土耳其太陽能發電

土耳其的氣候多以晴朗為主,當地的太陽能使用潛力極大,尤其是東南安那托利亞地區與地中海地區明顯。[3]太陽能在該國的可再生能源比重持續上升,目前十千兆瓦(GW)太陽能光電模組的發電量[4]已經佔了全國總發電量的5%。[5]此外太陽熱能在土耳其也非常重要。[6](p. 29)

雖然土耳其與西班牙的天氣幾乎是一樣的,但土耳其在2021年的太陽能發電設備卻遠少於西班牙。[7](p. 49)不過太陽能發電也補貼了煤炭與化石天然氣發電,[8](p. 9)因為每安裝一千GW太陽能發電設備就可節省一億多美元的天然氣進口成本,[9]多餘的電力還可以出口國外。[10]

大多數全新的太陽能發電都是作為混合發電廠的一部分進行招標。[11][12]在現有運行中依賴進口的煤電廠在沒有獲得補貼的情況下,建設新的太陽能發電廠往往會更便宜於前者。[13]然而,英國智庫Ember也列出了建設公用事業規模的太陽發電廠的幾個障礙,包括太陽能發電變壓器的新電網容量不足,[14]任何單個太陽能發電廠的裝機容量上限為50MW,以及該國不允許大型消費者為新的太陽能裝置簽署長期購電協議。[13]Ember表示,屋頂用太陽能發電的技術潛力為120GW,幾乎為2023年總產能的十倍,他們認為這已經足以提供該國2022年總需求的45%。[15]

背景

[編輯]

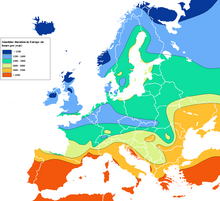

土耳其氣候多以晴朗為主,是太陽能發電的理想之地。其每年的日照時間約為2600小時(每天約七小時),[16][17]幾乎是德國的兩倍,然而德國的太陽能發電能力卻是土耳其的五倍。[18]土耳其的年均太陽輻照度超過一百萬太瓦·時,[1]即約1500 kW·h/(m2·yr)或者超過4 kW·h/(m2·d),[16][1]這意味着土耳其只需用太陽能電池板覆蓋不到5%的國土面積,就能提供其所需的全部能源。[19]此外,太陽能也可能優於風力發電與水力發電等其他可再生能源,這是因為該國夏季風速與降雨量可能較低,而夏季正好也是空調需求的高峰期。[20]

自1970年代以來,太陽能熱水器已在土耳其相當普遍,[1]然而第一批的太陽能發電許可證事實上直到2014年才發放。[18]國際能源署執行董事法提赫·比羅爾表示土耳其的太陽能利用率在2021年仍然不到3%。[21]

政策與法規

[編輯]目前土耳其計劃在2035年將太陽能發電能力增加到將近53GW。[22]發電量超過五MW的系統如要向電網供電就必須獲得能源市場監管局的許可。[18]

自2021年起,新設備的上網電價以土耳其里拉為單位(但最高約為每kWh0.05美元[17]),並由土耳其總統確立,[23]但十年之限仍被批評太短。[24]2022年出現了許多太陽能-風能混合許可證被申請。[25]截止至2022年,共有九個可再生能源合作社;[26]有人建議如果農民在建立農業合作社時可以獲得更多貸款與技術支持,合作社或將有利可圖。[27]

據智庫Ember表示,建設新的風力發電和太陽能發電廠比運行現有需依賴進口煤碳的煤電廠還要便宜,[13]但是他們也表示了建設公用事業規模的太陽發電廠存在障礙,包括變壓器上並未給太陽能發電分配新容量,[28] 任何單個太陽能發電廠的裝機容量上限為50MW,以及大型客戶無法為新式無證太陽能裝置簽署長期購電協議。[13][18]對此Ember建議道,土耳其應強制要求新建築都要有屋頂太陽能板。[15]這樣一來,一些未經許可的小型裝置所有者就可以用和購買相同的價格向電網出售電力。[18]

經濟學

[編輯]

與許多國家應對間歇性可再生能源之做法一樣,土耳其政府時不時邀請企業進行秘密競投,藉以建設具有一定容量的太陽能發電站,並將其連接到某些變電站。在政府決定好最低價格後,就會承諾在固定年限內以該價格購買每千瓦·時電力,或者購買一定總量的電力──這些措施讓投資者在面對波動激烈的批發電價時能夠提供確定性。[29][30][31]不過如果他們以外幣來進行借款的話,仍然可能會面臨匯率波動的風險,[32]比如,鑒於土耳其沒有足夠的太陽能電池產能,該電池可能需另外從中國進口,是以他們必須使用外幣來支付。[33]在2022至23年間,中國共有三分之一的太陽能電池被出口至土耳其。[34]

2021年,這些「太陽能拍賣」之價格與平均批發電價相近或者更低,企業自用的大型太陽能發電裝置也具有一定競爭力;儘管如此廣泛的經濟挑戰與匯率波動仍帶來一些不穩定性。[35](p. 63)由於其安裝的成本低,[36]根據土耳其太陽能行業協會稱,該行業為十萬人提供了新的就業機會。[37]第四輪太陽能拍賣計劃總計為1000 MW,每批為50 MW和100 MW,[38]其中2022年4月就拍賣了三匹100 MW,價格約為每MWh 400土耳其里拉,[39]按照當時匯率來看相當於約25歐元。[40]由於該次招標包含60%的外匯權重條款,這在一定程度上防止了貨幣波動,[40]同時也允許在公開市場上銷售。[38]

據碳追蹤器的模型顯示,2023年新建的太陽能發電廠將比現有的所有煤電廠都還便宜。[41][42]根據智庫Ember在2022年5月的一份報告,風能與太陽能在過去的12個月中節省了70億美元的天然氣進口費用。[28]每安裝一GW太陽能發電設備,就可節省一億多美元的天然氣進口成本。[9]根據舒拉公司在2022年的一項研究顯示,到了20230年,幾乎所有煤電都將被可再生能源(主要為太陽能)取代。[43]太陽發電的出口最終會和與乾淨電力所生產的氫氣一同增加。[44]聚光太陽能發電的運行與維護成本約為2 UScent/kWh。[45](p. 132)在降低電價的同時,超過一定水平的太陽能發電量往往可以穩定電價。[46]

供暖與熱水

[編輯]自2019年以來,真空管集熱器之銷量已然超越平板集熱器。[1][6](p. 139)與平板相比,真空管的家用效率更高。[47]土耳其的太陽能熱水器集熱器容量位居世界第二,僅次於中國,[6](p. 41)其約2600萬平方米的集熱器每年可以產生115萬噸油當量之熱能。[1]使用者大約三分之二是家用,三分之一是工業用。[1]目前已安裝的生活熱水系統通常為對流式,無水汞,配有兩個平板集熱器,每個面積將近二平方米。[1]別墅與酒店現也開始安裝太陽能組合供暖系統(以燃氣為輔助之空間和水供暖系統)。[1]

該行業在供應熱水方面非常發達,其擁有高質量的製造與出口能力,但在空間供暖方面卻是不盡人意,而且其還受到煤炭供暖補貼的阻礙。[48](p. 36)2018年的一項研究發現,太陽能熱水器平均節能13%,並能提高房產價值。[49]

2021年,國際能源機構建議土耳其政府支持太陽能熱水器,因為「技術與基礎設施質量需要大幅提高,才能最大限度的發揮其潛力」。[35]

在土耳其,太陽能加熱也可用於農業上,比如用太陽能空氣加熱器烘乾農作物。[1]

2010年代,太陽能太陽能光電產業的發展得到了土耳其政府的支持。[35]其月平均效率為12-17%,詳細則取決於傾斜度與氣候類型;具體產量則隨着海拔的升高而降低。[51]2020年,土耳其開始生產太陽能電池,[52]2022年,能源與自然資源部部長法提赫·鄧梅茲聲稱,土耳其每年生處裝的太陽能光電模組足以生產8 GW的電力。[53]工業界有時會在需要大量電力的工藝(比如電解)中使用自己的太陽能,[54]然而與歐盟不同的是,截止至2020年,過時的太陽能電板不會被歸為電子垃圾,也沒有規定的回收標準。[55]有人建議可以在公共充電站安裝太陽能太陽能光電發電系統。[56]根據估計,土耳其太陽能光電發電的溫室氣體排放量為:太陽能公用事業規模約30克 Co2eq/千瓦·時,屋頂發現則為30克。[57]

太陽能發電廠

[編輯]土耳其最大的太陽能發電廠位於卡拉皮納爾太陽能發電廠,其在2020年開始發電,並計劃在2022年底將發電量超過一GW。[58][59]如果運作期間的太陽能發電站有一年不清潔,其效率就會降低5%以上。[60]環保組織稱,土耳其有一半的褐煤露天礦場可以改建成13 GW的太陽能發電廠(其中有些配有電池儲能電置),年發電量可達19 TWh,因為鄰近的22個褐煤發電站中的十GW發電站的大部分奠立基礎設施已經到位。[61]鋁生產商就很青睞於太陽能,因為他們在電解過程須用到大量電力。[62]

屋頂用太陽能板

[編輯]截止至2022年,屋頂太陽能發電量約為一GW,[63]許多企業也正在大量安裝,[64]土耳其政府的目標是在2030年達到二至四GW。[65]不過,如若太陽能電池板的總發電量已經超過當地配電變壓器容量的50%,該地區將不再批准建造更多的太陽能電池板。[65]

住宅用

[編輯]每戶的使用限額為10 GW。[17]然而其投資的回收期很長,因為從電網向住戶供電需要大量的補貼支持。截止至2019年,業主與企業使用淨計量屋頂太陽能的投資回收期估計為11年,是以有人建議取消增值稅與固定的政府審批費用,並將安裝借款與房產抵押掛勾,藉以縮短安裝時間。[66]

非住宅用

[編輯]一般來說,非住宅用電網之電價比住宅用電網之電價高,因此其投資回收期相對短很多。從2023年起,面積超過5000萬平方米的新建築必須至少要有5%的能源來自可再生能源。[67]2021年在安卡拉的一項研究發現,公共建築與商業建築的潛力遠遠大於住宅建築。[68]該研究還建議透過在新建築中採用合適的屋頂設計來提高技術潛力。[68]在地中海地區,太陽能太陽能光電發電若與熱汞一起使用,可能會使建築能夠實現零能耗。[69]鋁生產商托斯亞里控股公司聲稱將於2022年在其建築物屋頂安裝世界上最大的屋頂太陽能發電系統。[70]

農業

[編輯]農民安裝太陽能電池板能獲得資金支持,比如可以為灌溉水汞供電,並可出售部分電力。[71][72]有人建議農業光電技術可以適用於小麥、[73]玉米及一些喜蔭性植物。[74]有人建議將太陽能與沼氣一同使用(比如乳牛場)。[75]有人則建議可以收集雨水。[60]

太陽能光電發電的替代選擇

[編輯]

能源與自然資源部的穆罕默德·布魯特在2021年建議,可以在東南部將聚光太陽能熱發電(CSP)與太陽能光電發電在同一地點共同使用。[76]CSP系統是利用透鏡或反射鏡將太陽光反射到中央接收器上,將光轉化為熱量,再將熱量至轉化為電能,從而產生電力。土耳其的第一座太陽能發電塔乃位於梅爾辛的Greenway CSP 梅爾辛太陽能塔式發電廠,其裝機功率為五GW。[77]此外另有建議說可在安塔利亞省建立一座太陽能上升氣流塔。[78]

相關條目

[編輯]延伸閱讀

[編輯]- Turkey: Status of Solar Heating/Cooling and Solar Buildings – 2021. www.iea-shc.org. [2022-05-17]. (原始內容存檔於2023-04-03).

參考來源

[編輯]- ^ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 Turkey Country Report. International Energy Agency Solar heating and cooling. 2021 [2022-05-17]. (原始內容存檔於2023-04-03).

- ^ Acaroğlu, Hakan; García Márquez, Fausto Pedro. A life-cycle cost analysis of High Voltage Direct Current utilization for solar energy systems: The case study in Turkey. Journal of Cleaner Production. 2022-05-08, 360: 132128. ISSN 0959-6526. doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2022.132128

(英語).

(英語).

- ^ Dawood, Kamran. Hybrid wind-solar reliable solution for Turkey to meet electric demand. Balkan Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering. 2016, 4 (2): 62–66 [2024-01-26]. doi:10.17694/bajece.06954. (原始內容存檔於2023-04-03).

- ^ Solar power installed capacity tops 10,000 MW. Hürriyet Daily News. 2023-05-29 [2023-06-15]. (原始內容存檔於2023-10-14) (英語).

- ^ 存档副本. [2024-01-26]. (原始內容存檔於2021-12-19).

- ^ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Renewables Global Status Report. REN21. [2020-09-30]. (原始內容存檔於2019-05-24).

- ^ Overview of the Turkish Electricity Market (報告). PricewaterhouseCoopers. October 2021 [2021-11-28]. (原始內容存檔於2021-11-28).

- ^ 2022 energy outlook (PDF). Industrial Development Bank of Turkey. [2024-01-26]. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2023-04-20).

transferring money from solar, wind and hydroelectric power plants with low operating costs to power plants with high operating costs such as imported coal and natural gas

- ^ 9.0 9.1 Solar is key in reducing Turkish gas imports. Hürriyet Daily News. 2020-02-19 [2020-09-20]. (原始內容存檔於2020-04-06).

- ^ Matalucci, Sergio. Turkey targets Balkans and EU renewables markets. Deutsche Welle. 2022-03-30 [2022-05-19]. (原始內容存檔於2024-01-23) (英國英語).

- ^ Başgül, Erdem. Hot Topics In Turkish Renewable Energy Market. Mondaq. 2022-05-16 [2022-05-17]. (原始內容存檔於2023-12-11).

- ^ Todorović, Igor. Hybrid power plants dominate Turkey's new 2.8 GW grid capacity allocation. Balkan Green Energy News. 2022-03-08 [2022-07-07]. (原始內容存檔於2022-03-08) (美國英語).

- ^ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Turkey: New wind and solar power now cheaper than running existing coal plants relying on imports. Ember. 2021-09-27 [2021-09-29]. (原始內容存檔於2021-09-29) (英國英語).

- ^ Türkiye Electricity Review 2023. Ember. 2023-03-13 [2023-03-29]. (原始內容存檔於2024-03-09) (美國英語).

- ^ 15.0 15.1 Türkiye can expand solar by 120 GW through rooftops. Ember. 2023-12-11 [2023-12-28]. (原始內容存檔於2024-02-29) (美國英語).

- ^ 16.0 16.1 Solar. Republic of Turkey Ministry of Energy and Natural Resources. [2020-09-12]. (原始內容存檔於2021-01-24).

- ^ 17.0 17.1 17.2 Çeçen, Mehmet; Yavuz, Cenk; Tırmıkçı, Ceyda Aksoy; Sarıkaya, Sinan; Yanıkoğlu, Ertan. Analysis and evaluation of distributed photovoltaic generation in electrical energy production and related regulations of Turkey. Clean Technologies and Environmental Policy. 2022-01-07, 24 (5): 1321–1336. ISSN 1618-9558. PMC 8736286

. PMID 35018170. doi:10.1007/s10098-021-02247-0 (英語).

. PMID 35018170. doi:10.1007/s10098-021-02247-0 (英語).

- ^ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 Turkey take the winding road to solar success. Norton Rose Fulbright. February 2020 [2022-03-21]. (原始內容存檔於2023-04-05) (英語).

- ^ The Sky's the Limit: Solar and wind energy potential. Carbon Tracker Initiative. [2021-05-01]. (原始內容存檔於2021-04-30).

- ^ O'Byrne, David. Turkey faces double whammy as low hydro aligns with gas contract expiries. S & P Global. 2021-08-09 [2022-03-17]. (原始內容存檔於2022-03-17) (英語).

- ^ Non-hydro renewables overtake hydro for first time. Hürriyet Daily News. 2022-01-22. (原始內容存檔於2023-09-30) (英語).

- ^ Türkiye to increase energy investments with zero emission target. Hürriyet Daily News. 2023-01-21 [2023-01-21]. (原始內容存檔於2023-01-24) (英語).

- ^ Amendments In The Law On Utilization Of Renewable Energy Sources For The Purpose Of Generating Electrical Energy. Mondaq. [2020-12-26]. (原始內容存檔於2022-02-19).

- ^ Kılıç, Uğur; Kekezoğlu, Bedri. A review of solar photovoltaic incentives and Policy: Selected countries and Turkey. Ain Shams Engineering Journal. 2022-09-01, 13 (5): 101669. ISSN 2090-4479. S2CID 246212766. doi:10.1016/j.asej.2021.101669

(英語).

(英語).

- ^ 2021 was record year for annual wind installations in Turkey. Balkan Green Energy News. 2022-01-06 [2022-01-21]. (原始內容存檔於2022-01-21) (美國英語).

- ^ Türkiye'deki güneş enerjisi kooperatifleri, ithal enerji yüküne ne kadar çözüm olabilir? [How much can solar energy cooperatives in Turkey relieve the imported energy burden?]. BBC News Türkçe. [2022-05-14]. (原始內容存檔於2023-06-21) (土耳其語).

- ^ Everest, Bengü. Willingness of farmers to establish a renewable energy (solar and wind) cooperative in NW Turkey. Arabian Journal of Geosciences. 2021-03-15, 14 (6): 517. ISSN 1866-7538. PMC 7956873

. doi:10.1007/s12517-021-06931-9 (英語).

. doi:10.1007/s12517-021-06931-9 (英語).

- ^ 28.0 28.1 Turkey: Wind and solar saved $7 bn in 12 months. Ember. 2022-05-24 [2022-05-26]. (原始內容存檔於2022-05-24) (美國英語).

- ^ Renewable Energy Auctions Toolkit | Energy | U.S. Agency for International Development. USAID. 2021-07-28 [2022-05-19]. (原始內容存檔於2023-12-05) (英語).

- ^ Feed-In Tariffs vs Reverse Auctions: Setting the Right Subsidy Rates for Solar. Development Asia. 2021-11-10 [2022-05-19]. (原始內容存檔於2024-03-04) (英語).

- ^ Government hits accelerator on low-cost renewable power. UK government. [2022-05-19]. (原始內容存檔於2024-06-12) (英語).

- ^ Currency Risk Is the Hidden Solar Project Deal Breaker. greentechmedia.com. [2022-05-19]. (原始內容存檔於2024-03-05).

- ^ Regional distribution of solar module production. Statista. [2022-05-19]. (原始內容存檔於2024-07-08) (英語).

- ^ Solar exports from China increase by a third. 2023-09-13 [2024-01-27]. (原始內容存檔於2024-07-25).

- ^ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Renewables 2021 – Analysis. International Energy Agency. [2021-12-03]. (原始內容存檔於2021-12-03) (英國英語).

- ^ Turkey. climateactiontracker.org. [2022-05-01]. (原始內容存檔於2018-06-14) (英語).

- ^ Sırt, Timur. Technology, retail giants embrace solar power. Daily Sabah. 2022-03-18 [2022-03-21]. (原始內容存檔於2023-04-05) (美國英語).

- ^ 38.0 38.1 Terms of Reference regarding the YEKA-GES-4 Auction are Changed. gonen.com.tr. [2022-04-17]. (原始內容存檔於2023-04-04).

- ^ YEKA GES 4 Yarışma Sonuçları-8 Nisan 2022 – Güneş. Solarist – Güneş Enerjisi Portalı. 2022-04-08 [2022-04-17]. (原始內容存檔於2023-04-04) (土耳其語).

- ^ 40.0 40.1 Turkey completes solar power auction for 300 MW. Balkan Green Energy News. 2022-04-11 [2022-04-17]. (原始內容存檔於2023-12-05) (美國英語).

- ^ Global Coal Power Economics Model Methodology (PDF). Carbon Tracker. [2022-01-21]. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2020-03-21).

- ^ Wind vs Coal power in Turkey/Solar PV vs Coal in Turkey (PDF). Carbon Tracker. 2020 [2022-01-21]. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2020-03-18).

- ^ Integration of Renewable Energy into the Turkish Electricity System. Shura. 2022-04-28 [2022-05-17]. (原始內容存檔於2024-04-15) (美國英語).

- ^ Chandak, Pooja. Turkey is Very Important for Energy Diversification plans of the European Union Says EU Minister. SolarQuarter. 2022-05-04 [2022-05-19]. (原始內容存檔於2023-04-05) (英國英語).

- ^ Renewable Power Generation Costs in 2021. /publications/2022/Jul/Renewable-Power-Generation-Costs-in-2021. 2022-07-13 [2022-07-26]. (原始內容存檔於2024-07-10) (英語).

- ^ 存档副本. [2024-01-28]. (原始內容存檔於2024-01-28).

- ^ Siampour, Leila; Vahdatpour, Shoeleh; Jahangiri, Mehdi; Mostafaeipour, Ali; Goli, Alireza; Shamsabadi, Akbar Alidadi; Atabani, Abdulaziz. Techno-enviro assessment and ranking of Turkey for use of home-scale solar water heaters. Sustainable Energy Technologies and Assessments (Elsevier). 2021-02-01, 43: 100948. ISSN 2213-1388. doi:10.1016/j.seta.2020.100948

(英語).

(英語).

- ^ Turkey 2019. Environmental Performance Reviews. OECD Environmental Performance Reviews (OECD). February 2019. ISBN 9789264309746. S2CID 242969625. doi:10.1787/9789264309753-en.

- ^ Aydin, Erdal; Eichholtz, Piet; Yönder, Erkan. The economics of residential solar water heaters in emerging economies: The case of Turkey. Energy Economics. 2018-09-01, 75: 285–299 [2021-01-03]. ISSN 0140-9883. S2CID 158839915. doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2018.08.001. (原始內容存檔於2020-06-12) (英語).

- ^ Renewable Energy Engineering, Research and Applications Center. Karabük University. [2022-05-17].

- ^ Ozden, Talat. A countrywide analysis of 27 solar power plants installed at different climates. Scientific Reports. 2022-01-14, 12 (1): 746. Bibcode:2022NatSR..12..746O. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 8760320

. PMID 35031638. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-04551-7 (英語).

. PMID 35031638. doi:10.1038/s41598-021-04551-7 (英語).

- ^ Bir, Burak; Aliyev, Jeyhun. Turkey to open 1st domestic solar panel factory in Aug.. Anadolu Agency. 2020-07-05 [2020-07-06]. (原始內容存檔於2020-07-07).

- ^ Dönmez: Turkey is world's No. 4 solar panel producer. Balkan Green Energy News. 2022-05-06 [2022-05-09]. (原始內容存檔於2024-05-20) (美國英語).

- ^ Turkish aluminum producer building solar power plants to reach net zero emissions. Balkan Green Energy News. 2022-02-02 [2022-03-07]. (原始內容存檔於2022-03-08) (美國英語).

- ^ Erat, Selma; Telli, Azime. Within the global circular economy: A special case of Turkey towards energy transition. MRS Energy & Sustainability. 2020, 7 (1): 24. ISSN 2329-2229. PMC 7849225

. doi:10.1557/mre.2020.26

. doi:10.1557/mre.2020.26  (英語).

(英語).

- ^ Turan, Mehmet Tan; Gökalp, Erdin. Integration Analysis of Electric Vehicle Charging Station Equipped with Solar Power Plant to Distribution Network and Protection System Design. Journal of Electrical Engineering & Technology. 2022-03-01, 17 (2): 903–912. Bibcode:2022JEET...17..903T. ISSN 2093-7423. S2CID 244615183. doi:10.1007/s42835-021-00927-x

(英語).

(英語).

- ^ Kursun, Berrin. Role of solar power in shifting the Turkish electricity sector towards sustainability. Clean Energy (Oxford University Press). 2022-04-09, 6 (2): 1078–1089. doi:10.1093/ce/zkac002.

- ^ GE Renewable Energy and Kalyon to power Turkey with 1.3 GW solar projects. TR MONITOR. 2021-09-23 [2021-09-26]. (原始內容存檔於2021-09-26) (美國英語).

- ^ Category A project supported: Kaparinar Yeka (Kalyon) Solar Power Plant, Turkey. GOV.UK. [2022-03-07]. (原始內容存檔於2022-03-07) (英語).

- ^ 60.0 60.1 Şevik, Seyfi; Aktaş, Ahmet. Performance enhancing and improvement studies in a 600kW solar photovoltaic power plant; manual and natural cleaning, rainwater harvesting and the snow load removal on the PV arrays. Renewable Energy. 2022-01-01, 181: 490–503. ISSN 0960-1481. S2CID 239336676. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2021.09.064 (英語).

- ^ Turkey's open-cast coal mines can host enough solar to power almost seven million homes. Europe Beyond Coal. 2022-03-23 [2022-03-24]. (原始內容存檔於2023-03-17) (美國英語).

- ^ Todorović, Igor. Turkish aluminum producer building solar power plants to reach net zero emissions. Balkan Green Energy News. 2022-02-02 [2024-01-28]. (原始內容存檔於2022-03-08).

- ^ GÜNDER Yönetim Kurulu Başkanı Kaleli: Çatı tipi güneş santrali pazarında başvuru sayısı 2 bini geçti [Solar Association Chairman Kaleli: More than 2000 solar rooftop applications]. Anadolu Agency. [2022-03-07]. (原始內容存檔於2022-03-07) (土耳其語).

- ^ Turkish Companies Go Solar at Record Pace to Cut Energy Costs. Bloomberg.com. 2022-12-01 [2022-12-03]. (原始內容存檔於2022-12-16) (英語).

- ^ 65.0 65.1 Solar photovoltaics in CEE: Prospects for installation & utilization. cms.law. [2022-03-07]. (原始內容存檔於2022-03-07) (英語).

- ^ Flora, Arjun; Özenç, Bengisu; Wynn, Gerard. New Incentives Brighten Turkey's Rooftop Solar Sector (PDF). Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis. December 2019 [2019-12-21]. (原始內容存檔 (PDF)於2019-12-21).

- ^ Buildings to be required to use renewable energy. Hürriyet Daily News. 2022-02-20 [2022-03-07]. (原始內容存檔於2022-03-07).

- ^ 68.0 68.1 Kutlu, Elif Ceren; Durusoy, Beyza; Ozden, Talat; Akinoglu, Bulent G. Technical potential of rooftop solar photovoltaic for Ankara. Renewable Energy. 2022-02-01, 185: 779–789. ISSN 0960-1481. S2CID 245392035. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2021.12.079 (英語).

- ^ Zaferanchi, Mahdiyeh; Sozer, Hatice. Effectiveness of interventions to convert the energy consumption of an educational building to zero energy. International Journal of Building Pathology and Adaptation (Emerald Publishing Limited). 2022-01-01. ISSN 2398-4708. S2CID 247355490. doi:10.1108/IJBPA-08-2021-0114.

- ^ Turkish aluminum producer Tosyalı launches world's biggest rooftop solar project. Balkan Green Energy News. 2022-03-23 [2022-04-17]. (原始內容存檔於2024-02-25) (美國英語).

- ^ Todorović, Igor. Turkey to grant 40% to farmers for solar power systems – report. Balkan Green Energy News. 2022-03-18. (原始內容存檔於2023-12-05) (美國英語).

- ^ Son dakika… Bakan Nebati: 15 yılda tamamlanacak projeleri 2 yılda bitireceğiz. Hürriyet. 2022-03-21 [2022-03-23]. (原始內容存檔於2023-04-04) (土耳其語).

- ^ Parkinson, Simon; Hunt, Julian. Economic Potential for Rainfed Agrivoltaics in Groundwater-Stressed Regions. Environmental Science & Technology Letters. 2020-07-14, 7 (7): 525–531 [2024-01-28]. ISSN 2328-8930. S2CID 225824571. doi:10.1021/acs.estlett.0c00349. (原始內容存檔於2023-04-04) (英語).

- ^ Atıl Emre, Coşgun. The potential of Agrivoltaic systems in Turkey. Energy Reports. 2021-06-16, 7: 105–111. ISSN 2352-4847. doi:10.1016/j.egyr.2021.06.017

(英語).

(英語).

- ^ Kirim, Yavuz; Sadikoglu, Hasan; Melikoglu, Mehmet. Technical and economic analysis of biogas and solar photovoltaic (PV) hybrid renewable energy system for dairy cattle barns. Renewable Energy. 2022-04-01, 188: 873–889. ISSN 0960-1481. S2CID 247114342. doi:10.1016/j.renene.2022.02.082 (英語).

- ^ Bulut, Mehmet. Integrated solar power project based on CSP and PV technologies for Southeast of Turkey. International Journal of Green Energy (Informa UK Limited). 2021-07-19, 19 (6): 603–613 [2022-01-24]. ISSN 1543-5075. S2CID 237718860. doi:10.1080/15435075.2021.1954006. (原始內容存檔於2022-03-18).

- ^ Benmayor, Gila. Solar tower at Mersin. Hürriyet Daily News. 2013-04-23 [2014-02-10]. (原始內容存檔於2017-02-20).

- ^ Ikhlef, Khaoula; Üçgül, İbrahim; Larbi, Salah; Ouchene, Samir. Performance estimation of a solar chimney power plant (SCPP) in several regions of Turkey. Journal of Thermal Engineering. 2022, 8 (2): 202 [2024-01-28]. doi:10.18186/thermal.1078957 (不活躍 1 August 2023). (原始內容存檔於2023-04-05) (英語).

外部連結

[編輯]- 土耳其太陽能行業協會 (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館)

- 國際太陽能協會土耳其分會 (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館)

- 土耳其暖通空調與衛生工程師協會(TTMD) (頁面存檔備份,存於互聯網檔案館)