齿状回

| 齿状回 | |

|---|---|

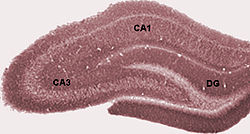

海马体区域图。 DG代表齿状回。 | |

脑桥正前方的大脑冠状切面。 (“齿状回”的标签在底部中央。) | |

| 基本信息 | |

| 属于 | 颞叶 |

| 动脉 | 大脑后动脉 前脉络丛动脉 |

| 标识字符 | |

| 拉丁文 | gyrus dentatus |

| MeSH | D018891 |

| NeuroNames | 179 |

| NeuroLex ID | birnlex_1178 |

| TA98 | A14.1.09.237、A14.1.09.339 |

| TA2 | 5521 |

| FMA | FMA:61922 |

| 格雷氏 | p.827 |

| 《神经解剖学术语》 [在维基数据上编辑] | |

齿状回(英文:Dentate gyrus,缩写:DG)是大脑颞叶海马结构的一部分,其中还包括海马体和下托。齿状回是海马体三突触回路的一部分。它被认为有助于形成新的情节记忆、[1][2]自发探索新环境[2]和其他功能。[3]

值得注意的是,它是已知在许多哺乳动物(从啮齿目到灵长目动物)中具有显着的成体神经发生率的少数几个大脑结构之一。[4]成体神经发生可能发生的其他部位包括脑室下区、纹状体和小脑。[5]然而,成人齿状回中是否存在显着的神经发生一直是一个有争议的问题。[6][7]2019年的证据表明,成体神经发生确实发生在脑室下区和齿状回的颗粒层下区。[8][9]

结构

[编辑]

齿状回与海马体一样,由三个不同的原皮层组成:外层是分子层、中间层是颗粒细胞层、内层是多态层。[10]组成海马体的原皮层:外层是分子层,中间层是锥体层、内层是定向层。多态层也是齿状回的门(CA4,海马体和齿状回的交界处)。[11][12]

颗粒层位于上面的分子层和下面的多态层(门)之间。[13]颗粒层的颗粒细胞投射出称为苔藓状纤维的轴突,在CA3锥体神经元的树突上形成兴奋性突触。颗粒细胞以层压的方式紧密堆积在一起,抑制了神经元的兴奋。[14]

颗粒细胞的一些基底树突向上弯曲进入分子层。而大多数基底树突则进入门。这些门树突更短更细,侧枝也更少。[15]

门中的第二种兴奋性细胞类型是苔藓细胞。[11]它沿隔颞轴广泛投射其轴突(从隔区到颞叶),同侧投射跳过细胞体附近的前1-2毫米[16]。通过随机化它们的细胞分布来准备CA3中的一组细胞组合以用于数据检索的作用。[17]

在门和颗粒细胞层之间是一个称为颗粒层下区的区域,是成体神经发生的部位。[13]

齿状回前内侧的延续称为齿状回尾部,或Band of Giacomini。大部分齿状回没有暴露在脑表面,但齿状回尾部却暴露在表面,是钩回下表面的重要标志。[18]

三突触回路

[编辑]三突触回路由内嗅皮II层的兴奋性细胞(主要是星状细胞)组成,通过穿缘通路投射到齿状回的颗粒细胞层。[19][20]齿状回不接收来自其他皮层结构的直接输入。[21]穿缘通路分为内侧穿缘通路和外侧穿缘通路,分别产生于内嗅皮质的内侧和外侧。内侧穿缘通路突触到颗粒细胞的近端树突区域,而外侧穿缘通路突触到颗粒细胞的远端树突。齿状回的大多数侧面视图似乎表明一个结构仅由一个实体组成,但内侧运动可能提供齿状回腹侧和背侧部分的证据。[22]称为苔藓状纤维的颗粒细胞的轴突与CA3和CA1的锥体细胞建立兴奋性突触连接。[20]

发育

[编辑]齿状回中的颗粒细胞的特点是它们在大脑发育过程中形成的时间较晚。在老鼠中,大约85%的颗粒细胞是在出生后产生的。[23]据推测,在人类中,颗粒细胞在妊娠第10.5至11周开始生成,并在妊娠中期、晚期、出生后直至成年的期间继续生成。[24][25]科学家研究了在老鼠大脑发育过程中颗粒细胞的生发来源及其迁移途径。[26]最老的颗粒细胞在海马神经上皮的特定区域产生,并在胚胎期(E)17/18左右迁移到原始齿状回,然后作为形成颗粒层中最外层的细胞沉淀。接着,齿状前体细胞移出海马神经上皮的同一区域,并保留其有丝分裂能力,侵入正在形成的齿状回的门(核心)。从这时起,这种分散的生发基质就是颗粒细胞的来源。新生成的颗粒细胞聚集在已经开始沉淀在颗粒层中的旧细胞之下。随着更多颗粒细胞的产生,层慢慢变厚,细胞根据年龄堆积,越老的越浅,越年轻的越深。[27]颗粒细胞前体保留在颗粒下区域,随着齿状回的生长逐渐变薄,但这些前体细胞保留在成年老鼠体内。这些稀疏分散的细胞不断产生颗粒细胞神经元,[28][29]增加了神经元总数。老鼠、猴子和人类的齿状回还有许多其他差异。老鼠的颗粒细胞只有顶端树突,但在猴子和人类中,许多颗粒细胞有基底树突。[30]

作用

[编辑]

齿状回被认为有助于记忆的形成,并在抑郁症中发挥作用。

海马体在学习和记忆中的作用已经研究了几十年,特别是自1950年之后。根据手术结果,一名美国男性切除了大部分海马体。[33]目前尚不清楚海马体如何促成新记忆的形成,但在该大脑区域发生了一个称为长时程增强作用(LTP)的过程。[34]LTP涉及在反复刺激后持久强化突触连接。[19]虽然齿状回显示LTP,但它也是哺乳动物大脑中为数不多的成体神经发生(新神经元的形成)发生的区域之一。一些研究假设新的记忆可以优先使用齿状回新形成的颗粒细胞,这为区分相似事件的多个实例或多次访问同一位置提供了一种潜在的机制。[35]相应地,有人提出,未成熟的新生颗粒细胞接受与来自内嗅皮层II层的轴突形成新的突触连接,通过这种方式,首先将具有适当年龄的年轻颗粒细胞中的事件关联起来,从而将特定的新事件群作为情景记忆来记忆。[36]通过在迷宫中的表现可以看出,增加的神经发生与改善啮齿动物的空间记忆有关,这一事实强化了这一概念。[37]

已知齿状回用作预处理单元。虽然CA3子域参与记忆的编码、存储和检索,但齿状回在模式分离中很重要。[20]当信息通过穿缘通路进入时,齿状回将非常相似的信息分成不同且独特的细节。[38][39]这确保了新的记忆被单独编码,而无需从先前存储的类似特征的记忆中输入,[13]并准备相关数据以存储在CA3区域中。[38]模式分离提供了将一个记忆与其他存储的记忆区分开来的能力。[40]模式分离始于齿状回。齿状回中的颗粒细胞使用竞争性学习处理感觉信息,并传递初步表示以形成位置场。[41]位置场非常具体,因为它们能够重新映射和调整发射率以响应细微的感觉信号变化。这种特异性对于模式分离至关重要,因为它可以将记忆彼此区分开来。[40]

齿状回显示出一种特定形式的神经可塑性,这是由于新形成的兴奋性颗粒细胞的持续整合所致。[13]

临床意义

[编辑]记忆

[编辑]将海马体与记忆形成联系起来的顺行性遗忘症最突出的早期病例之一是亨利·莫莱森(匿名称为患者H.M.,直到2008年去世)。[34]他的癫痫症通过手术切除海马体(左右半球各有自己的海马体)以及一些周围组织得到治疗。这种有针对性的脑组织切除使莫莱森先生无法形成新的记忆。从那时起,海马体就被认为对记忆形成至关重要,尽管所涉及的过程尚不清楚。[34]

压力和抑郁

[编辑]齿状回也可能在压力和抑郁中发挥作用。例如在老鼠中,已发现神经发生随着抗抑郁药的长期治疗而增加。[42]压力的生理效应,通常表现为皮质醇等糖皮质激素的释放,以及交感神经系统(自主神经系统的一个分支)的激活,已被证明可抑制灵长类动物的神经发生过程。[43]已知内源性和外源性糖皮质激素都会导致精神病和抑郁症,[44]这意味着齿状回的神经发生可能在调节压力和抑郁症状方面发挥重要作用。[45]

血糖

[编辑]哥伦比亚大学欧文医学中心研究人员的研究表明,血糖调节不佳会对齿状回产生有害影响,从而导致记忆力下降。[46]

其他

[编辑]在老鼠身上看到的一些证据表明,齿状回的神经发生随着有氧运动而增加。[47]几项实验表明,当成年啮齿动物暴露于丰富的环境中时,神经发生(神经组织的发育)通常会增加。[48][49]

突触相关蛋白DLG1(齿状回中的一种支架蛋白质)的突变可能在精神分裂症的易感性中起作用。[50][51]

空间行为

[编辑]有研究表明,在大约90%的齿状回细胞被破坏后,老鼠在穿过之前通过的迷宫时遇到了极大的困难。经过多次测试它们是否可以学习迷宫,结果显示老鼠不能通过迷宫,表明它们的工作记忆严重受损。老鼠在放置策略方面也遇到了麻烦,因为它们无法将关于迷宫的学习信息整合到它们的工作记忆中,因此,在后来的试验中穿过同一个迷宫时,它们无法记住它。每次老鼠进入迷宫,老鼠的表现就好像它第一次看到迷宫一样。[52]

参考文献

[编辑]- ^ Amaral, David G.; Scharfman, Helen E.; Lavenex, Pierre. The dentate gyrus: Fundamental neuroanatomical organization (Dentate gyrus for dummies). The Dentate Gyrus: A Comprehensive Guide to Structure, Function, and Clinical Implications. Progress in Brain Research 163. 2007: 3–790. ISBN 9780444530158. PMC 2492885

. PMID 17765709. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63001-5.

. PMID 17765709. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63001-5.

- ^ 2.0 2.1 Saab BJ, Georgiou J, Nath A, Lee FJ, Wang M, Michalon A, Liu F, Mansuy IM, Roder JC. NCS-1 in the dentate gyrus promotes exploration, synaptic plasticity, and rapid acquisition of spatial memory.. Neuron. 2009, 63 (5): 643–56. PMID 19755107. S2CID 5321020. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2009.08.014

.

.

- ^ Scharfman, Helen E. (编). The Dentate Gyrus: A Comprehensive Guide to Structure, Function, and Clinical Implications. Elsevier. 2011 [2022-11-19]. ISBN 978-0-08-055175-3. (原始内容存档于2022-11-19).[页码请求]

- ^ Cameron HA, McKay RD. Adult neurogenesis produces a large pool of new granule cells in the dentate gyrus. J. Comp. Neurol. July 2001, 435 (4): 406–17 [2022-11-19]. PMID 11406822. S2CID 15254735. doi:10.1002/cne.1040. (原始内容存档于2021-08-31).

- ^ Ponti G, Peretto P, Bonfanti L. Genesis of neuronal and glial progenitors in the cerebellar cortex of peripuberal and adult rabbits. PLOS ONE. 2008, 3 (6): e2366. Bibcode:2008PLoSO...3.2366P. PMC 2396292

. PMID 18523645. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002366

. PMID 18523645. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0002366  .

.

- ^ Sorrells SF, Paredes MF, Cebrian-Silla A, Sandoval K, Qi D, Kelley KW, et al. Human hippocampal neurogenesis drops sharply in children to undetectable levels in adults. Nature. March 2018, 555 (7696): 377–381. Bibcode:2018Natur.555..377S. PMC 6179355

. PMID 29513649. doi:10.1038/nature25975.

. PMID 29513649. doi:10.1038/nature25975.

- ^ Boldrini M, Fulmore CA, Tartt AN, Simeon LR, Pavlova I, Poposka V, et al. Human Hippocampal Neurogenesis Persists throughout Aging. Cell Stem Cell. April 2018, 22 (4): 589–599.e5. PMC 5957089

. PMID 29625071. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2018.03.015.

. PMID 29625071. doi:10.1016/j.stem.2018.03.015.

- ^ Abbott, Louise C.; Nigussie, Fikru. Adult neurogenesis in the mammalian dentate gyrus. Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia. January 2020, 49 (1): 3–16. PMID 31568602. doi:10.1111/ahe.12496

.

.

- ^ Tuncdemir, Sebnem Nur; Lacefield, Clay Orion; Hen, Rene. Contributions of adult neurogenesis to dentate gyrus network activity and computations. Behavioural Brain Research. November 2019, 374: 112112. PMC 6724741

. PMID 31377252. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2019.112112.

. PMID 31377252. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2019.112112.

- ^ Treves, A.; Tashiro, A.; Witter, M.P.; Moser, E.I. What is the mammalian dentate gyrus good for?. Neuroscience. July 2008, 154 (4): 1155–1172. PMID 18554812. S2CID 14710031. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.04.073.

- ^ 11.0 11.1 Scharfman, Helen E. The enigmatic mossy cell of the dentate gyrus. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. September 2016, 17 (9): 562–575. PMC 5369357

. PMID 27466143. doi:10.1038/nrn.2016.87.

. PMID 27466143. doi:10.1038/nrn.2016.87.

- ^ Haines, D; Mihailoff, G. Fundamental neuroscience for basic and clinical applications Fifth. 2018: 461. ISBN 9780323396325.

- ^ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 Tuncdemir, Sebnem Nur; Lacefield, Clay Orion; Hen, Rene. Contributions of adult neurogenesis to dentate gyrus network activity and computations. Behavioural Brain Research. November 2019, 374: 112112. PMC 6724741

. PMID 31377252. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2019.112112.

. PMID 31377252. doi:10.1016/j.bbr.2019.112112.

- ^ Nadler, J. Victor. The recurrent mossy fiber pathway of the epileptic brain. Neurochemical Research. 2003, 28 (11): 1649–1658. PMID 14584819. S2CID 2566342. doi:10.1023/a:1026004904199.

- ^ Seress, László; Mrzljak, Ladislav. Basal dendrites of granule cells are normal features of the fetal and adult dentate gyrus of both monkey and human hippocampal formations. Brain Research. March 1987, 405 (1): 169–174. PMID 3567591. S2CID 23358962. doi:10.1016/0006-8993(87)91003-1.

- ^ Amaral DG, Witter MP. The three-dimensional organization of the hippocampal formation: a review of anatomical data. Neuroscience. 1989, 31 (3): 571–591. PMID 2687721. S2CID 28430607. doi:10.1016/0306-4522(89)90424-7.

- ^ Legéndy CR. On the 'data stirring' role of the dentate gyrus of the hippocampus. Reviews in the Neurosciences. 2017, 28 (6): 599–615. PMID 28593904. S2CID 3716652. doi:10.1515/revneuro-2016-0080.

- ^ Elgendy, Azza. Band of Giacomini | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org. Radiopaedia. [2019-10-17]. (原始内容存档于2021-05-26).

- ^ 19.0 19.1 Blumenfeld, Hal. Neuroanatomy through clinical cases 2nd. Sunderland, Mass.: Sinauer Associates. 2010. ISBN 978-0878936137.

- ^ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Senzai, Yuta. Function of local circuits in the hippocampal dentate gyrus-CA3 system. Neuroscience Research. March 2019, 140: 43–52. PMID 30408501. S2CID 53220907. doi:10.1016/j.neures.2018.11.003.

- ^ Nolte, John. The Human Brain: An Introduction to Its Functional Neuroanatomy fifth. 2002: 570–573.

- ^ Rachel A. Dalley; Lydia L. Ng; Angela L. Guillozet-Bongaarts. Dentate Gyrus. Nature Precedings. 2008. doi:10.1038/npre.2008.2095.1

.

.

- ^ Bayer SA, Altman J. Hippocampal development in the rat: cytogenesis and morphogenesis examined with autoradiography and low-level X-irradiation. J. Comp. Neurol. November 1974, 158 (1): 55–79. PMID 4430737. S2CID 17968282. doi:10.1002/cne.901580105.

- ^ Bayer SA, Altman J. The Human Brain During The Early First Trimester. 5 Atlas of Human Central Nervous System Development. 2008. Appendix, p. 497.

- ^ Eriksson PS, Perfilieva E, Björk-Eriksson T, et al. Neurogenesis in the adult human hippocampus. Nat. Med. November 1998, 4 (11): 1313–7. PMID 9809557. doi:10.1038/3305

.

.

- ^ Altman J, Bayer SA. Migration and distribution of two populations of hippocampal granule cell precursors during the perinatal and postnatal periods. J. Comp. Neurol. November 1990, 301 (3): 365–81. PMID 2262596. S2CID 7425653. doi:10.1002/cne.903010304.

- ^ Angevine JB. Time of neuron origin in the hippocampal region. An autoradiographic study in the mouse. Exp Neurol Suppl. October 1965, (Suppl 2): Suppl 2:1–70. PMID 5838955.

- ^ Bayer SA, Yackel JW, Puri PS. Neurons in the rat dentate gyrus granular layer substantially increase during juvenile and adult life. Science. May 1982, 216 (4548): 890–2. Bibcode:1982Sci...216..890B. PMID 7079742. doi:10.1126/science.7079742.

- ^ Bayer SA. Changes in the total number of dentate granule cells in juvenile and adult rats: a correlated volumetric and 3H-thymidine autoradiographic study. Exp Brain Res. 1982, 46 (3): 315–23. PMID 7095040. S2CID 18663323. doi:10.1007/bf00238626.

- ^ Amaral, David G.; Scharfman, Helen E.; Lavenex, Pierre. The dentate gyrus: Fundamental neuroanatomical organization (Dentate gyrus for dummies). The Dentate Gyrus: A Comprehensive Guide to Structure, Function, and Clinical Implications. Progress in Brain Research 163. 2007: 3–790. ISBN 9780444530158. PMC 2492885

. PMID 17765709. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63001-5.

. PMID 17765709. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63001-5.

- ^ Oomen, Charlotte A.; Girardi, Carlos E. N.; Cahyadi, Rudy; Verbeek, Eva C.; Krugers, Harm; Joëls, Marian; Lucassen, Paul J. Opposite Effects of Early Maternal Deprivation on Neurogenesis in Male versus Female Rats. PLOS ONE. 2009-01-29, 4 (1): e3675. Bibcode:2009PLoSO...4.3675O. PMC 2629844

. PMID 19180242. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003675

. PMID 19180242. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0003675  .

.

- ^ Faiz M, Acarin L, Castellano B, Gonzalez B. Proliferation dynamics of germinative zone cells in the intact and excitotoxically lesioned postnatal rat brain. BMC Neurosci. 2005, 6 (1): 26. PMC 1087489

. PMID 15826306. doi:10.1186/1471-2202-6-26.

. PMID 15826306. doi:10.1186/1471-2202-6-26.

- ^ Benedict Carey. H. M., an Unforgettable Amnesiac, Dies at 82. The New York Times. 2008-12-04 [2008-12-05]. (原始内容存档于2018-06-13).

In 1953, he underwent an experimental brain operation in Hartford to correct a seizure disorder, only to emerge from it fundamentally and irreparably changed. He developed a syndrome neurologists call profound amnesia. He had lost the ability to form new declarative memories.

- ^ 34.0 34.1 34.2 Kandel ER, Schwartz J, Jessell T, Siegelbaum S, Hudspeth AJ. Principles of neural science 5th. McGraw Hill Professional. 2013. ISBN 978-0-07-139011-8.

- ^ Nakashiba T, Cushman JD, Pelkey KA, Renaudineau S, Buhl DL, McHugh TJ, et al. Young dentate granule cells mediate pattern separation, whereas old granule cells facilitate pattern completion. Cell. March 2012, 149 (1): 188–201. PMC 3319279

. PMID 22365813. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.046.

. PMID 22365813. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.046.

- ^ Kovács KA. Episodic Memories: How do the Hippocampus and the Entorhinal Ring Attractors Cooperate to Create Them?. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience. September 2020, 14: 68. PMC 7511719

. PMID 33013334. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2020.559186

. PMID 33013334. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2020.559186  .

.

- ^ Bliss RM. "Food and the Aging Mind". First in a Series: Nutrition and Brain Function. USDA. USDA.gov. August 2007 [2010-02-27]. (原始内容存档于2021-02-12).

- ^ 38.0 38.1 Jonas, Peter; Lisman, John. Structure, function, and plasticity of hippocampal dentate gyrus microcircuits. Frontiers in Neural Circuits. 2014-09-10, 8: 107. PMC 4159971

. PMID 25309334. doi:10.3389/fncir.2014.00107

. PMID 25309334. doi:10.3389/fncir.2014.00107  .

.

- ^ Lamothe-Molina, Paul J.; Franzelin, Andreas; Auksutat, Lea; Laprell, Laura; Alhbeck, Joachim; Kneussel, Matthias; Engel, Andreas K.; Morellini, Fabio; Oertner, Thomas G. cFos ensembles in the dentate gyrus rapidly segregate over time and do not form a stable map of space (PDF). 2020-08-31 [2022-11-22]. S2CID 221510080. doi:10.1101/2020.08.29.273391. (原始内容存档 (PDF)于2022-11-22).

- ^ 40.0 40.1 Moser, Edvard I.; Kropff, Emilio; Moser, May-Britt. Place Cells, Grid Cells, and the Brain's Spatial Representation System. Annual Review of Neuroscience. 2008-07-01, 31 (1): 69–89. PMID 18284371. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.061307.090723.

- ^ Rolls, Edmund T. The mechanisms for pattern completion and pattern separation in the hippocampus. Frontiers in Systems Neuroscience. 2013, 7: 74. PMC 3812781

. PMID 24198767. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2013.00074

. PMID 24198767. doi:10.3389/fnsys.2013.00074  .

.

- ^ Malberg JE, Eisch AJ, Nestler EJ, Duman RS. Chronic antidepressant treatment increases neurogenesis in adult rat hippocampus. J. Neurosci. December 2000, 20 (24): 9104–10. PMC 6773038

. PMID 11124987. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09104.2000.

. PMID 11124987. doi:10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-24-09104.2000.

- ^ Gould E, Tanapat P, McEwen BS, Flügge G, Fuchs E. Proliferation of granule cell precursors in the dentate gyrus of adult monkeys is diminished by stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. March 1998, 95 (6): 3168–71. Bibcode:1998PNAS...95.3168G. PMC 19713

. PMID 9501234. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.6.3168

. PMID 9501234. doi:10.1073/pnas.95.6.3168  .

.

- ^ Jacobs BL, van Praag H, Gage FH. Adult brain neurogenesis and psychiatry: a novel theory of depression. Mol. Psychiatry. May 2000, 5 (3): 262–9. PMID 10889528. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4000712

.

.

- ^ Surget A, Tanti A, Leonardo ED, Laugeray A, Rainer Q, Touma C, Palme R, Griebel G, Ibarguen-Vargas Y, Hen R, Belzung C. Antidepressants recruit new neurons to improve stress response regulation. Mol. Psychiatry. December 2011, 16 (12): 1177–88. PMC 3223314

. PMID 21537331. doi:10.1038/mp.2011.48.

. PMID 21537331. doi:10.1038/mp.2011.48.

- ^ Blood Sugar Control Linked to Memory Decline, Study Says. The New York Times. 2009-01-01 [2011-03-13]. (原始内容存档于2021-02-28).

- ^ Praag, H. Running increases cell proliferation and neurogenesis in the adult mouse dentate gyrus. Nature Neuroscience. 1999, 2 (3): 266–270. PMID 10195220. S2CID 7170664. doi:10.1038/6368.

- ^ Kempermann G, Kuhn HG, Gage FH. More hippocampal neurons in adult mice living in an enriched environment. Nature. April 1997, 386 (6624): 493–5. Bibcode:1997Natur.386..493K. PMID 9087407. S2CID 4281128. doi:10.1038/386493a0.

- ^ Eadie BD, Redila VA, Christie BR. Voluntary exercise alters the cytoarchitecture of the adult dentate gyrus by increasing cellular proliferation, dendritic complexity, and spine density. J. Comp. Neurol. May 2005, 486 (1): 39–47. PMID 15834963. S2CID 8386870. doi:10.1002/cne.20493. hdl:2429/15467

.

.

- ^ Boccitto M, Doshi S, Newton IP, Nathke I, Neve R, Dong F, Mao Y, Zhai J, Zhang L, Kalb R. Opposing actions of the synapse-associated protein of 97-kDa molecular weight (SAP97) and Disrupted in Schizophrenia 1 (DISC1) on Wnt/β-catenin signaling. Neuroscience. June 2016, 326: 22–30. PMC 4853273

. PMID 27026592. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.03.048.

. PMID 27026592. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.03.048.

- ^ Kay, Yuni; Tsan, Linda; Davis, Elizabeth A.; Tian, Chen; Décarie-Spain, Léa; Sadybekov, Anastasiia; Pushkin, Anna N.; Katritch, Vsevolod; Kanoski, Scott E.; Herring, Bruce E. Schizophrenia-associated SAP97 mutations increase glutamatergic synapse strength in the dentate gyrus and impair contextual episodic memory in rats. Nature Communications. December 2022, 13 (1): 798. PMC 8831576

. PMID 35145085. S2CID 246704130. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-28430-5

. PMID 35145085. S2CID 246704130. doi:10.1038/s41467-022-28430-5  .

.

- ^ Xavier GF, Costa VC. Dentate gyrus and spatial behaviour. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. August 2009, 33 (5): 762–73. PMID 19375476. S2CID 1115081. doi:10.1016/j.pnpbp.2009.03.036

.

.

外部链接

[编辑]- Slide at psycheducation.org

- Stained brain slice images which include the "Dentate gyrus" at the BrainMaps project

- McHugh TJ. Dentate Gyrus NMDA Receptors Mediate Rapid Pattern Separation in the Hippocampal Network. Science. 2007, 317 (5834): 94–99. Bibcode:2007Sci...317...94M. PMID 17556551. S2CID 18548. doi:10.1126/science.1140263. - The source of déjà vu

- NIF Search - Dentate Gyrus via the Neuroscience Information Framework

- See Altman and Bayer's work on dentate gyrus development and adult neurogenesis (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- Amaral, David G.; Scharfman, Helen E.; Lavenex, Pierre. The dentate gyrus: Fundamental neuroanatomical organization (Dentate gyrus for dummies). The Dentate Gyrus: A Comprehensive Guide to Structure, Function, and Clinical Implications. Progress in Brain Research 163. 2007: 3–790. ISBN 9780444530158. PMC 2492885

. PMID 17765709. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63001-5.

. PMID 17765709. doi:10.1016/S0079-6123(07)63001-5.