学家之一。 他是皇家科学院的一名成员,也是马德里康普顿斯大学的数学教授,1974年至1977年担任德乌斯托大学校长。

- 理查德 · 斯莫利(1943-2005) : 诺贝尔化学奖得主,以鹿球闻名。 在他的最后几年,他重申了对基督教的兴趣,并支持了旧地球神创论

- 马里亚诺 Artigas (1938-2006) : 他拥有物理学和哲学双学位。 他是欧洲科学和神学研究协会的成员,也因其在科学和宗教领域的工作而获得 Templeton 基金会的一笔赠款。[182]

- J. Laurence Kulp (1921-2006) : 主持核辐射和酸雨影响的主要研究的普利茅斯弟兄会。 他是美国科学联盟的杰出倡导者,支持旧地球和洪水地质学。[183][184][185][186]

- 阿瑟 · 皮科克(1924-2006) : 英国圣公会的牧师和生物化学家,他的思想可能影响了英国圣公会和路德派对进化论的看法。 2001年邓普顿奖得主[187]

- 约翰 · 比林斯(1918-2007) : 澳大利亚医生,开发了自然计划生育的比林斯排卵法。 1969年,毕林斯被教皇保罗六世任命为圣格雷戈瑞勋章的骑士指挥官。[188]

- 拉塞尔 · l · 米斯特尔(1906-2007) : 以领导美国科学联盟(ASA)远离反进化论,并倡导进步的神创论。[189]

- 冯 · 魏茨 · 科尔(1912-2007) : 德国核物理学家,他是贝斯-魏茨公式的共同发现者。 他的《科学的相关性: 创造与宇宙论》涉及科学对基督教和道德的影响。 他从1970年到1980年担任马克斯·普朗克学会主席。 之后,他退休成为一名基督教和平主义者。[190]

- 斯坦利 · 贾基(1924-2009) : 新泽西州薛顿贺尔大学的本笃会牧师和物理学杰出教授,他获得了邓普顿奖,并主张现代科学只能出现在基督教社会的观点。[191]

- Allansandage (1926-2010) : 四十岁以后才真正学习基督教的天文学家。 他写了一篇《科学家反思宗教信仰》的文章,并对雪茄星系有了新的发现。[192][193][194][195]

- Ernan McMullin (1924-2011) : 麦克穆林于1949年被任命为天主教牧师,麦克穆林是一位科学哲学家,在圣母大学教书。 麦克穆林在《牛顿物质与活动》(1978)和《科学的推论》(1992)等书中,麦克穆林写了宇宙学和神学之间的关系,价值观在理解科学方面的作用,以及科学对西方宗教思想的影响。 他也是伽利略生活方面的专家。[196] 麦克穆林还反对智能设计和防御神导演化论。[197]

- Joseph Murray (1919-2012) : 首创移植手术的天主教外科医生。 他在1990年赢得了诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。[198]

- 伊恩 · 巴伯(1923-2013年) : 1960年写过基督教和科学家的物理学家,以及2000年《科学与宗教》的结合。[199]

- 查尔斯 · h · 托恩斯(1915-2015) : 1964年,他获得了诺贝尔物理学奖,1966年他写了《科学与宗教的融合》。[200][201]

- 彼得 · e · 霍奇森(1928-2008) : 英国物理学家,是最早确定 k 介子及其衰变为三个介子的物理学家之一,也是宗座文化理事会的顾问。

- Nicola Cabibbo (1935-2010) : 意大利物理学家,弱相互作用的普遍性的发现者(Cabibbo 角度) ,1993年至死亡宗座科学科学院的总统。

- 沃尔特 · 瑟林(1927年至2014年) : 奥地利物理学家,在量子场论中命名了 Thirring 模型。 他是物理学家汉斯 · 瑟林(Hans Thirring)的儿子,同时也是 lense-Thirring 框架拖曳效应的广义相对论。 他还写了《宇宙印象: 自然法则中的上帝的痕迹》。[202]

- 彼得 · 格林伯格(1939-2018年) : 德国物理学家,诺贝尔物理学奖得主,因为他与阿尔伯特 · 费尔特一起发现了千兆字节硬盘驱动器的突破[203]

- R. j. Berry (1934-2018): 伦敦林奈学会和"科学中的基督徒"组织的前任主席。 他写了《上帝与生物学家: 科学与信仰的个人探索》(Apollos 1996) ISBN 0-85111-446-6他在伦敦大学学院教了20多年。[204][205]

在世

[编辑]生物和生医科学

[编辑]- 费里德 · 穆拉德(1936年出生)是一名医生和药理学家,也是1998年诺贝尔生理学或医学奖的共同获奖者。 他是作为基督徒长大的。[206]

- 丹尼斯 · 亚历山大(出生于1945年) : 剑桥大学法拉第研究所荣誉主任,《重建21世纪的矩阵ー科学与信仰》一书的作者。 他还在巴布拉汉姆研究所监督一个癌症和免疫学研究小组。[207]

- 沃纳 · 阿伯(1929年出生) : 瑞士微生物学家和遗传学家。 他和美国研究人员汉密尔顿 · 史密斯和丹尼尔 · 纳斯恩一起分享了1978年发现限制性内切酶的诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。 2011年,本笃十六世任命阿伯为教皇学院院长,这是第一个担任这一职务的新教徒。[208]

- 罗伯特·巴克(出生于1945年) : 古生物学家是"恐龙文艺复兴"中的领军人物,他以一些恐龙是温血动物而闻名。 他也是一位五旬节教派的传教士,他提倡宗教神导演化论,并撰写有关宗教的著作。[209][210]

- 丹 · 布雷泽(生于1944年) : 美国精神病学家和医学研究者,杜克大学医学院精神病学和行为科学教授。 他以研究抑郁症的流行病学、物质使用障碍和老年人自杀的发生而闻名。 他还研究了种族间物质使用障碍率的差异。[211]

- 德里克 · 伯克(出生于1930年) : 英国学者和分子生物学家。 曾任东英吉利亚大学副校长。 自一九八五年起担任英国下议院科学及科技专责委员会专家顾问。

- 威廉·塞西尔·坎贝尔(生于1930年) : 爱尔兰裔美国生物学家和寄生虫学家,因为他致力于发现一种新的治疗蛔虫感染的新方法,为此他共同获得了2015年的诺贝尔生理学或医学奖[212]

- 本 · 卡森(1951年出生) : 美国神经外科医生。 第一对成功分离的连体双胞胎头部相连。[213]

- 弗朗西斯 · 柯林斯(生于1950年) : 美国国家人类基因组研究所(US National Human Genome Research Institute)前所长。 他还在文章和《上帝的语言: 科学家为信仰提供证据》一书中就宗教问题写过文章。[214][215]

- 彼得 · 道森(彼得 · 道森,1946年出生) : 美国古生物学家,他发表了许多论文,并撰写和合作了有关恐龙的书籍。 他还是《恐龙》杂志的联合编辑,也撰写了几篇关于黑龙江和蜥脚类动物的论文和教科书,同时还是《恐龙》的联合编辑。 他是脊椎动物古生物学和兽医解剖学的宾夕法尼亚大学教授。

- 林登 · 伊维斯(1944年出生) : 英国行为遗传学家,出版了关于宗教和精神病理学的遗传性这样多种多样的主题。 1996年,他和肯尼斯 · 肯德勒在弗吉尼亚联邦大学成立了弗吉尼亚精神病学和行为遗传学研究所,目前他在那里从事名誉教授研究和培训工作。[216][217]

- 达雷尔 · r · 福尔克(1946年出生) : 美国生物学家,生物标志基金会前主席。[218]

- 凯文 · 菲茨杰拉德(1955 -) : 美国分子生物学家,在天主教保健伦理学中担任大卫 · 劳勒博士的乔治城大学

- 查尔斯 · 福斯特(1962年出生) : 自然历史、进化生物学和神学的科学作家。 作为牛津大学格林坦普顿学院、牛津、皇家地理学会和伦敦林奈学会的研究员,福斯特在他的著作《无私的基因》(The untiess Gene,2009)中提倡神导演化论。[219][220]

- 约翰 · 格登(1933年出生) : 英国发展生物学家。 2012年,他和山中伸弥(Shinya Yamanaka)因发现成熟细胞可转化为干细胞而被授予诺贝尔生理学或医学奖。 在接受 EWTN.com 的采访时,他说:"我不是罗马天主教徒。 我是英国教会的基督徒。..我以前从未见过梵蒂冈,所以这是一次新的经历,我很感激。"[221]

- 布莱恩 · 希普(生于1935年) : 生物学家,剑桥大学圣埃德蒙学院的院长,是国际科学与宗教学会的创始成员。[222][223]

- 威廉 · b · 赫尔特: 斯坦福大学医学中心斯坦福神经科学研究所的医生兼顾问教授。 他在总统生物伦理委员会任职8年,并以倡导改变核转移(ANT)闻名全国。 他是一个没有教派的基督徒,在斯坦福大学读了三年神学和医学伦理学博士后研究。[224][225]

- 马尔科姆 · 吉夫斯(诞生于1926年) : 英国神经心理学家,圣安德鲁斯大学的心理学名誉教授,以前是爱丁堡皇家学会的主席。 他在圣安德鲁斯大学设立了心理学系。[226]

- 拉里 · 夸克(出生于1959年) : 美国著名癌症研究员,在希望市国家医疗中心工作。 他曾任淋巴瘤和骨髓瘤部的主任,同时也是癌症免疫学研究中心的德州大学安德森癌症中心主任。[227] 他被《时代》杂志评为2010年最有影响力人物的名单。

- Denis Lamoureux (1954年出生) : 进化论创世论。 他在加拿大圣约瑟夫学院(st. Joseph's College)担任科学和宗教教授,这是加拿大首次举办此类活动。 共同写作(菲力普·约翰逊)达尔文主义失败? 关于生物起源的 Johnson-Lamoureux 辩论(1999年)。 《进化创造: 基督教进化论》(2008)。[228]

- 诺拉 · 马塞利诺(1951年出生) : 美国本笃会修女,拥有微生物学学位。 她的兴趣领域包括真菌和腐烂和腐烂的影响。[229]

- 保罗 · r · 麦克休(1931年出生) : 美国精神病学家,他的研究主要集中在动机行为、精神遗传学、流行病学和神经精神病学的神经科学基础。 他是约翰·霍普金斯大学医学院的精神病学和行为科学教授,曾任约翰·霍普金斯医院精神病学主任。

- 肯尼斯 · r · 米勒(1948年出生): 布朗大学的分子生物学家,他写了《发现达尔文的上帝》 ,ISBN 0-06-093049-7。[230]

- 西蒙 · 莫里斯(出生于1951年) : 英国古生物学家和进化生物学家,通过研究 Burgess Shale 化石而声名远扬。 自1995年以来,他一直担任剑桥大学地球科学系进化古生物学的主席。 他是查尔斯 · 杜利特尔 · 沃尔科特奖章的共同获得者,同时还获得了一枚莱尔奖章。 他在法拉第科学和宗教研究所积极工作,并在讨论神导演化论的问题上也受到注意。[231][232][233]

- 威廉 · 纽森(1952年出生) : 斯坦福大学的神经科学家。 美国国家科学院院士。 Brain Initiative 的联席主席,"对大脑工作方式进行十年突击的快速规划工作"[234] 他曾写过他的信仰:"当我和我的科学家同事讨论宗教问题时。..我意识到我是一个怪人ーー一个严肃的基督徒和受人尊敬的科学家."[235]

- 马丁 · 诺瓦克(1965年出生) : 进化生物学家和数学家,以进化动力学著称。 他在哈佛大学任教,同时也是邓普顿基金会顾问委员会的成员。[236][237]

- Bennet Omalu (1968年出生) : 一位尼日利亚裔美国人的医生、法医病理学家和神经病理学家,他是第一个发现并公布美国足球运动员 CTE 的发现。 他是加州大学戴维斯分校医学病理学和实验医学系的教授。[238]

- Tadeusz Pacholczyk (1965 -) : 牧师,神经生物学家,作家

- Ghillean Prance (1937年出生) : 植物学家参与了伊甸园计划。 他是前基督教科学会主席。[239]

- 乔娜·拉夫加登(生于1946年) : 1972年开始在斯坦福大学任教的进化生物学家。 她写了一本书《进化论与基督教信仰: 进化生物学家的反思》。[240]

- Mary Higby Schweitzer: 北卡罗来纳州立大学的古生物学家,相信基督教信仰和经验科学真理的协同作用。[241][242]

- 安德鲁 · 威利: 苏格兰病理学家,他发现了自然细胞死亡的重要性,后来将其命名为细胞凋亡。 退休前,他是剑桥大学病理学系系主任。[243]

化学

[编辑]- 彼得 · 阿格尔(生于1949年1月30日) : 美国内科医生,彭博杰出教授,约翰·霍普金斯大学分子生物学家,因发现水瓶座而获得2003年诺贝尔化学奖(他与罗德里克·麦金农共享)。 阿格雷是一位路德教徒。[244]

- Andrew b. Bocarsly (1954年出生) : 美国化学家,以研究电化学、光化学、固体化学和燃料电池而闻名。 他是普林斯顿大学的化学教授。[245]

- 格哈德 · 厄特尔(1936年出生) : 2007年诺贝尔化学奖得主。 他在一次采访中说:"我相信上帝。 (...我是一个基督徒,我试图像一个基督徒那样生活。..我经常读圣经,我试着去理解它。"[246]

- 布莱恩 · 科比尔卡(生于1955年) : 2012年美国诺贝尔化学奖得主,斯坦福大学医学院分子和细胞生理学系教授。 科比尔卡在加利福尼亚州斯坦福市参加天主教社区。[247] 他从维拉诺瓦大学中获得孟德尔奖章,称这是为了表彰杰出的先锋科学家,他们以他们的生活和作为科学家在世界上的地位证明了科学和宗教之间没有内在的冲突。"[248]

- 托德 · 马丁内斯(1968年生) : 美国理论化学家,斯坦福大学化学教授,SLAC 国家加速器实验室光子科学教授。 他的研究主要集中在开发化学反应动态学的第一原则方法上,从量子力学的基本方程出发。[249]

- 亨利 · f · 谢弗,三世(1944年出生)美国计算和理论化学家,世界上被引用最多的科学家之一,汤森路透 h 指数为116。 他是格雷厄姆•佩尔杜(Graham Perdue)化学教授、佐治亚大学计算化学中心主任。[250]

- 詹姆斯 · 图尔(1959年出生) : 德克萨斯州莱斯大学化学教授,在那里他还担任计算机科学和材料方面的教师任命; 被公认为世界领先的纳米工程师之一。 获得了普渡大学合成有机和有机金属化学的博士学位,并在威斯康星大学麦迪逊分校和斯坦福大学接受了合成有机化学的博士后培训。 作为一名福音派基督徒,杜尔写道:"我以构建分子为生,我无法告诉你这份工作有多困难。 我站在神的敬畏之下,因为他在创造过程中所做的一切。 只有一个对科学一无所知的新手才会说科学会夺走信仰。 如果你真的学习科学,它会让你更接近上帝。"[251]

- 特洛伊 · 范沃尔赫: 美国化学家,现任麻省理工学院哈斯拉姆和杜威化学教授。[252]

- 约翰 · 怀特(化学家) : 著名的澳大利亚化学家,现任澳大利亚国立大学化学研究学院物理和理论化学教授。 他是澳大利亚皇家化学研究所前任主席和澳大利亚核科学与工程研究所所长。[253]

物理学和天文学

[编辑]- Freeman Dyson (born 1923): English-born American theoretical physicist and mathematician, known for his work in quantum electrodynamics, solid-state physics, astronomy and nuclear engineering.

- Stephen Barr (born 1953): physicist who worked at Brookhaven National Laboratory and contributed papers to Physical Review as well as Physics Today. He also is a Catholic who writes for First Things and wrote Modern Physics and Ancient Faith. He teaches at the University of Delaware.[254]

- John D. Barrow (born 1952): English cosmologist based at the University of Cambridge who did notable writing on the implications of the Anthropic principle. He is a United Reformed Church member and won the Templeton Prize in 2006. He once held the position of Gresham Professor of Astronomy as well as Gresham Professor of Geometry.[255][256]

- Jocelyn Bell Burnell (born 1943): an astrophysicist from Northern Ireland who discovered the first radio pulsars in 1967. She is currently Visiting Professor of Astrophysics at the University of Oxford.

- Arnold O. Benz (born 1945): Swiss astrophysicist, currently professor emeritus at ETH Zurich. He is known for his research in plasma astrophysics,[257] in particular heliophysics, and received honorary doctoral degrees from the University of Zurich and The University of the South for his contributions to the dialog with theology.[258][259]

- Katherine Blundell: British astrophysicist who is a Professor of Astrophysics at the University of Oxford and a supernumerary research fellow at St John's College, Oxford. Her research investigates the physics of active galaxies such as quasars and objects in the Milky Way such as microquasars.[260]

- Stephen Blundell (born 1967): British physicist who is a Professor of Physics at the University of Oxford. He was the previously head of Condensed Matter Physics at Oxford. His research is concerned with using muon-spin rotation and magnetoresistance techniques to study a range of organic and inorganic materials.[261]

- Andrew Briggs (born 1950): British scientist who is Professor of Nanomaterials at the University of Oxford. He is best known for his early work in acoustic microscopy and his current work in materials for quantum technologies.[262][263]

- Raymond Chiao (born 1940): American physicist renowned for his experimental work in quantum optics. He is currently an emeritus faculty member at the University of California, Merced Physics Department, where he is conducting research on gravitational radiation.[264][265]

- Gerald B. Cleaver: professor in the Department of Physics at Baylor University and head of the Early Universe Cosmology and Strings (EUCOS) division of Baylor's Center for Astrophysics, Space Physics & Engineering Research (CASPER). His research specialty is string phenomenology and string model building. He is linked to BioLogos and among his lectures are ""Faith and the New Cosmology."[266][267]

- Guy Consolmagno (born 1952): American Jesuit astronomer who works at the Vatican Observatory.

- George Coyne (born 1933): Jesuit astronomer and former director of the Vatican Observatory.

- Cees Dekker (born 1959): Dutch physicist and Distinguished University Professor at the Technical University of Delft. He is known for his research on carbon nanotubes, single-molecule biophysics, and nanobiology. Ten of his group publications have been cited more than 1000 times, 64 papers got cited more than 100 times, and in 2001, his group work was selected as "breakthrough of the year" by the journal Science.[268]

- Manuel García Doncel (born 1930): Spanish Jesuit physicist, formerly Professor of Physics at Universidad de Barcelona.

- George Francis Rayner Ellis (born 1939): professor of Complex Systems in the Department of Mathematics and Applied Mathematics at the University of Cape Town in South Africa. He co-authored The Large Scale Structure of Space-Time with University of Cambridge physicist Stephen Hawking, published in 1973, and is considered one of the world's leading theorists in cosmology. He is an active Quaker and in 2004 he won the Templeton Prize.

- Gerald Gabrielse (born 1951): American physicist renowned for his work on anti-matter. He is the George Vasmer Leverett Professor of Physics at Harvard University, incoming Board of Trustees Professor of Physics and Director of the Center for Fundamental Physics at Low Energy at Northwestern University.[269][270]

- Pamela L. Gay (born 1973): American astronomer, educator and writer, best known for her work in astronomical podcasting. Doctor Gay received her PhD from the University of Texas, Austin, in 2002.[271] Her position as both a skeptic and Christian has been noted upon.[272]

- Karl W. Giberson (born 1957): Canadian physicist and evangelical, formerly a physics professor at Eastern Nazarene College in Massachusetts, Giberson is a prolific author specializing in the creation-evolution debate and who formerly served as vice president of the BioLogos Foundation.[273] He has published several books on the relationship between science and religion, such as The Language of Science and Faith: Straight Answers to Genuine Questions and Saving Darwin: How to be a Christian and Believe in Evolution.

- Owen Gingerich (born 1930): Mennonite astronomer who went to Goshen College and Harvard. He is Professor Emeritus of Astronomy and of the History of Science at Harvard University and Senior Astronomer Emeritus at the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory. Mr. Gingerich has written about people of faith in science history.[274][275]

- J. Richard Gott (born 1947): professor of astrophysical sciences at Princeton University. He is known for developing and advocating two cosmological theories with the flavor of science fiction: Time travel and the Doomsday argument. When asked of his religious views in relation to his science, Gott responded that "I’m a Presbyterian. I believe in God; I always thought that was the humble position to take. I like what Einstein said: "God is subtle but not malicious." I think if you want to know how the universe started, that's a legitimate question for physics. But if you want to know why it's here, then you may have to know—to borrow Stephen Hawking's phrase—the mind of God."[276]

- Monica Grady (born 1958): leading British space scientist, primarily known for her work on meteorites. She is currently Professor of Planetary and Space Science at the Open University.

- Robert Griffiths (born 1937): noted American physicist at Carnegie Mellon University. He has written on matters of science and religion.[277]

- Frank Haig (1928–): American physics professor

- John Hartnett (born 1952): Australian Young Earth Creationist who has a PhD and whose research interests include ultra low-noise radar and ultra high stability cryogenic microwave oscillators.[278][279][280]

- Daniel E. Hastings: American physicist renowned for his contributions in spacecraft and space system-environment interactions, space system architecture, and leadership in aerospace research and education.[281] He is currently the Cecil and Ida Green Education Professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.[282]

- Michał Heller (born 1936): Catholic priest, a member of the Pontifical Academy of Theology, a founding member of the International Society for Science and Religion. He also is a mathematical physicist who has written articles on relativistic physics and Noncommutative geometry. His cross-disciplinary book Creative Tension: Essays on Science and Religion came out in 2003. For this work he won a Templeton Prize.[note 6][283]

- Antony Hewish (born 1924): British Radio Astronomer who won the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1974 (together with Martin Ryle) for his work on the development of radio aperture synthesis and its role in the discovery of pulsars. He was also awarded the Eddington Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1969. Hewish is a Christian.[284] Hewish also wrote in his introduction to John Polkinghorne's 2009 Questions of Truth, "The ghostly presence of virtual particles defies rational common sense and is non-intuitive for those unacquainted with physics. Religious belief in God, and Christian belief ... may seem strange to common-sense thinking. But when the most elementary physical things behave in this way, we should be prepared to accept that the deepest aspects of our existence go beyond our common-sense understanding."[285]

- Joseph Hooton Taylor Jr. (born 1941): American astrophysicist and Nobel Prize laureate in Physics for his discovery with Russell Alan Hulse of a "new type of pulsar, a discovery that has opened up new possibilities for the study of gravitation." He was the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor in Physics at Princeton University.[286]

- John T. Houghton (born 1931): British atmospheric physicist who was the co-chair of the Nobel Peace Prize winning Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's (IPCC) scientific assessment working group. He was professor in atmospheric physics at the University of Oxford and former Director General at the Met Office.

- Colin Humphreys (born 1941): British physicist. He is the former Goldsmiths’ Professor of Materials Science and a current Director of Research at the University of Cambridge, Professor of Experimental Physics at the Royal Institution in London and a Fellow of Selwyn College, Cambridge. Humphreys also "studies the Bible when not pursuing his day-job as a materials scientist."[287]

- Ian Hutchinson (scientist): physicist and nuclear engineer. He is currently Professor of Nuclear Science and Engineering at the Plasma Science and Fusion Center, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- Christopher Isham (born 1944): theoretical physicist who developed HPO formalism. He teaches at Imperial College London. In addition to being a physicist, he is a philosopher and theologian.[288][289]

- Stephen R. Kane (born 1973): Australian astrophysicist who specializes in exoplanetary science. He is a professor of Astronomy and Planetary Astrophysics at the University of California, Riverside and a leading expert on the topic of planetary habitability and the habitable zone of planetary systems.[290][291]

- Ard Louis: Professor in Theoretical Physics at the University of Oxford. Prior to his post at Oxford he taught Theoretical Chemistry at the University of Cambridge where he was also director of studies in Natural Sciences at Hughes Hall. He has written for The BioLogos Forum.[292]

- Jonathan Lunine (born 1959): American planetary scientist and physicist, and the David C. Duncan Professor in the Physical Sciences and Director of the Center for Radiophysics and Space Research at Cornell University.[293]

- Juan Maldacena (born 1968): Argentine theoretical physicist and string theorist, best known for the most reliable realization of the holographic principle – the AdS/CFT correspondence.[294] He is a professor at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey and in 2016 became the first Carl P. Feinberg Professor of Theoretical Physics in the Institute's School of Natural Sciences.

- Ross H. McKenzie (born 1960): Australian physicist who is Professor of Physics at the University of Queensland. From 2008 to 2012 he held an Australian Professorial Fellowship from the Australian Research Council. He works on quantum many-body theory of complex materials ranging from organic superconductors to biomolecules to rare-earth oxide catalysts.[295]

- Tom McLeish (born 1962): a theoretical physicist whose work is renowned for increasing our understanding of the properties of soft matter. He was Professor in the Durham University Department of Physics and Director of the Durham Centre for Soft Matter. He is now the first Chair of Natural Philosophy at the University of York.[296]

- Charles W. Misner (born 1932): American physicist and one of the authors of Gravitation. His work has provided early foundations for studies of quantum gravity and numerical relativity. He is Professor Emeritus of Physics at the University of Maryland.[297]

- Barth Netterfield (born 1968): Canadian astrophysicist and Professor in the Department of Astronomy and the Department of Physics at the University of Toronto.[298]

- Don Page (born 1948):[299] Canadian theoretical physicist and practicing Evangelical Christian, Page is known for having published several journal articles with Stephen Hawking.[300][301]

- William Daniel Phillips (born 1948): 1997 Nobel Prize laureate in Physics (1997) who is a founding member of The International Society for Science and Religion.[302]

- Karin Öberg (born 1982): Swedish astrochemist,[303] professor of Astronomy at Harvard University and leader of the Öberg Astrochemistry Group at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics.[304]

- Andrew Pinsent (born 1966): Catholic priest, is the Research Director of the Ian Ramsey Centre for Science and Religion at the University of Oxford.[305] He is also a particle physicist, whose previous work contributed to the DELPHI experiment at CERN.[306]

- John Polkinghorne (born 1930): British particle physicist and Anglican priest who wrote Science and the Trinity (2004) ISBN 0-300-10445-6. He was professor of mathematical physics at the University of Cambridge prior to becoming a priest. Winner of the 2002 Templeton Prize.[307]

- Hugh Ross (born 1945): Canadian astrophysicist, Christian apologist, and old Earth creationist whose postdoctoral research at Caltech was in studying quasars and galaxies.

- Marlan Scully (born 1939): American physicist best known for his work in theoretical quantum optics. He is a professor at Texas A&M University and Princeton University. Additionally, in 2012 he developed a lab at the Baylor Research and Innovation Collaborative in Waco, Texas.[308]

- Russell Stannard (born 1931): British particle physicist who has written several books on the relationship between religion and science, such as Science and the Renewal of Belief, Grounds for Reasonable Belief and Doing Away With God?.[309]

- Andrew Steane: British physicist who is Professor of Physics at the University of Oxford. His major works to date are on error correction in quantum information processing, including Steane codes. He was awarded the Maxwell Medal and Prize of the Institute of Physics in 2000.[310]

- Jeffery Lewis Tallon (born 1948): New Zealand physicist specializing in high-temperature superconductors. He was awarded the Rutherford Medal,[311] the highest award in New Zealand science. In the 2009 Queen's Birthday Honours he was appointed a Companion of the New Zealand Order of Merit for services to science.[312]

- Frank J. Tipler (born 1947): mathematical physicist and cosmologist, holding a joint appointment in the Departments of Mathematics and Physics at Tulane University. Tipler has authored books and papers on the Omega Point, which he claims is a mechanism for the resurrection of the dead. His theological and scientific theorizing are not without controversy, but he has some supporters; for instance, Christian theologian Wolfhart Pannenberg has defended his theology,[313] and physicist David Deutsch has incorporated Tipler's idea of an Omega Point.[314]

- Daniel C. Tsui (born 1939): Chinese-born American physicist whose areas of research included electrical properties of thin films and microstructures of semiconductors and solid-state physics. In 1998 Tsui was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics for his contributions to the discovery of the fractional quantum Hall effect. He was the Arthur LeGrand Doty Professor of Electrical Engineering at Princeton University.[315]

- Rogier Windhorst (born 1955): Dutch astrophysicist who is Foundation Professor of Astrophysics at Arizona State University and Co-Director of the ASU Cosmology Initiative. He is one of the six Interdisciplinary Scientists worldwide for the James Webb Space Telescope, and member of the JWST Flight Science Working Group.

- Jennifer Wiseman: Chief of the Laboratory for Exoplanets and Stellar Astrophysics at NASA Goddard Space Flight Center. An aerial of the Center is shown. In addition she is a co-discoverer of 114P/Wiseman-Skiff. In religion is a Fellow of the American Scientific Affiliation and on June 16, 2010 became the new director for the American Association for the Advancement of Science's Dialogue on Science, Ethics, and Religion.[316]

- Antonino Zichichi (born 1929): Italian nuclear physicist and former President of the Istituto Nazionale di Fisica Nucleare. He has worked with the Vatican on relations between the Church and Science.[317][318]

地球科学

[编辑]- 马丁 · 博特(出生于1926年) : 英国地质学家,现任英国地球科学部名誉教授杜伦大学。 他于一九七六年获选为英国皇家学会院士,并于一九九二年获颁伍拉斯顿美国地质学会。[319]

- 洛伦斯 · g · 柯林斯(1931年出生) : 美国石油学家,以他对交代主义的广泛研究而闻名。[320]

- 亨利 · 方丹(生于1924年) : 法国罗马天主教传教士、第三纪地质学家 / 古生物学家、古生代珊瑚专家和考古学家。

- 凯瑟琳 · 海赫(1972年出生) : 德克萨斯理工大学的大气科学家和政治学教授,在那里她是气候科学中心的主任。[321]

- 迈克 · 赫尔姆(1960年出生) : 剑桥大学地理系人文地理学教授。 他曾任伦敦国王学院气候与文化教授(2013-2017年) ,著有《为什么我们对气候变化持不同意见》一书的作者。 他谈到自己的基督教信仰时说:"我相信是因为我还没有发现一个更好的解释美,真理和爱,而不是他们出现在一个由一个美丽、真理和爱情化身的上帝创造的世界。"[322]

- 埃里克 · 普雷斯特(1943年出生) : 太阳能磁流体力学的权威,他在其他人中赢得了乔治·埃勒里·海耳奖。 他曾在圣安德鲁斯大学(University of st. Andrews)就基督教和科学发表过讲话,他在那里担任名誉教授,并且是法拉第研究所的成员。 他还对祈祷、冥想和基督教心理学感兴趣。[323]

- 玛格丽特 · 奥尔: 美国气象学家和新奥尔良 WDSU 气象学家。

- 约翰 · 苏佩(1943年出生) : 国立台湾大学地质学教授,地球科学名誉普林斯顿大学。 他写过诸如《科学之光下基督教认识论思想》等文章[324]

- 罗伯特(鲍勃)怀特: 英国地球物理学家和剑桥大学地球科学系地球物理学教授。 他是法拉第科学与宗教研究所的主管。[325]

工程学

[编辑]- 弗雷德 · 布鲁克斯(1931年出生) : 美国计算机设计师、软件工程师和计算机科学家,以管理 IBM 的 system / 360计算机系列和 os / 360软件支持软件包的开发,然后在他的开创性的书籍人月神话中坦率地写下了这个过程。 布鲁克斯获得了许多奖项,包括1985年的国家技术奖和1999年的图灵奖。 布鲁克斯是一位福音派基督徒,他积极参与了校际基督教联谊会,并于1973年担任中卡罗来纳州比利 · 格雷厄姆十字军执行委员会的主席。[326]

- 约翰 · 达比里(1980年出生) : 尼日利亚裔美国生物物理学家,斯坦福大学航空与生物工程学教授,麦克阿瑟研究员,《大众科学》杂志"十大杰出"科学家之一。[327]

- 雷蒙德 · 瓦汉 · 达马迪安(1936年出生) : 医生和发明家创造了 MRI (磁共振扫描机)。 他是一位年轻的创世主义者,关于为什么他没有收到2003年的诺贝尔生理学或医学奖,因为他提出了这个想法,并致力于核磁共振成像的发展。

- Tim Berners-Lee (生于1955年) : 英国工程师和计算机科学家,最著名的是万维网的发明者。 他目前是牛津大学和麻省理工学院计算机科学教授。[328][329] 伯纳斯-李是作为圣公会教徒长大的,后来成为了一位唯一主义的普世主义基督徒。[330] 他说:"像许多人一样,我在青少年时期就拒绝了自己的宗教教育。.. 像许多人一样,当我们有孩子的时候,我又回到了宗教。"。[331] 他和他的妻子想要教他们的孩子灵性,在听到一位一神论的牧师访问了 UU 教堂之后,他们选择了这种方式。[332] 他是那个教会的积极成员,他坚持这个教会,因为他认为这是一种宽容和自由的信仰。[333] 他说:"我相信,与许多宗教相关的生活哲学远比随之而来的教条更加健全。 所以我确实尊重他们。"

- 帕特 · 格尔辛格(1962年出生) : 美国计算机工程师和建筑师,英特尔公司首席技术官,目前是 VMware 的首席执行官。 他是英特尔80486的设计师和设计经理,该公司提供了从20世纪80年代到90年代个人电脑革命所需的处理能力。[334][335]

- 唐纳德 · 克努斯(1938年出生): 美国计算机科学家,数学家,斯坦福大学的名誉教授。 他是多卷作品《计算机编程艺术》和《圣经经文照明》(1991) ,ISBN 0-89579-252-4。[336]

- 迈克尔 · c · 麦克法兰(1948 -) : 美国计算机科学家,伍斯特圣十字学院院长

- Rosalind Picard (出生于1962年) : 麻省理工学院媒体艺术与科学教授、麻省理工学院(MIT Media Lab)情感计算研究小组(Affective Computing Research Group)创始人、"事物思考联盟"(Things That Think Consortium)联席主任、 Affectiva 公司首席科学家兼联合创始人。 皮卡德说,她从小就是一个无神论者,但在成年后皈依了基督教。[337]

- 彼得 · 罗宾逊(计算机科学家)(出生于1952年) : 英国计算机科学家,英国剑桥大学计算机实验室计算机技术教授,他在彩虹小组工作,研究计算机图形学和交互。[338][339]

- 莱昂内尔 · 塔拉森科: 自1997年起担任牛津大学电气工程系主任,最著名的是他在神经网络应用方面的工作。 他领导了夏普洛基库克微波炉的发展,这是第一个将神经网络融入其中的微波炉。[340][341]

- 乔治 · 瓦尔盖塞(1960年出生) : 现任加州大学洛杉矶分校计算机科学系校长教授,微软研究院前首席研究员。[342][343]

- 拉里 · 沃尔(出生于1954年9月27日) : 编程语言 Perl 的创造者。[344]

其他人

[编辑]- 罗伯特 · j · 威克斯(1946年出生) : 临床心理学家,他写过关于精神和心理学的交叉点。 三十多年来,威克斯一直在大学和专业学校教授心理学、医学、护理、神学和社会工作,目前正处于马里兰洛约拉大学阶段。 1996年,他获得了圣十字勋章和教皇勋章,这是教皇为罗马天主教会做出杰出贡献的最高奖章。

- 大卫 · a · 布斯(1938年出生) : 英国应用心理学家,他的研究和教学中心是关于人类、其他物种的成员和社会智能工程系统的行为和反应。 他是伯明翰大学心理学院的荣誉教授。[345]

- 罗伯特 · 埃蒙斯(1958年出生) : 美国心理学家,被认为是世界领先的感恩科学专家。[346] 他是加州大学戴维斯分校的心理学教授,也是《积极心理学》杂志的主编。[347]

- 保罗 · 法默(1959年出生) : 美国人类学家、医生和解放神学的支持者。 他是健康合作伙伴公司(Partners In Health)的联合创始人,哈佛大学(Harvard University)科洛科特隆斯大学(Kolokotrones University)教授、全球健康平等部门(Division of Global Health Equity at london)和马萨诸塞州波士顿妇女医院(Women's Hospital)。[348]

- 大卫 · 迈尔斯(学者)(生于1942年) : 美国心理学家,希望学院的心理学教授。 他是几本书的作者,其中包括名为《心理学,探索心理学,社会心理学和一般读者书籍,书中涉及与基督教信仰和科学心理学有关的问题。[349]

- 阿利斯特 · 麦克格拉斯(生于1953年) : 多产的圣公会神学家,他在《科学神学》中就科学与神学的关系写过文章。 麦克格拉斯拥有牛津大学的两名博士学位,一个是分子生物物理学的哲学博士,另一个是神学神学博士。 他在几本书中回应了新无神论者,也就是说。 道金斯的错觉?. 他是牛津大学的安德烈亚斯 · 伊德雷斯科学和宗教教授。[350]

- 迈克尔 · 赖斯(出生于1960年) : 英国生物伦理学家、科学教育家和英国圣公会牧师。 2006年至2008年,他是英国皇家学会教育主任。 赖斯一直致力于进化论教学,同时也是伦敦大学教育学院的科学教育教授,他是研究与发展专业的主管。[351][352]

- Bienvenido Nebres (1940 -) : 菲律宾数学家,菲律宾马尼拉雅典耀大学总裁,菲律宾国家科学家奖得主

- 贾斯汀 · l · 巴雷特(1971年出生) : 人类发展兴旺中心主任,福勒大学心理学研究生院心理学教授,Barrett 是一位专攻宗教认知科学的认知科学家。 他出版了《认知科学、宗教和神学》(Templeton Press,2011)。 纽约时报》称巴雷特是一位虔诚的基督徒,他相信"一个无所不知的、全能的、完美的上帝带来了宇宙的存在,"他在一封电子邮件中写道。 "我相信人们的目的是爱上帝,爱对方。"'[353]

另见

[编辑]- 基督教与科学

- 天主教堂和科学

- 美国科学联盟

- 基督教数学科学协会

- 科学中的基督徒

- 科学和宗教问题

- 科学技术无神论者名单

- 天主教科学家名单

- 基督教诺贝尔奖获得者名单

- 基督徒名单

- 耶稣会科学家名单

- 犹太科学家和哲学家名单

- 穆斯林科学家名单

- 罗马天主教神职人员科学家名单

- 科学和宗教学者名单

- 科学界的贵格会教徒

- 注册科学家协会

- Veritas 论坛

- 维多利亚学院

注意事项

[编辑]- ^ In 1252 he helped appoint Thomas Aquinas to a Dominican theological chair in Paris to lead the suppression of these dangerous ideas.

- ^ Although Jansenism was a movement within Roman Catholicism, it was generally opposed by the Catholic hierarchy and was eventually condemned as heretical.

- ^ Carl Wilhelm Scheele discovered oxygen earlier but published his findings after Priestley.

- ^ As was Euler. Like Gauss, the Bernoullis would convince both sets of fathers and sons to study mathematics.

- ^ In the biography by Cambell (p. 170) Maxwell's conversion is described: "He referred to it long afterwards as having given him a new perception of the Love of God. One of his strongest convictions thenceforward was that 'Love abideth, though Knowledge vanish away.'"

- ^ He teaches at Kraków, hence the picture of a Basilica from the city.

参考文献

[编辑]- ^ James Clerk Maxwell and the Christian Proposition. MIT IAP Seminar. [13 October 2014].

- ^ Jöckle, Clemens. Encyclopedia of Saints. Konecky & Konecky. 2003: 204.

- ^ A. C. Crombie, Robert Grosseteste and the Origins of Experimental Science 1100–1700, (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1971)

- ^ Lang, Helen S. Aristotle's Physics and Its Medieval Varieties. State University of New York Press. 1992. ISBN 0-7914-1083-8. and Goldstone, Lawrence; Goldstone, Nancy. The Friar and the Cipher. Doubleday. 2005. ISBN 0-7679-1472-4.

- ^ Thomas F. Glick, Steven John Livesey, & Faith Wallis (编). Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. 2005. ISBN 0-415-96930-1.

- ^ Cusa summary. [15 January 2015]. (原始内容存档于21 October 2014).

- ^ Meyers Konversationslexikon 1888–1889, Jahn, I. Geschichte der Biologie. Spektrum 2000, and Mägdefrau, K. Geschichte der Botanik. Fischer 1992

- ^ The Galileo Project. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Danti biography. [15 January 2015].

- ^ The Baconian System of Philosophy. Catholic Encyclopedia.

- ^ Gascoigne, John. The Religious Thought of Francis Bacon. Cusack, Carole M.; Hartney, Christopher (编). Religion and Retributive Logic. Leiden: Brill. 2010: 209–228. ISBN 9789047441151.

- ^ Letter to the Grand Duchess Christina

- ^ Recantation (22 June 1633) as quoted in The Crime of Galileo (1955) by Giorgio de Santillana, p. 312

- ^ Laurentius Paulinus Gothus (1565–1646). [15 January 2015].

- ^ The Galileo Project and Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ^ Cosmovisions and The Galileo Project Rice University's Galileo Project

- ^ Pascal summary. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Archived copy. [2006-03-07]. (原始内容存档于2006-03-07).

- ^ https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=en&lr=&safe=active&q=cache:6JVRTVzuffMJ:collection.nlc-bnc.ca/100/201/300/palaeontologia/03-03-14/2002_1/books/map.htm+%22Nicholas+Steno%22

- ^ Barrow summary. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Caramuel summary. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Galileo Project and University of Hanover's philosophy seminar链接=链接=

- ^ Robert Boyle. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Robert Boyle. [15 January 2015].

- ^ The John Ray Initiative. [15 January 2015].

- ^ John Ray. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Leibniz biography. [15 January 2015].

- ^ The Galileo Project and 1902 Encyclopedia

- ^ Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition

- ^ Whitaker, Harry; Smith, C.U.M.; Finger, Stanley. Brain, Mind and Medicine:: Essays in Eighteenth-Century Neuroscience. Springer Science & Business Media. 27 October 2007: 204–. ISBN 978-0-387-70967-3.

- ^ swedenborg.com

- ^ Letters from Baron Haller to His Daughter on the Truths of the Christian .... [15 January 2015].

- ^ Mathematics and the Divine. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Grimaux, Edouard. Lavoisier 1743–1794. (Paris, 1888; 2nd ed., 1896; 3rd ed., 1899), page 53.

- ^ BOERHAAVES ORATIONS. [15 January 2015].

- ^ This Month in Physics History: November 27, 1783: John Michell anticipates black holes. APS Physics.

- ^ Weighing the World by Russell McCormmach. Google Books.

- ^ Maria Gaetana Agnesi. Encyclopædia Britannica. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Gli scienziati cattolici che hanno fatto lItalia. ZENIT – Il mondo visto da Roma. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Royal Society and Thoemmes

- ^ Lucasian Chair

- ^ Moore, D.T. Kirby, William (1759–1850). Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. 2004. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/15647.

- ^ Armstrong, Patrick. The English Parson-naturalist: A Companionship Between Science and Religion. Gracewing. 2000: 99–102. ISBN 978-0-85244-516-7.

- ^ Pardshaw – Quaker Meeting House. [18 January 2015].

- ^ Catholic Encyclopedia. [29 December 2007].

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh (编). Gregory, Olinthus Gilbert. Encyclopædia Britannica 12 (第11版). London: Cambridge University Press: 577. 1911.

- ^ Essays : Abercrombie, John, 1780–1844 : Free Download & Streaming : Internet Archive. Internet Archive. [15 January 2015].

- ^ http://www.oum.ox.ac.uk/geocolls/buckland/bio3.htm

- ^ Emling, Shelley. The Fossil Hunter: Dinosaurs, Evolution, and the Woman whose Discoveries Changed the World. Palgrove Macmillan. 2009: 143. ISBN 978-0-230-61156-6.

- ^ Memoirs of Marshall Hall, by his widow

- ^ Hall, Charlotte; Hall, Marshall (1861). Memoirs of Marshall Hall, by his widow. London : R. Bentley. p. 322

- ^ Christianity and the Emerging Nation States. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh (编). Hitchcock, Edward. Encyclopædia Britannica 13 (第11版). London: Cambridge University Press: 533. 1911.

- ^ Buckingham Mouheb, Roberta (2012). Yale Under God, p. 110. Xulon Press, ISBN 9781619968844

- ^ 约翰·J·奥康纳; 埃德蒙·F·罗伯逊, Riemann, MacTutor数学史档案 (英语) Accessed July 29, 2013.

- ^ William Whewell. [15 January 2015].

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20030808112309/http://mubs.mdx.ac.uk/research/Discussion_Papers/Mathematics_and_Statistics/maths_dpaper_no_5.pdf链接=链接=

- ^ BBC – History – Michael Faraday. [15 January 2015].

- ^ The religion of Michael Faraday, physicist. [15 January 2015].

- ^ http://www.victorianweb.org/science/science_texts/bridgewater/babbage_intro.htm

- ^ Charles Babbage. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Clifford A. Pickover (2009). "The Math Book: From Pythagoras to the 57th Dimension, 250 Milestones in the History of Mathematics". Sterling Publishing Company, Inc. p. 218

- ^ Scientists of Faith and University of California, Santa Barbara

- ^ The College of Charleston and Newberry College

- ^ The ten gentlemen who founded the British Meteorological Society on 3 April 1850 in the library of Hartwell House, near Aylesb (PDF). [15 January 2015]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于4 August 2012).

- ^ 1879MNRAS..39..235. Page 235. [15 January 2015].

- ^ James Clerk Maxwell and religion, American Journal of Physics, 54 (4), April 1986, p.314

- ^ James Clerk Maxwell and religion, American Journal of Physics, 54 (4), April 1986, p. 312–317 ; James Clerk Maxwell and the Christian Proposition by Ian Hutchinson

- ^ Outlines of natural theology for the use of the Canadian student [microform] : selected and arranged from the most authentic sources : Bovell, James, 1817–1880 : Free Download & Streaming : Internet Archive. Internet Archive. [15 January 2015].

- ^ CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Mendel, Mendelism. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Edward Edelson (2001), "Gregor Mendel: And the Roots of Genetics". Oxford University Press. p. 68

- ^ No. 1864: Philip and Edmund Gosse. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Gutenberg text of Darwiniana and ASA

- ^ Dictionary of Australian Biography We-Wy. [15 January 2015].

- ^ "Science and the Bible" at Google Books and Engines of Our Ingenuity

- ^ The religion of James Prescott Joule

- ^ Sheets-Pyenson, Susan (1996), "John William Dawson: Faith, Hope and Science", McGill-Queen's Press MQUP. pp. 124–126

- ^ The Vicentians链接=链接=

- ^ Ann Lamont. Joseph Lister: father of modern surgery. Creation. March 1992, 14 (2): 48–51.

Lister married Syme's daughter Agnes and became a member of the Episcopal church

|author=和|last=只需其一 (帮助) - ^ Baruch A. Shalev, 100 Years of Nobel Prizes (2003), Atlantic Publishers & Distributors , p.57: between 1901 and 2000 reveals that 654 Laureates belong to 28 different religion Most (65.4%) have identified Christianity in its various forms as their religious preference.

- ^ Shalev, Baruch (2005). 100 Years of Nobel Prizes. p. 59

- ^ GLADSTONE, John Hall: 472.

- ^ Ward, Thomas Humphry. Men of the Time: A Dictionary of Contemporaries, Containing Biographical Notices of Eminent Characters of Both Sexes. G. Routledge and Sons. 1887: 431.

- ^ George Gabriel Stokes. The Gifford Lectures. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Search results. The Gifford Lectures. [15 January 2015].

- ^ University of Durham

- ^ Yale Finding Aid Database : Guide to the Enoch Fitch Burr Papers. [15 January 2015].

- ^ The Extraterrestrial Life Debate, 1750–1900. [15 January 2015].

- ^ physicsworld.com. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Haas, Jr, J. W. The Reverend Dr. William Henry Dallinger, F.R.S. (1839–1909). Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. January 2000, 54 (1): 53–65. JSTOR 532058. PMID 11624308. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2000.0096.

- ^ Bonjour, Edgar. Theodor Kocher. Berner Heimatbücher 40/41 2nd (2., stark erweiterte Auflage 1981). Bern: Verlag Paul Haupt. 1981 [1st. pub. in 1950 (http://d-nb.info/363374914)]. ISBN 3258030294 (德语).

- ^ Peter J. Bowler, Reconciling Science and Religion: The Debate in Early-Twentieth-Century Britain (2014). University of Chicago Press. p. 35. ISBN 9780226068596. "Both Lord Rayleigh and J. J. Thomson were Anglicans."

- ^ Seeger, Raymond. 1986. "J. J. Thomson, Anglican," in Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith, 38 (June 1986): 131–132. The Journal of the American Scientific Affiliation. ""As a Professor, J.J. Thomson did attend the Sunday evening college chapel service, and as Master, the morning service. He was a regular communicant in the Anglican Church. In addition, he showed an active interest in the Trinity Mission at Camberwell. With respect to his private devotional life, J.J. Thomson would invariably practice kneeling for daily prayer, and read his Bible before retiring each night. He truly was a practicing Christian!" (Raymond Seeger 1986, 132)."

- ^ Richardson, Owen. 1970. "Joseph J. Thomson," in The Dictionary of National Biography, 1931–1940. L. G. Wickham Legg – editor. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Otto Glasser " Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen and the Early History of the Roentgen Rays" Norman Publishing, 1993,p.135 [1]

- ^ Duhem summary. [15 January 2015].

- ^ http://pirate.shu.edu/~jakistan/JakisBooks/PierreDuhem.htm

- ^ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

- ^ Niall, R.; Martin, D. Pierre Duhem: Philosophy and History in the Work of a Believing Physicist. Open Court Publishing. January 1991. ISBN 978-0-8126-9160-3.

- ^ Hilbert, Martin. Pierre Duhem and Neo-Thomist Interpretations of Physical Science [microform]. Thesis (Ph.D.)--University of Toronto. 2000. ISBN 978-0-612-53764-4.

- ^ CTS History. [2007-04-13]. (原始内容存档于2007-04-06).

- ^

Obituary: James Britten

Obituary: James Britten

- ^ http://www.stephenjaygould.org/ctrl/gould_darwin-on-trial.html

- ^ Wissemann, Volker (2012). Johannes Reinke: Leben und Werk eines lutherischen Botanikers. Volume 26 of Religion, Theologie und Naturwissenschaft / Religion, Theology, and Natural Science. Vandenhoeck & Ruprech. ISBN 3525570201

- ^ M.C. Marconi, Mio Marito Guglielmo, Rizzoli 1995, p. 244.

- ^ In S. Popov, "Why I Believe in God", Bulgarian Ministry of Education, Science, and Culture, letter No. 92-00-910/ 12 December 1992

- ^ I believe in God and in evolution. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Villanova University's Mendel Medal page on Dr. Francis P. Garvan 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2015-09-12.

- ^ Catholic Action ...: A National Monthly. 1922: 28, 34.

- ^ Second paragraph of Page 26 in a paper from Middlesex UniversityMiddlesex University article链接=链接=

- ^ Gilley, Sheridan; Stanley, Brian (2006). The Cambridge History of Christianity: Volume 8, World Christianities C.1815-c.1914. Cambridge University Press. p. 180. ISBN 9780521814560

- ^ Man of science-and of God from The New American (January 2004) via TheFreeLibrary.com

- ^ Astrophysics and Mysticism: the life of Arthur Stanley Eddington\protect\footnote{Originally presented as talk at the ``Faith of Great Scientists Seminar, MIT, January 2003}. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Alexis Carrel. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Charles Glover Barkla. [15 January 2015].

- ^ School of Mathematics and Statistics. "Charles Glover Barkla" (2007), University of St Andrews, Scotland. JOC/EFR.

- ^ H.S. Allen (1947), Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society, Vol. 5, No. 15,. "Charles Glover Bark"

- ^ Charles Glover Barkla, Complete Dictionary of Scientific Biography (2008)

- ^ IEEE. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Fleming, Sir John Ambrose. 'The evidence of things not seen'.. Christian Evidence Committee of the Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge. 1904.

- ^ Numbers, Ronald L. The Creationists. University of California Press. 1993: 143–144. ISBN 978-0-520-08393-6.

- ^ Philipp Lenard. [15 January 2015].

- ^ The who's who of Nobel Prize winners, 1901–1995, p. 178

- ^ Robert A. Millikan – Biographical. [15 January 2015].

- ^ "Millikan, Robert Andrew", Who's Who in America v. 15, 1928–1929, p. 1486

- ^ The Religious Affiliation of Physicist Robert Andrews Millikan. adherents.com

- ^ "Medicine: Science Serves God," Time, June 4, 1923. Accessed 19 January 2013.

- ^ Evolution in Science and Religion (1927), 1973 edition: Kennikat Press, ISBN 0-8046-1702-3

- ^ "Karl Landsteiner", Jewish Virtual Library

- ^ Anna L. Staudacher: "… meldet den Austritt aus dem mosaischen Glauben". 18000 Austritte aus dem Judentum in Wien, 1868–1914: Namen – Quellen – Daten. Peter Lang, Frankfurt, 2009, ISBN 978-3-631-55832-4, p. 349

- ^ American Institute of Chemical Engineers and Worldcat

- ^ in F.E. Trinklein, "The God of Science", Exposition Press 1983, pag. 64

- ^ M. Born, Physics in my generation, Pergamon Press 1956

- ^ M. Born in L. Laudan, Beyond Positivism and Relativism: Theory, Method, and Evidence, Westview Press 1996

- ^ Whittaker summary. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Physics and Society newsletter April 2003 Commentary. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Science: Cosmic Clearance. 13 January 1936 [15 January 2015].

- ^ Victor F. Hess, Physicist, Dies; Shared the Nobel Prize in 1936; Was Early Experimenter on Conductivity of Air - Taught at Fordham Till 1958. 19 December 1964 [2018-08-06].

- ^ My Faith. November 3, 1946 [2018-08-06].

- ^ Gould on God Can religion and science be happily reconciled?

- ^ Super User. Catholic Education Resource Center. Catholic Education Resource Center. [15 January 2015].

|author=和|last=只需其一 (帮助) - ^ Royal Society of Chemistry HISTORICAL GROUP biography page

- ^ The Christian Science Journal

- ^ Western Kentucky UniversityASA's book reviews section

- ^ Anderson, Ted. The Life of David Lack: Father of Evolutionary Ecology. OUP USA. 18 July 2013: 121–131. ISBN 978-0-19-992264-2.

- ^ Villanova University's Mendel Medal page on Hugh Stott Taylor

- ^ From Alexander Leitch, A Princeton Companion, copyright Princeton University Press (1978).

- ^ Coulson summary. [15 January 2015].

- ^ De Waal, Frans. Book Review – The Price of Altruism – By Oren Harman. The New York Times. 2010-07-09.

- ^ Dobzhansky, Theodosius, Nothing in Biology Makes Sense Except in the Light of Evolution, American Biology Teacher, March 1973, 35 (3): 125–129, JSTOR 4444260

|work=和|journal=只需其一 (帮助);|JSTOR=和|jstor=只需其一 (帮助) - ^ https://www.newscientist.com/channel/life/evolution/mg14920155.100

- ^ (Margenau 1985, Vol. 1).Margenau, Henry. 1985. "Why I Am a Christian", in Truth (An International, Inter-disciplinary Journal of Christian Thought), Vol. 1. Truth Inc., in cooperation with the Institute for Research in Christianity and Contemporary Thought, the International Christian Graduate University, Dallas Baptist University and the International Institute for Mankind. USA.

- ^ AFTER BROTHERHOOD'S GOLDEN AGE. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Biography of Wernher Von Braun. [15 January 2015].

- ^ The religion of Wernher von Braun, rocket engineer, inventor. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Pascual Jordan, Glory and Demise and his legacy in contemporary local quantum physics, p. 5链接=链接=

- ^ Forschungsstelle Universitätsgeschichte der Universität Rostock. Jordan, Pascual @ Catalogus Professorum Rostochiensium. [15 January 2015].

|author=和|last=只需其一 (帮助) - ^ Moon, Irwin A.; Everest, F. Alton & Houghton, Will H. Early Links Between the Moody Bible Institute and the American Scientific Affiliation. Perspectives on Science and Christian Faith. December 1991, 43: 249–258 [2007-02-09].

- ^ Hartzler, H. Harold. Foreword. Science Speaks. by Peter W. Stoner, revised and HTML formatted by Don W. Stoner. November 2005 [2007-02-09].

- ^ Archived copy. [2013-01-15]. (原始内容存档于2012-11-10).

- ^ https://www.jewishvirtuallibrary.org/jsource/biography/cori.html

- ^ Biographical Memoirs Home. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Mormon Scientist: The Life and Faith of Henry Eyring by Henry J. Eyring

- ^ Steel, Martha Vickers, Women in computing: experiences and contributions within the emerging computing industry (PDF) (CSIS 550 History of Computing – Research Paper), 11 December 2011 [1 August 2014], (原始内容 (PDF)存档于23 November 2011)

|accessdate=和|access-date=只需其一 (帮助) - ^ Pam Bonee, William G. Pollard, Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture.

- ^ Eliel, Ernest L., Frederick Dominic Rossini, Biographical Memoirs, National Academy of Sciences.

- ^ The Palm Beach Post – Google News Archive Search. [15 January 2015].

- ^ University of Maryland and ASA

- ^ Pace, Eric. Dr. Jerome Lejeune Dies at 67 - Found Cause of Down Syndrome - NYTimes.com. The New York Times. 12 April 1994 [15 January 2015].

- ^ NCRegister – Remembering Jerome Lejeune. National Catholic Register. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Introduction Alonzo Church: Life and Work (PDF). [6 June 2012]. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于1 September 2012).

A deeply religious person, he was a lifelong member of the Presbyterian church.

- ^ Walton Lectures. [15 January 2015].

- ^ The religion of Nevill Mott, Nobel Prize winner; photographic emulsion. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Obituary of Nevill Francis Mott in the Washington Post

- ^ Fasenmyer biography. [15 January 2015].

- ^ The religion of John Eccles, Nobel Prize-winner in Medicine and Physiology. [15 January 2015].

- ^ The religion of Arthur Schawlow, Nobel Prize-winning physicist; worked with lasers. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Margenau, H., Cosmos, Bios, Theos: Scientists Reflect on Science, God, and the Origins of the Universe, Life, and Homo Sapiens, Open Court Publishing Company: 105, 1992

|author-link=和|authorlink=只需其一 (帮助) co-edited with Roy Abraham Varghese. This book is mentioned in a December 28, 1992 Time magazine article: Galileo And Other Faithful Scientists - ^ Brazilian Academy of Sciences 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2007-06-27.

- ^ Obituary 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2006-05-11. and CiS

- ^ janfeb09email. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Cuadrado, José Angel García. Mariano Artigas (1938–2006). In memoriam.. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Science: Man and Strontium 90. February 18, 1957 [May 5, 2010].

- ^ Chapter 13: The Practice of Secrecy

- ^ Regulation Magazine Vol. 13 No. 1

- ^ Numbers, Ronald. The Creationists: From Scientific Creationism to Intelligent Design, Expanded Edition. Harvard University Press. November 30, 2006. ISBN 0-674-02339-0.

- ^ 22 Peacocke. [15 January 2015].

- ^ John Billings, founder of natural family planning method, dies at 89 – website The Catholic News

- ^ Awards, Biology, Wheaton College, Illinois

- ^ Science in Christian Perspective. [15 January 2015].

- ^ http://pirate.shu.edu/~jakistan/JakisBooks/SaviorOfScience.htm

- ^ A Scientist Reflects on Religious Belief. [15 January 2015].

- ^ The color-magnitude diagram for the globular cluster M 3.. Bibcode:1953AJ.....58...61S. doi:10.1086/106822. 使用

|accessdate=需要含有|url=(帮助) - ^ The Bruce Medalists: Allan Sandage. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Science and the Spiritual Quest. [15 January 2015].

- ^ John Templeton Foundation: Participants. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Ernan McMullin dies – NCSE. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Catholic transplant pioneer, Nobel Prize-winner Joseph Murray dies. The Catholic Review. [15 January 2015].

- ^ http://www.templetonprize.org/bios_recent.html[永久失效链接]

- ^ Nobel Prize winner Charles Townes on evolution and "intelligent design". [15 January 2015].

- ^ http://www.templetonprize.org/townes_pressrelease.html

- ^ Thirring, Walter. Cosmic Impressions: Traces of God in the Laws of Nature. Templeton Press. May 31, 2007. ISBN 978-1-59947-115-0.

- ^ I would like to add a remark on my religious believes. Brought up rather conservative catholique on. [2016].

- ^ InterVarsity Press. R. J. Berry. [15 January 2015].

|author=和|last=只需其一 (帮助) - ^ http://www.cis.org.uk/about/past_presidents.shtml

- ^ "Ferid Murad autobiography". Nobel Foundation

- ^ Faraday Institute Biography 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2007-07-03.

- ^ The 50 Smartest People of Faith. The Best Schools. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Untitled Document. [15 January 2015].

- ^ http://www.experiencefestival.com/robert_t_bakker

- ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qdT9_7WhhyQ

- ^ "I believe in God. I pray every single night of my life, but I have a very complicated sense of religion, and I am pretty fuzzy in that segment of my life" in http://www.irishtimes.com/life-and-style/people/meet-ireland-s-new-nobel-laureate-william-c-campbell-1.2385532

- ^ Commentary on the Life of Ben Carson (PDF). Johns Hopkins University.

- ^ Faith and the Human Genome (PDF). [15 January 2015].

- ^ Former NHGRI Director Francis S. Collins. [15 January 2015].

- ^ https://onbeing.org/programs/carl-feit-anne-foerst-and-lindon-eaves-science-and-being/

- ^ http://serendip.brynmawr.edu/sci_cult/lesswrong/descartes/eaves.html

- ^ Darrel Falk – The BioLogos Forum. BioLogos.org. [15 January 2015]. (原始内容存档于1 May 2012).

- ^ Biography. [15 January 2015].

- ^ The Selfless Gene. [15 January 2015].

- ^ EWTN.com – Nobel Prize Winner Participates at Vatican Conference. EWTN. [15 January 2015].

- ^ https://www.faraday.st-edmunds.cam.ac.uk/Biography.php?ID=13

- ^ Founding Members of ISSR. [15 January 2015]. (原始内容存档于29 March 2008).

- ^ Main. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Boston Globe

- ^ https://www.cis.org.uk/about-cis/presidents/

- ^ https://biologos.org/blogs/archive/serving-god-in-the-struggle-against-cancer-an-interview-with-larry-kwak

- ^ Denis O. Lamoureux Webpage. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Gaudette, Karen. The mother of cheesemaking has art down to a science. The Seattle Times. May 16, 2007 [2009-01-18].

- ^ State: Intelligent design makes for big bang. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Archived copy. [2010-02-20]. (原始内容存档于2008-04-09).

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20061012120932/http://www.stmarylebow.co.uk/?download=BoyleLecture05.pdf

- ^ Evolving Truth. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Neuroscience: Solving the brain. Nature News & Comment. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Of two minds. [15 January 2015].

- ^ About Us : Who We Are : Board of Advisors 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2007-01-23.

- ^ Barlow, Rich. Mathematics and faith explain altruism. The Boston Globe. 27 September 2008.

- ^ http://www.ncregister.com/daily-news/concussion-doctors-catholic-faith-guided-his-investigation-of-nfl-stars-dea

- ^ CiS Presidents list

- ^ Archived copy. [September 19, 2006]. (原始内容存档于October 8, 2007).

- ^ Dinosaur Shocker. Smithsonian. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Schweitzer's Dangerous Discovery. Discover Magazine. [15 January 2015].

- ^ https://scienceandbelief.org/2011/01/27/death-as-preservative/

- ^ http://www.nndb.com/people/868/000100568/

- ^ http://stonehillprinceton.org/staff/andy-bocarsly

- ^ Archived copy. [2008-06-05]. (原始内容存档于2007-11-30).

- ^ Little Falls native wins Nobel Prize in chemistry. TheCatholicSpirit.com. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Villanova University

- ^ https://www.calvin.edu/publications/spark/2006/summer/martinez-todd.htm

- ^ Henry F. Schaefer, III链接=链接=

- ^ Strobel, Lee, The Case For Faith: 111, 2000, ISBN 0-310-23469-7

|ISBN=和|isbn=只需其一 (帮助) - ^ http://www.veritas.org/nyt-columnist-interviews-theoretical-chemist-on-faith-and-science/

- ^ http://www.australasianscience.com.au/article/issue-march-2012/immersed-chemistry.html

- ^ University of Delaware,University of Notre Dame Press, and Interview at Ignatius Insight

- ^ Overbye, Dennis. Math Professor Wins a Coveted Religion Award. The New York Times. 16 March 2006.

- ^ http://www.templetonprize.org/barrow_bios.html

- ^ http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2002ASSL..279.....B

- ^ http://www.uzh.ch/about/portrait/awards/hc/2011/theol.html

- ^ http://www.sewanee.edu/newstoday/top/commence-2017-two.php

- ^ https://oxfordconversations.org/katherine-blundell-scholars

- ^ https://www.faraday.st-edmunds.cam.ac.uk/Biography.php?ID=33

- ^ http://www.amcf-int.org/resources/other/god.htm

- ^ https://www.faraday.st-edmunds.cam.ac.uk/CIS/briggs/Andrew%20Briggs%20-%20lecture.htm

- ^ http://www.counterbalance.org/ctns-vo/chiao-body.html

- ^ https://melwild.wordpress.com/2017/07/11/the-spiritual-realm/

- ^ Baylor Lariat

- ^ Universe and Multiverse, Part 1. BioLogos.org. [15 January 2015].

- ^ http://globalstories.tudelft.nl/story/cees-dekker/

- ^ https://www.calvin.edu/publications/spark/2006/fall/gabrielse-gerald.htm

- ^ https://www.faraday.st-edmunds.cam.ac.uk/CIS/Gabrielse/discussion.htm

- ^ ASA list of science blogs

- ^ What to do with those pesky religious skeptics by Greg Laden on scienceblogs.com

- ^ http://biologos.org/blog/karl-giberson-moves-on-to-create-more-time-for-writing

- ^ http://www.space.com/colleges/college_gingerich_profile_000921.html

- ^ http://www.st-edmunds.cam.ac.uk/cis/gingerich/index.html

- ^ J. Richard Gott on Life, the Universe, and Everything. [15 January 2015]. (原始内容存档于28 September 2007).

- ^ Not Scientific Quality I was quite disappointed in the article on. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Where Is the Best Clock in the Universe?. arXiv blog. MIT, Technology Review. [2011-11-18].

The widespread belief that pulsars are the best clocks in the universe is wrong, say physicists.

- ^ Hartnett, John; Andre, Luiten,. Colloquium: Comparison of Astrophysical and Terrestrial Frequency Standards. Reviews of Modern Physics (Cornell University Library, Reviews of Modern Physics, vol. 83, 2011). 2011, 83: 1–9. Bibcode:2011RvMP...83....1H. arXiv:1004.0115

. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.83.1.

. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.83.1. We have re-analyzed the stability of pulse arrival times from pulsars and white dwarfs using several analysis tools for measuring the noise characteristics of sampled time and frequency data. We show that the best terrestrial artificial clocks substantially exceed the performance of astronomical sources as time-keepers in terms of accuracy (as defined by cesium primary frequency standards) and stability. ...we show that detailed accuracy evaluations of modern terrestrial clocks imply that these new clocks are likely to have a stability better than any astronomical source up to comparison times of at least hundreds of years.

- ^ Starlight, Time and the New Physics tour with Dr John Hartnett. creation.com. 2012 [23 February 2012]. (原始内容存档于26 April 2009).

- ^ https://smart.mit.edu/news-events/news/five-from-smart-elected-to-the-national-academy-of-engineering

- ^ http://www.veritas.org/danielhastings-career/

- ^ Templeton Foundation, Journal of Mathematical Physics, and ISSR 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2005-03-07.

- ^ The religion of Antony Hewish, Nobel Prize-winning physicist; radio astronomer; known for work on pulsars. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Polkinghorne, J. C.; Polkinghorne, John; Beale, Nicholas. Questions of Truth: Fifty-One Responses to Questions about God, Science, and Belief. Westminster John Knox Press. 16 January 2009: 12 [27 July 2012]. ISBN 978-0-664-23351-8.

- ^ http://2012daily.com/?q=node/121

- ^ Cambridge University. April 17, 2011. Retrieved 2011-04-23. "The new study is based on earlier research which Professor Humphreys carried out with the Oxford astrophysicist, Graeme Waddington, in 1983. This identified the date of Jesus’ crucifixion as the morning of Friday, April 3rd, AD 33 – which has since been widely accepted by other scholars as well. For Professor Humphreys, who only studies the Bible when not pursuing his day-job as a materials scientist, this presented an opportunity to deal with the equally difficult issue of when (and how) Jesus’ Last Supper really took place."

- ^ Stephen Hawking, the Big Bang, and God. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Christopher Isham

- ^ https://shop.reasons.org/product/347/how-old-is-the-universe

- ^ http://www.godandscience.org/youngearth/age_of_universe_evidence.html

- ^ http://biologos.org/uploads/projects/louis_white_paper.pdf链接=链接=

- ^ https://www.americamagazine.org/politics-society/2016/11/16/did-you-know-theres-society-catholic-scientists

- ^ A medida que voy aprendiendo, trato de compatibilizar la ciencia con la religión. Clarin.com. [15 January 2015].

- ^ http://whyibelieve.org.au/mckenzie.html

- ^ https://web.archive.org/web/20150329120640/http://greenbelt.org.uk/contributors/tom-mcleish/

- ^ http://www2.physics.umd.edu/~misner/Brief%20CV.pdf链接=链接=

- ^ http://csca.ca/events/event/barth-netterfield-looking-back-to-the-beginning-an-astrophysicist-discusses-microwaves-balloons-and-god/

- ^ Interview of Don Page at the American Institute of Physics page

- ^ Susskind, Leonard. The Black Hole War: My battle with Stephen Hawking to make the world safe for quantum mechanics. Little, Brown. 2008: 253. ISBN 0-316-01640-3.

- ^ Holder, Rodney. Big Bang Big God: A Universe Designed for Life?. Lion Books. 18 October 2013: 128–129. ISBN 978-0-7459-5626-8.

- ^ Founding Members of ISSR. [15 January 2015]. (原始内容存档于7 March 2005).

- ^ Öberg, Karin I. (2009). Complex processes in simple ices – Laboratory and observational studies of gas-grain interactions during star formation (Ph.D.). Leiden University.[2]

- ^ Öberg, Karin. Home. The Öberg Astrochemistry Group. Harvard University.

- ^ Andrew Pinsent – Home. [15 January 2015].

- ^ DELPHI Notes. [15 January 2015].

- ^ His own website

- ^ http://baylorlariat.com/2011/10/18/baylor-welcomes-renowned-researcher/

- ^ Russell Stannard, Science & Wonders, p74

- ^ http://researcherslinks.com/current-issues/Andrew-Steane-Faithful-to-Science-The-Role-of-Science-in-Religion-Oxford-University-Press-2014-255pp-1999-ISBN9780198716044/9/7/146/html

- ^ Rutherford Medal. Royal Society of New Zealand. [5 November 2014].

- ^ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uChUUowga8k

- ^ Tipler, Frank J. THE OMEGA POINT AS ESCHATON: ANSWERS TO PANNENBERGS QUESTIONS FOR SCIENTISTS. Zygon: 217–253. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9744.1989.tb01112.x.

- ^ Deutsch, David. The Ends of the Universe. The Fabric of Reality: The Science of Parallel Universes—and Its Implications. London: Penguin Press. 1997. ISBN 0-7139-9061-9.

- ^ https://www4.hku.hk/hongrads/index.php/archive/graduate_detail/274

- ^ Archived copy. [2010-06-18]. (原始内容存档于2010-06-16).

- ^ EMFCSC – Professor Antonino Zichichi's Short Biography. [15 January 2015].

- ^ International Seminar on Nuclear War and Planetary Emergencies. [15 January 2015].

- ^ http://www.testoffaith.com/resources/resource.aspx?id=224

- ^ Articles in opposition to creationism

- ^ Banerjee, Neela. Spreading the global warming gospel. Los Angeles Times. December 7, 2011 [September 8, 2013].

|author=和|last=只需其一 (帮助) - ^ I’m a believer. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Faraday Institute 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2006-12-30. and Eric Priest's website

- ^ Thoughts on the Epistemology of Christianity in Light of Science. [15 January 2015].

- ^ http://www.rejesus.co.uk/site/module/faith_v_science/P9/index.html

- ^ Faculty Biography at UNC.

- ^ Archived copy. [2012-07-24]. (原始内容存档于2012-03-08).

- ^ Sir Tim Berners-Lee joins Oxford's Department of Computer Science. University of Oxford.已忽略未知参数

|Agency=(建议使用|agency=) (帮助) - ^ Tim Berners-Lee | MIT CSAIL (英语).

- ^ Faces of the week. (原始内容存档于26 September 2003).

- ^ Berners-Lee, Tim. 1998. The World Wide Web and the "Web of Life".

- ^ Stephanie Sammartino McPherson. 2009. Tim Berners-Lee: Inventor of the World Wide Web. Twenty-First Century Books, p. 83: "A Church Like The Web".

- ^ Eden, Richard. 22 May 2011. "Internet pioneer Sir Tim Berners-Lee casts a web of intrigue with his love life", The Telegraph.

- ^ https://blog.smartbear.com/software-quality/gelsinger-and-meyer-two-cpu-designers-who-changed-the-world/

- ^ https://findinggodinsiliconvalley.com/pat-gelsinger-ceo-of-vmware-balancing-faith-family-and-work/

- ^ 252

- ^ Petricevic, Mirko (2007-11-03). "A scientist who embraces God". The Record (Kitchener, Ontario: Metroland Media Group Ltd.). Retrieved 2008-05-06.

- ^ https://speedflix.com/episodes/89036/machines-in-the-image-of-god

- ^ https://www.cai.cam.ac.uk/people/peter-robinson

- ^ Lionel Tarassenko链接=链接=

- ^ http://www.veritas.org/science-are-we-machines/

- ^ http://cseweb.ucsd.edu/~varghese/whyIbelieve.pdf链接=链接=

- ^ http://web.cs.ucla.edu/~varghese/

- ^ http://blogs.discovermagazine.com/gnxp/2008/07/larry-wall-fundamentalist-non-creationist-programmer/

- ^ http://christianacademicnetwork.net/newjoomla/index.php/contributions/biblical-creationism

- ^ http://www.mentorcoach.com/positive-psychology-coaching/interviews/interview-robert-emmons-2/

- ^ http://www.first30days.com/experts/dr-robert-emmons

- ^ https://www.pih.org/article/dr.-paul-farmer-how-liberation-theology-can-inform-public-health

- ^ https://www.cardus.ca/comment/article/redeeming-psychology-means-taking-psychological-science-seriously/

- ^ New Andreas Idreos Professor of Science and Religion. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Today: Tuesday 28 July 2009. BBC News. 2009-07-28.

- ^ Michael Reiss – UCL Institute of Education, University College London. [15 January 2015].

- ^ Darwin's God. The New York Times. 2007-03-04.

外部链接

[编辑]- 剑桥基督教科学组织(CiS)

- 基督徒在科学网站

- 伊恩 · 拉姆齐中心,牛津

- 注册科学家协会——主要是英国教会

- 《基督教观点的科学》(ASA)

- 加拿大科学及基督教联合会

- 国际科学与宗教学会的创始成员。(包括基督教在内的各种信仰)

- 基督教数学科学协会

- 世俗人文主义网站关于科学和宗教的文章

- 由 Google Scholar 编制索引的 Ikponmwosa 出版物

[[Category:科学家列表]]