环孢素

| |

| |

| 临床资料 | |

|---|---|

| 读音 | /ˌsaɪkləˈspɔːrɪn/[1] |

| 商品名 | Sandimmune及其他 |

| 其他名称 | cyclosporin、ciclosporin A,[2]cyclosporine A及cyclosporin A (CsA), cyclosporine (USAN US) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a601207 |

| 核准状况 | |

| 怀孕分级 |

|

| 给药途径 | 口服给药, 静脉注射,眼药水 |

| 药物类别 | 钙调磷酸酶抑制剂 |

| ATC码 | |

| 法律规范状态 | |

| 法律规范 |

|

| 药物动力学数据 | |

| 生物利用度 | 并非固定 |

| 药物代谢 | 肝脏 CYP3A4 |

| 生物半衰期 | 并非固定 (约24小时) |

| 排泄途径 | 胆管 |

| 识别信息 | |

| |

| CAS号 | 59865-13-3 |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB配体ID | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.119.569 |

| 化学信息 | |

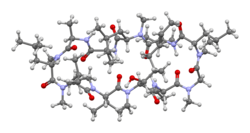

| 化学式 | C62H111N11O12 |

| 摩尔质量 | 1,202.64 g·mol−1 |

| 3D模型(JSmol) | |

| |

| |

环孢素(英语:ciclosporin,也有cyclosporine及cyclosporin的拼写法),是一种钙调磷酸酶抑制剂,作为免疫抑制剂之用,以治疗类风湿性关节炎、干癣、克隆氏症、肾病症候群、湿疹,以及作为器官移植后长期服用之药物,防止移植器官受到排斥。[13][14]此药物透过口服或是静脉注射方式给药,也制成眼药水形式以治疗干眼症。[15]

使用后常见的副作用有高血压、头痛、肾脏问题、毛发生长增加和呕吐。[14]严重的副作用有感染风险增加、肝脏问题和罹患淋巴瘤风险增加。[14]使用后应持续检查药物的血药浓度以降低副作用风险。[14]个体于怀孕期间使用可能会导致早产,但此药物似乎不会造成胎儿的先天性障碍。[16]

环孢素被认为是透过降低淋巴球的功能来发挥作用。[14]它与亲环蛋白形成复合物来阻断钙调磷酸酶的磷酸酶活性,而减少T细胞产生促炎性细胞因子。[17]

环孢素于1971年从名为膨大弯颈霉的真菌分离出,并于1983年取得核准用于医疗用途。[18]它已列入世界卫生组织基本药物标准清单之中。[19][20]此药物在美国于2022年最常使用处方药中排名第185,开立的处方笺数量超过200万张。[21][22]市面上有其通用名药物流通。[23]

医疗用途

[编辑]环孢素用于治疗和预防造血干细胞移植(又称骨髓移植)的移植物对抗宿主疾病,并预防宿主对于移植而来的肾脏、心脏和肝脏的排斥反应。[7][6]此药物也在美国被批准用于治疗类风湿性关节炎和干癣、腺病毒性角结膜炎后出现的持续性钱币状角膜炎,[24][6]以及作为治疗干燥症和睑板腺功能障碍引起的干眼症之用的眼药水。[8]

环孢素除这些适应症外,也用于治疗严重的异位性皮肤炎,[25]及严重的类风湿性关节炎及相关疾病。[26]

环孢素也用于治疗对类固醇治疗无反应的急性严重溃疡性结肠炎和荨麻疹患者。[27]

副作用

[编辑]使用环孢素产生的副作用有牙龈肿大、毛发生长增加、抽搐、消化性溃疡、胰腺炎、发烧、呕吐、腹泻、精神错乱、胆固醇升高、呼吸困难、麻木和刺痛(尤其是嘴唇)、搔痒、高血压、钾滞留(可能导致高血钾症)、肾脏和肝功能障碍、[28]指尖灼热感,以及容易受到霉菌和病毒感染。环孢素会诱导肾脏血管收缩和增加钠重吸收,而引起高血压。血压升高会引发心血管问题,因此建议需要使用此药物进行长期治疗的人只使用最低的有效剂量。[29]

肾脏移植后使用环孢素与血液中尿酸浓度升高有关,在某些情况下也会导致痛风。[30]

环孢素被列为国际癌症研究机构一类致癌物(即有足够的证据表明对人类具有致癌性),[31]特别是会导致皮肤鳞状细胞癌和非霍奇金氏淋巴瘤。[32]

药理学

[编辑]作用机转

[编辑]环孢素的主要作用是降低T细胞的活性,它透过抑制钙调磷酸酶-磷酸酶途径中的钙调磷酸酶,并阻止线粒体通透性转变孔(MPTP)打开来达成。环孢素借由阻止活化T细胞核因子去磷酸化,导致效应性T细胞功能降低[33][34][35][36]

环孢素是一种免疫抑制剂,除抑制免疫反应外,还能与线粒体膜上的线粒体通透性转变孔结合。[34][37]MPTP是细胞能量工厂(线粒体)上的一各通道,其开闭程度直接影响细胞的能量供应。环孢素能稳定MPTP的状态,防止其过度开启,而保护细胞免受能量耗竭的损害。[38]

环孢素可减缓肾脏微小病变和局灶节段性肾小球硬化症等疾病引起的蛋白尿。其机制为:环孢素保护足细胞中的突触足蛋白,使其不被分解,进而维持肾小球基底膜的完整性,减少蛋白质流失。[39]

药物动力学

[编辑]环孢素是一种由11个氨基酸组成的环肽,它有单一的D-氨基酸,在自然界中很少见。环孢素并非由核糖体合成,与大多数的肽不同。[40]

环孢素经摄入后会在人类和动物体内充分代谢。代谢物包括环孢素B、C、D、E、H和L,[41]代谢物的免疫抑制活性不到原形环孢素的10%,且与较高的肾毒性有关联。[42]

生物合成

[编辑]

非核糖体肽合成酶经由活化、连接和修饰氨基酸,逐步合成环孢素。[43]

基因簇

[编辑]目前用于大量生产环孢素的物种 - 膨大弯颈霉 - 的生物合成基因排列,形成一个12个基因的簇。这12基因簇是此霉菌生产环孢素的重要遗传基础,基因间相互协作,共同完成环孢素的合成过程。[44][45][46][47]

历史

[编辑]于瑞士巴塞尔桑多兹集团公司(现已并入诺华制药)服务的科学家于1970年从挪威和美国威斯康辛州采集的土壤样本中分离出新的真菌菌株。两种菌株都会产生一系列称为环孢素的天然产物,均具有抗真菌活性的成分。来自挪威的菌株 - 膨大弯颈霉 - 后来被用于大规模生产环孢素。[48]

天然环孢素的免疫抑制作用于1972年1月31日[49]被于桑多兹集团服务的药理学家哈特曼·F·斯塔赫林发现。[50][48]环孢素的化学结构于1976年也为桑多兹集团确定。[51][52]后来英国外科医师罗伊·约克·卡恩爵士及其剑桥大学的同事在1978年进行的肾脏移植手术中[53]以及美国外科医师托马斯·斯塔尔兹于1980年在匹兹堡大学医疗中心儿童医院进行的肝脏移植手术中[54]均成功确定环孢素具有预防移植排斥的作用。 美国食品药物管理局(FDA)于1983年核准环孢素用于医疗用途。[55][56][57][58]

托马斯·斯塔尔兹在其撰述的回忆录中解释环孢素是实体器官同种异体移植的划时代药物,[59]其具有的良好抗排斥治疗成分,大幅扩展移植手术的临床适用性。[59]简而言之,广泛应用这种移植的最大限制不是成本或手术技术,而是同种异体移植排斥以及捐赠器官来源稀缺的问题。环孢素则在处理排斥方面获得重大进展。[59]

社会与文化

[编辑]法律地位

[编辑]欧洲药品管理局人用药品委员会(CHMP)于2024年7月采纳正面意见,建议授予用于治疗干眼症药品Vevizye的上市许可。药品的申请者是设于德国的Novaliq GmbH。[11]Vevizye于2024年9月取得欧盟核准用于医疗用途。[11]

名称

[编辑]这种天然产物被首先分离出来的科学家命名为cyclosporin,[48]而在翻译成英文后将名称改写为cyclosporine。根据国际非专有药名 (INN) 命名指南,药物名称再进而改为ciclosporin。[60]

INN和英国批准名称 (BAN)均采用Ciclosporin名称,而美国采用名称 (USAN),则使用cyclosporin 。[61]

销售配方

[编辑]环孢素的水溶解度非常差,因此药厂开发出的是供口服和注射用的悬浮液和乳液形式。桑多兹集团最初推出产品的商品名为Sandimmune,有软明胶胶囊、口服溶液和静脉注射制剂等形式。[7]一种较新的微乳液[62]口服制剂<Neoralref name="Neoral FDA label" />为溶液和软明胶胶囊形式。 [63][64]

此药物的通用名药物已有各种品牌名称于市面出现,包括 Cicloral、Gengraf和Deximune。一种用于治疗干燥性角结膜炎(干眼症)引起发炎的环孢素外用乳剂于2002年以Restasis品牌上市。 吸入式的环孢素制剂正在临床开发中。[65][66]

研究

[编辑]神经保护

[编辑]环孢素正在欧洲进行一项II/III期(适应性)临床研究,以确定其对创伤性脑损伤中改善神经元细胞损伤和缺血再灌流伤害(III期)的能力。

环孢素已被研究作为脑外伤等情况下可能的神经保护剂,并在动物实验中显示可减少与损伤所造成的相关脑损伤。[67]

心脏病

[编辑]环孢素已在实验中用于治疗心脏肥大(细胞体积增加)。[34][68]

环孢素已被证明可透过多种方式影响心肌细胞来减少心脏肥大。

兽医用途

[编辑]该药物在美国被批准用于治疗狗的异位性皮肤炎。狗身上使用的剂量较人类为少,表示此药物可作为免疫调节剂,并且比发生在人类身上的副作用更少。本产品有助于减少控制病情所需的药物种类。也有含环孢素的狗用眼药膏(Optimmune)及用于治疗狗的皮脂腺炎、落叶型天疱疮、发炎性肠道疾病、肛门疖病和重症肌无力的环孢素药物。[69][70]

参考文献

[编辑]- ^ cyclosporin. Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House. n.d. [13 July 2011]. (原始内容存档于18 November 2010).

- ^ Laupacis A, Keown PA, Ulan RA, McKenzie N, Stiller CR. Cyclosporin A: a powerful immunosuppressant. Canadian Medical Association Journal. May 1982, 126 (9): 1041–6. PMC 1863293

. PMID 7074504.

. PMID 7074504.

- ^ Regulatory Decision Summary for Restasis Multidose. Drug and Health Product Register. 2014-10-23 [2022-06-07]. (原始内容存档于2022-06-07).

- ^ Regulatory Decision Summary for Verkazia. Drug and Health Product Register. 2014-10-23 [2022-06-07]. (原始内容存档于2022-06-07).

- ^ Health product highlights 2021: Annexes of products approved in 2021. Health Canada. 2022-08-03 [2024-03-25].

- ^ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Neoral- cyclosporine capsule, liquid filled Neoral- cyclosporine solution. DailyMed. [2022-02-03]. (原始内容存档于2013-07-05).

- ^ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Sandimmune- cyclosporine capsule, liquid filled Sandimmune- cyclosporine injection Sandimmune- cyclosporine solution. DailyMed. [2022-02-03]. (原始内容存档于2014-04-21).

- ^ 8.0 8.1 Restasis- cyclosporine emulsion. DailyMed. [2022-02-03]. (原始内容存档于2014-03-30).

- ^ Vevye- cyclosporine ophthalmic solution solution/ drops. DailyMed. 2023-05-26 [2023-08-29]. (原始内容存档于2023-08-29).

- ^ Ikervis. European Medicines Agency. 2018-09-17 [27 February 2023]. (原始内容存档于13 August 2022).

- ^ 11.0 11.1 11.2 Vevizye EPAR. European Medicines Agency. 25 July 2024 [2024-07-27]. Text was copied from this source which is copyright European Medicines Agency. Reproduction is authorized provided the source is acknowledged.

- ^ Vevizye PI. Union Register of medicinal products. 2024-09-23 [2024-09-27].

- ^ World Health Organization. Stuart MC, Kouimtzi M, Hill SR , 编. WHO Model Formulary 2008. World Health Organization. 2009: 221. ISBN 9789241547659. hdl:10665/44053

.

.

- ^ 14.0 14.1 14.2 14.3 14.4 Cyclosporine. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. [2016-12-08]. (原始内容存档于2016-10-17).

- ^ Cyclosporine eent. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. [2016-12-08]. (原始内容存档于2016-01-13).

- ^ Cyclosporine Use During Pregnancy. Drugs.com. [2016-12-20]. (原始内容存档于2017-09-14).

- ^ Matsuda S, Koyasu S. Mechanisms of action of cyclosporine (PDF). Immunopharmacology. May 2000, 47 (2–3): 119–25 [2018-03-04]. PMID 10878286. doi:10.1016/S0162-3109(00)00192-2. (原始内容 (PDF)存档于2017-08-11).

- ^ Watts R, Clunie G, Hall F, Marshall T. Rheumatology. Oxford University Press. 2009: 558. ISBN 978-0-19-922999-4. (原始内容存档于2017-11-05).

- ^ World Health Organization. World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 21st list 2019. Geneva: World Health Organization. 2019. hdl:10665/325771

. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

. WHO/MVP/EMP/IAU/2019.06. License: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

- ^ World Health Organization. World Health Organization model list of essential medicines: 22nd list (2021). Geneva: World Health Organization. 2021. hdl:10665/345533

. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

. WHO/MHP/HPS/EML/2021.02.

- ^ The Top 300 of 2022. ClinCalc. [2024-08-30]. (原始内容存档于2024-08-30).

- ^ Cyclosporine Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022. ClinCalc. [2024-08-30].

- ^ FDA Approves First Generic of Restasis. U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (新闻稿). 2022-02-02 [2022-02-03]. (原始内容存档于2022-02-02).

- ^ Reinhard T. Lokales Cyclosporin A bei Nummuli nach Keratoconjunctivitis epidemica Eine Pilotstudie - Springer. Der Ophthalmologe. 2000, 97 (11): 764–768. PMID 11130165. S2CID 399211. doi:10.1007/s003470070025.

- ^ Paolino A, Alexander H, Broderick C, Flohr C. Non-biologic systemic treatments for atopic dermatitis: Current state of the art and future directions. Clinical and Experimental Allergy. May 2023, 53 (5): 495–510. PMID 36949024. doi:10.1111/cea.14301

.

.

- ^ Dijkmans BA, van Rijthoven AW, Goei Thè HS, Boers M, Cats A. Cyclosporine in rheumatoid arthritis. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism. August 1992, 22 (1): 30–36. PMID 1411580. doi:10.1016/0049-0172(92)90046-g.

- ^ Lichtiger S, Present DH, Kornbluth A, Gelernt I, Bauer J, Galler G, Michelassi F, Hanauer S. Cyclosporine in severe ulcerative colitis refractory to steroid therapy. The New England Journal of Medicine. June 1994, 330 (26): 1841–5. PMID 8196726. doi:10.1056/NEJM199406303302601

.

.

- ^ Naesens M, Kuypers DR, Sarwal M. Calcineurin inhibitor nephrotoxicity. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology (PDF) http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/content/4/2/481.full.pdf

|url=缺少标题 (帮助). February 2009, 4 (2): 481–508 [2018-04-20]. PMID 19218475. doi:10.2215/CJN.04800908 . (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2018-07-20).

. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2018-07-20).

- ^ Robert N, Wong GW, Wright JM. Effect of cyclosporine on blood pressure. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. January 2010, (1): CD007893. PMID 20091657. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007893.pub2.

- ^ Figg WD. Cyclosporine-induced hyperuricemia and gout. The New England Journal of Medicine. February 1990, 322 (5): 334–336. PMID 2296276. doi:10.1056/NEJM199002013220514

.

.

- ^ Agents Classified by the IARC Monographs, Volumes 1–110 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2011-10-25.

- ^ IARC Working Group on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risk to Humans. Ciclosporin. International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2012 [2018-02-23]. (原始内容存档于2021-08-28).

- ^ Ganong WF. 27. Review of medical physiology

22nd. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2005: 530. ISBN 978-0-07-144040-0.

22nd. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. 2005: 530. ISBN 978-0-07-144040-0.

- ^ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Mott JL, Zhang D, Freeman JC, Mikolajczak P, Chang SW, Zassenhaus HP. Cardiac disease due to random mitochondrial DNA mutations is prevented by cyclosporin A. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. July 2004, 319 (4): 1210–5. PMID 15194495. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.05.104.

- ^ Youn TJ, Piao H, Kwon JS, Choi SY, Kim HS, Park DG, Kim DW, Kim YG, Cho MC. Effects of the calcineurin dependent signaling pathway inhibition by cyclosporin A on early and late cardiac remodeling following myocardial infarction. European Journal of Heart Failure. December 2002, 4 (6): 713–8. PMID 12453541. S2CID 9181082. doi:10.1016/S1388-9842(02)00120-4

.

.

- ^ Handschumacher RE, Harding MW, Rice J, Drugge RJ, Speicher DW. Cyclophilin: a specific cytosolic binding protein for cyclosporin A. Science. November 1984, 226 (4674): 544–7. Bibcode:1984Sci...226..544H. PMID 6238408. doi:10.1126/science.6238408.

- ^ Elrod JW, Wong R, Mishra S, Vagnozzi RJ, Sakthievel B, Goonasekera SA, Karch J, Gabel S, Farber J, Force T, Brown JH, Murphy E, Molkentin JD. Cyclophilin D controls mitochondrial pore-dependent Ca(2+) exchange, metabolic flexibility, and propensity for heart failure in mice. Journal of Clinical Investigation. October 2010, 120 (10): 3680–7. PMC 2947235

. PMID 20890047. doi:10.1172/JCI43171.

. PMID 20890047. doi:10.1172/JCI43171.

- ^ Zorov DB, Juhaszova M, Sollott SJ. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ROS-induced ROS release. Physiological Reviews. July 2014, 94 (3): 909–50. PMC 4101632

. PMID 24987008. doi:10.1152/physrev.00026.2013.

. PMID 24987008. doi:10.1152/physrev.00026.2013.

- ^ Faul C, Donnelly M, Merscher-Gomez S, Chang YH, Franz S, Delfgaauw J, Chang JM, Choi HY, Campbell KN, Kim K, Reiser J, Mundel P. The actin cytoskeleton of kidney podocytes is a direct target of the antiproteinuric effect of cyclosporine A. Nature Medicine. 2008, 14 (9): 931–938. PMC 4109287

. PMID 18724379. doi:10.1038/nm.1857.

. PMID 18724379. doi:10.1038/nm.1857.

- ^ Borel JF. History of the discovery of cyclosporin and of its early pharmacological development. Wiener Klinische Wochenschrift. June 2002, 114 (12): 433–7. PMID 12422576.

Some sources list the fungus under an alternative species name Hypocladium inflatum gams such as Pritchard and Sneader in 2005:

* Pritchard DI. Sourcing a chemical succession for cyclosporin from parasites and human pathogens. Drug Discovery Today. May 2005, 10 (10): 688–91. PMID 15896681. doi:10.1016/S1359-6446(05)03395-7.

* Sneader W. Ciclosporin. Drug Discovery — A History . John Wiley & Sons. 2005-06-23: 298–299. ISBN 978-0-471-89979-2.

. John Wiley & Sons. 2005-06-23: 298–299. ISBN 978-0-471-89979-2.

However, the name, "Beauveria nivea", also appears in several other articles including in a 2001 online publication by Harriet Upton entitled "Origin of drugs in current use: the cyclosporin story 互联网档案馆的存档,存档日期2005-03-08." (retrieved 19 June 2005). Mark Plotkin states in his book Medicine Quest, Penguin Books 2001, pages 46-47, that in 1996 mycology researcher Kathie Hodge found that it is in fact a species of Cordyceps. - ^ Wang CP, Hartman NR, Venkataramanan R, Jardine I, Lin FT, Knapp JE, Starzl TE, Burckart GJ. Isolation of 10 cyclosporine metabolites from human bile. Drug Metabolism and Disposition. 1989, 17 (3): 292–6. PMC 3154783

. PMID 2568911.

. PMID 2568911.

- ^ Copeland KR, Yatscoff RW, McKenna RM. Immunosuppressive activity of cyclosporine metabolites compared and characterized by mass spectroscopy and nuclear magnetic resonance. Clinical Chemistry. February 1990, 36 (2): 225–9. PMID 2137384. doi:10.1093/clinchem/36.2.225

.

.

- ^ Lawen A. Biosynthesis of cyclosporins and other natural peptidyl prolyl cis/trans isomerase inhibitors. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. October 2015, 1850 (10): 2111–20. PMID 25497210. doi:10.1016/j.bbagen.2014.12.009.

- ^ Yang X, Feng P, Yin Y, Bushley K, Spatafora JW, Wang C. Tolypocladium inflatum Benefits Fungal Adaptation to the Environment. mBio. October 2018, 9 (5). PMC 6168864

. PMID 30279281. doi:10.1128/mBio.01211-18.

. PMID 30279281. doi:10.1128/mBio.01211-18.

- ^ Bushley KE, Raja R, Jaiswal P, Cumbie JS, Nonogaki M, Boyd AE, Owensby CA, Knaus BJ, Elser J, Miller D, Di Y, McPhail KL, Spatafora JW. The genome of tolypocladium inflatum: evolution, organization, and expression of the cyclosporin biosynthetic gene cluster. PLOS Genetics. June 2013, 9 (6): e1003496. PMC 3688495

. PMID 23818858. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003496

. PMID 23818858. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003496  .

.

- ^ Xu L, Li Y, Biggins JB, Bowman BR, Verdine GL, Gloer JB, Alspaugh JA, Bills GF. Identification of cyclosporin C from Amphichorda felina using a Cryptococcus neoformans differential temperature sensitivity assay. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. March 2018, 102 (5): 2337–2350. PMC 5942556

. PMID 29396588. doi:10.1007/s00253-018-8792-0.

. PMID 29396588. doi:10.1007/s00253-018-8792-0.

- ^ di Salvo ML, Florio R, Paiardini A, Vivoli M, D'Aguanno S, Contestabile R. Alanine racemase from Tolypocladium inflatum: a key PLP-dependent enzyme in cyclosporin biosynthesis and a model of catalytic promiscuity. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics. January 2013, 529 (2): 55–65. PMID 23219598. doi:10.1016/j.abb.2012.11.011.

- ^ 48.0 48.1 48.2 Borel JF, Kis ZL, Beveridge T. The history of the discovery and development of Cyclosporin (Sandimmune). Merluzzi VJ, Adams J (编). The search for anti-inflammatory drugs case histories from concept to clinic. Boston: Birkhäuser. 1995: 27–63. ISBN 978-1-4615-9846-6. (原始内容存档于2017-11-05).

- ^ Cheng M. Hartmann Stahelin (1925-2011) and the contested history of cyclosporin A. Clinical Transplantation. 2013, 27 (3): 326–329. PMID 23331048. S2CID 39502677. doi:10.1111/ctr.12072.

- ^ Borel JF, Feurer C, Gubler HU, Stähelin H. Biological effects of cyclosporin A: a new antilymphocytic agent. Agents and Actions. July 1976, 6 (4): 468–75. PMID 8969. S2CID 2862779. doi:10.1007/bf01973261.

- ^ Rüegger A, Kuhn M, Lichti H, Loosli HR, Huguenin R, Quiquerez C, von Wartburg A. [Cyclosporin A, a Peptide Metabolite from Trichoderma polysporum (Link ex Pers.) Rifai, with a remarkable immunosuppressive activity] [Cyclosporin A, a Peptide Metabolite from Trichoderma polysporum (Link ex Pers.) Rifai, with a remarkable immunosuppressive activity]. Helvetica Chimica Acta. 1976, 59 (4): 1075–92. PMID 950308. doi:10.1002/hlca.19760590412 (德语).

- ^ Heusler K, Pletscher A. The controversial early history of cyclosporin. Swiss Medical Weekly. June 2001, 131 (21–22): 299–302. PMID 11584691. S2CID 24662504. doi:10.4414/smw.2001.09702

.

.

- ^ Calne RY, White DJ, Thiru S, Evans DB, McMaster P, Dunn DC, Craddock GN, Pentlow BD, Rolles K. Cyclosporin A in patients receiving renal allografts from cadaver donors. The Lancet. 1978, 2 (8104–5): 1323–7. PMID 82836. S2CID 10731038. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(78)91970-0.

- ^ Starzl TE, Klintmalm GB, Porter KA, Iwatsuki S, Schröter GP. Liver transplantation with use of cyclosporin a and prednisone. The New England Journal of Medicine. July 1981, 305 (5): 266–9. PMC 2772056

. PMID 7017414. doi:10.1056/NEJM198107303050507.

. PMID 7017414. doi:10.1056/NEJM198107303050507.

- ^ Kolata G. FDA speeds approval of cyclosporin. Science. September 1983, 221 (4617): 1273. Bibcode:1983Sci...221.1273K. PMID 17776314. doi:10.1126/science.221.4617.1273-a.

On 2 September (1983), the Food and Drug Administration approved cyclosporin, a new drug that suppresses the immune system.

- ^ Gottesman J. Milestones in Cardiac Care. Los Angeles Times. 1988-03-20. (原始内容存档于2017-02-26).

- ^ First Successful Pediatric Heart Transplant [ 1984-06-09]. Columbia University Medical Center, Dept. of Surgery, Cardiac Transplant Program. (原始内容存档于2017-03-01).

It [cyclosporine] gained FDA approval at the end of 1983, ...

- ^ Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products [Click on "Approval Date(s) and History]. United States Food and Drug Administration. (原始内容存档于2017-03-01).

Drug Name(s): Sandimmune (Cyclosporine), Company: Novartis, Action Date: 11/14/1983, Action Type: Approval, Submission Classification: Type 1 - New Molecular Entity, Review Priority: Priority

- ^ 59.0 59.1 59.2 Starzl, Thomas E. The Puzzle People: Memoirs Of A Transplant Surgeon. University of Pittsburgh Press. 1992. ISBN 978-0-8229-3714-2. doi:10.2307/j.ctt9qh63b.

- ^ Guidelines on the Use of International Nonproprietary Names (INNs) for Pharmaceutical Substances. World Health Organization. 1997.

To facilitate the translation and pronunciation of INN, "f" should be used instead of "ph", "t" instead of "th", "e" instead of "ae" or "oe", and "i" instead of "y"; the use of the letters "h" and "k" should be avoided.

[失效链接] - ^ The Cyclosporine Story. www.davidmoore.org.uk. January 2013 [2022-10-24]. (原始内容存档于2022-10-22).

- ^ Gibaud S, Attivi D. Microemulsions for oral administration and their therapeutic applications. Expert Opinion on Drug Delivery. August 2012, 9 (8): 937–51 [2018-03-04archive-date=2018-03-05]. PMID 22663249. S2CID 28468973. doi:10.1517/17425247.2012.694865. (原始内容存档于使用

|archiveurl=需要含有|archivedate=(帮助)). - ^ Min DI. Neoral: a microemulsion cyclosporine. Journal of Transplant Coordination. March 1996, 6 (1): 5–8. PMID 9157923. doi:10.7182/prtr.1.6.1.f04016025hh795up (不活跃 2024 -11-11).

- ^ Neoral (PDF). FDA Data Dashboard. Food and Drug Administration (FDA); Novartis. September 2009 [2022-10-24]. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2022-10-20).

- ^ Clinical trial number NCT01287078 for "Cyclosporine Inhalation Solution (CIS) in Lung Transplant and Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant Recipients for the Treatment of Bronchiolitis Obliterans" at ClinicalTrials.gov .

- ^ Trammer B, Amann A, Haltner-Ukomadu E, Tillmanns S, Keller M, Högger P. Comparative permeability and diffusion kinetics of cyclosporine A liposomes and propylene glycol solution from human lung tissue into human blood ex vivo. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics. November 2008, 70 (3): 758–64. PMID 18656538. doi:10.1016/j.ejpb.2008.07.001.

- ^ Sullivan PG, Thompson M, Scheff SW. Continuous infusion of cyclosporin A postinjury significantly ameliorates cortical damage following traumatic brain injury. Experimental Neurology. February 2000, 161 (2): 631–7. PMID 10686082. S2CID 25190221. doi:10.1006/exnr.1999.7282.

- ^ Mende U, Kagen A, Cohen A, Aramburu J, Schoen FJ, Neer EJ. Transient cardiac expression of constitutively active Galphaq leads to hypertrophy and dilated cardiomyopathy by calcineurin-dependent and independent pathways. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America //www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC24952

|PMC=缺少标题 (帮助). November 1998, 95 (23): 13893–8. Bibcode:1998PNAS...9513893M. PMC 24952 . PMID 9811897. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.23.13893

. PMID 9811897. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.23.13893  .

.

- ^ Archer TM, Boothe DM, Langston VC, Fellman CL, Lunsford KV, Mackin AJ. Oral cyclosporine treatment in dogs: a review of the literature. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine. 2014, 28 (1): 1–20. PMC 4895546

. PMID 24341787. doi:10.1111/jvim.12265.

. PMID 24341787. doi:10.1111/jvim.12265.

- ^ Palmeiro BS. Cyclosporine in veterinary dermatology. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice. January 2013, 43 (1): 153–71. PMID 23182330. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2012.09.007.